Terror in Latin America and the Caribbean

W.T. WHITNEY Jr.

[C]uban national hero José Martí referred to land lying between the Rio Grande River and the Straits of Magellan as “Our America.” In an essay with that title published in 1892, Martí evoked the Rio Grande boundary as a divide between peoples with their own history, culture and future and an industrializing, crass civilization to the north promising no good.

sponsored assassination plots; and Cuban exiles and CIA assets Luis Posada and Orlando Bosch. Posada and Bosch headed CORU, an organization carrying out murders at the behest of Southern Cone regimes.

On October 6, 1976, a Cuban airliner in flight off Barbados went down. Posada and Bosch had arranged for a bomb explosion. All 73 passengers and crew died. At the time Posada headed Venezuela’s DISIP intelligence agency under CIA auspices. The two criminals found sanctuary in Miami. (See Appendix, with the New York Times obit on Bosch, whom the prominent propaganda organ for capitalism, calls a terrorist, too.—Eds)

On September 12, 1998, the Miami FBI arrested Cuban agents Gerardo Hernández, Antonio Guerrero, Ramón Labañino, Fernando González, and René González. Known since as the Cuban Five, they had been monitoring and reporting on private paramilitary groups in Florida well known for launching terror attacks against Cuba. A biased trial and cruel sentences followed.

On September 11, 2001, an assault from the air collapsed buildings in the United States and killed 2,977 people. President George W. Bust soon told a joint session of Congress that, “We will pursue nations that provide aid or safe haven to terrorism. Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.”

In fact, the U.S. government itself had already joined “with the terrorists” in Our America. As with earlier interventions, it did so to stop social revolution. U.S. hypocrisy was obvious: official statements expressed horror and threatened retribution, yet victims in Our America already knew the pain of terrorism at U.S. hands.

Anti-communism had served as pretext for foreign interventions. But that rationale made little sense after socialism disappeared in Russia and Eastern Europe in 1990-1992, and “victory over communism” was proclaimed. The attacks on September 11, 2001 were useful for supplying a new catch-all justification. Henceforth targeted enemies were called “terrorists.”

From 1964 on, for example, the reason for U.S. government backing for Colombia, at war with the Marxist-oriented Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), morphed from anti-communism, to drug trafficking, to war against terror.

In Paraguay the United States operated an air base, deployed soldiers – oddly, on “medical missions” – and in early 2014 set up an “Emergency Operations Center” under Southern Command auspices. Its location in San Pedro Department is close to drug-trafficking Ciudad del Este, allegedly a “base for Islamic terrorist funding.” The Marxist-oriented Paraguayan People’s Army, “a group designated as terrorist,” operates nearby.

The U.S. State Department condemns Cuba for its “support for acts of international terrorism.” That designation became a tool to rationalize bullying of Cuba. Paradoxically enough, Cuba, accused of terror, still must deal with the threat of terror from the United States. In May 2014 authorities there arrested four newly arrived Miami-area residents allegedly with terror on their minds.

The case of the Cuban Five defenders against terrorism highlighted the notion of “good terrorists” and “bad terrorists.” Apparently for U.S. prosecutors the violent thugs whom the Five were watching were acceptable terrorists, no less so than U.S. agents scheming in Guatemala and Chile.

The far-seeing José Martí denounced U.S. annexationist longings for Cuba and anticipated U.S. punishment for Cuban independence. He had a remedy: nations of Our America would come together in solidarity and mutual support. Now, long after Martí’s battlefield death in Cuba’s Second War for Independence, regional integration is advancing. Alliances have proliferated.

On September 18, 2014, Panamanian Foreign Minister Isabel de Saint Malo announced Cuba would be invited to the seventh “Summit of the Americas,” organized by the Organization of American States (OAS) and to be hosted by Panama in April 2015.

The U.S. government established the OAS in 1948 as a cold-war tool. In accordance with that mission, the OAS expelled revolutionary Cuba in 1962. Now rebellion within OAS over Cuba is big news; exclusion of Cuba had epitomized its reason for being. Maybe these new dynamics will discourage U. S. terror plans for the region.

But not necessarily: presently the U.S. empire is up against the force of Marti’s good idea. But Martí, sympathetic to working people, to African-descended peoples, never let go of the notion that the interests of the poor and marginalized were shared among all socio-economic classes across the nation he hoped to build. He was weak on conflict between two great social classes. The rich and powerful in Our America of course have ties, real or imagined, to the capitalist giant in the north.

By contrast, working people feel safer with each other, whether at home or across international borders, than they do with big operators. Workers in the United States know that whatever serves globalized capitalist systems – here exploitation and domination in Our America – strengthens exploiters at home and is not good for them. It makes sense for them to join struggles of working and marginalized peoples there as their own. U.S. workers would take collective action to block U.S. sponsorship of militarization and of terror regimes.

They would be making good on a rudimentary, easily-understood prescription from revolutionary struggles of 19th century Europe: “Workers of the World Unite.” Ever since, the prospect of worker unity has terrified those in charge.

W.T. Whitney Jr. is a retired pediatrician and political journalist living in Maine.

APPENDIX

Even the New York Times admitted Orlando Bosch and his associates were unreconstructed terrorists, but —surprisingly!—American courts never managed to really make him pay for his crimes.

Orlando Bosch, Cuban Exile, Dies at 84

Bosch in 1965 (UPI)

[O]rlando Bosch, a Cuban-American pediatrician and militant Cuban exile leader who was accused, and then acquitted, of masterminding the 1976 bombing of a Cuban airliner in which 73 people were killed, died Wednesday in Miami. He was 84.

His family announced the death. He had been hospitalized with a number of illnesses.

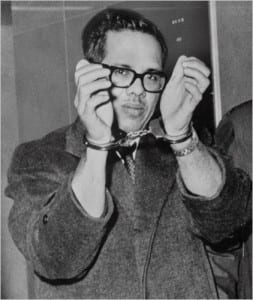

Mr. Bosch became a lightning rod in the Cuban-exile world. His supporters called him a hero, holding rallies for him and lobbying to name a Miami expressway after him. Richard L. Thornburgh, when he was the United States attorney general under the first President George Bush, called him “an unreformed terrorist.”

Mr. Bosch maintained that he had fought a “just war” against Fidel Castro — whom he called a “a monster” — often with support by the American government.

In the airliner bombing, the plane had left Barbados for Jamaica and exploded, killing everyone on board. Four people were arrested, three of them Venezuelan residents.

Tried in Venezuelan courts, two of the defendants were convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison. But Mr. Bosch — who along with another exile leader, Luis Posada Carriles, was charged with masterminding the plot — was acquitted after much of the prosecution’s evidence was ruled inadmissible. Mr. Posada, who had sometimes worked for the Central Intelligence Agency, escaped to Panama before he was tried.

In a C.I.A. report that was later declassified, Mr. Posada was said to have been overheard saying, “We are going to hit a Cuban airplane” and “Orlando has the details.” And in 2006, the Federal Bureau of Investigation released a report quoting an informant in Caracas, Venezuela, as saying that one of the men who had planted the bomb called Mr. Bosch afterward with the message, “A bus with 73 dogs went off a cliff and all got killed.”

Earlier this month, Mr. Posada was acquitted in El Paso of perjury, obstruction and immigration fraud charges in connection with his return to the United States in 2005.

Though he was acquitted in the airline attack, there is little doubt that Mr. Bosch was behind other terrorist acts in the decade after the 1959 Cuban revolution. In recommending in 1989 that he be deported, the Justice Department said he had committed 30 acts of sabotage in the United States, Puerto Rico, Panama and Cuba from 1961 through 1968.

The department said he had “repeatedly expressed and demonstrated a willingness to cause indiscriminate injury and death.”

An exile group he led claimed responsibility for 11 bombing attacks against Cuban government properties.

In 1968, Mr. Bosch was convicted of using a makeshift bazooka to shell a Communist Polish freighter docked in Miami. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison. At the same time, he was convicted of sending bomb threats to the heads of state of Britain, Mexico and Spain, and received a concurrent eight-year sentence.

Mr. Bosch had earlier been arrested six times on charges of violating United States neutrality laws.

Orlando Bosch Avila was born on Aug. 18, 1926, in the village of Potrerillo, Cuba, about 150 miles east of Havana. His father was a restaurateur and his mother a teacher. He went to medical school at the University of Havana, where he was president of the student council. He worked on student issues with Mr. Castro, the law school’s delegate to the council, then cooperated with him in fighting the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista.

Mr. Bosch did his medical internship in pediatrics at the University of Toledo in Ohio starting in 1952, then returned to Cuba to practice medicine. He vaccinated children against polio and organized clandestine support for Mr. Castro. But he became disillusioned with the revolution and in June 1960, less than 18 months after Mr. Castro came to power, Mr. Bosch fled to Miami with his wife, Myriam, and four children.

He worked for a hospital in Coral Gables, Fla., bought a beat-up blue Cadillac, took a liking to the television show “Mission: Impossible” and settled into American life. But his anti-Castro passion became consuming, and he was fired for storing explosives on the hospital grounds. He was arrested on charges of towing a homemade radio-operated torpedo through traffic. Federal agents charged him and five others with trying to smuggle 18 aerial bombs out of the country.

None of the charges stuck until he was convicted of shelling the ship. Judge William O. Mehrtens of the United States District Court called his actions stupid, saying, “I cannot reasonably see any way to fight Communism in this manner.”

After being sentenced in the ship attack, Mr. Bosch was freed on parole and fled the country, violating the terms of his release.

Using numerous passports and several names, he then traveled to countries with powerful Cuban exile communities like Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica and Venezuela. Venezuela offered to send him to the United States after he was arrested for planning an explosion at the Cuban Embassy there, but the United States refused.

He spent time in Chile, where the military government gave him housing and logistical support. There, he met his second wife, Adrian Delgado. She survives him, as do six children and five grandchildren.

In June 1976, Mr. Bosch forged a new coalition of anti-Castro groups in the Dominican Republic. The group, which is believed to have committed more than 50 terrorist acts, discussed blowing up an airliner, according to the C.I.A.

Ann Louise Bardach, in her 2003 book, “Cuba Confidential,” described Mr. Bosch as “the godfather of the paramilitary groups.” In The Atlantic Monthly in 1993, she wrote that he had developed “a cultlike following” and was called “ ‘mad’ or ‘crazy,’ sometimes affectionately.”

Mr. Bosch spent 11 years in Venezuelan jails as the legal process churned on. Miami’s mayor visited him in prison, and the city’s commissioners declared an official Orlando Bosch Day.

When Mr. Bosch arrived in Miami in February 1988, however, the welcome was not warm. He was arrested for violating his parole. In June, the Justice Department ordered him deported. But legal maneuverings and political support, including that of Jeb Bush, then a Florida businessman and later the state’s governor, kept him in detention as an undesirable alien until the first President Bush, Jeb Bush’s father, overruled the deportation order in 1990.

In return, Mr. Bosch renounced the use of force, an agreement he later called “a farce.”

“They purchased the chain,” Mr. Bosch said, “but they don’t have the monkey.”