MEMORY TRENCH: The Long and Lonesome Road to Samarkand

![]()

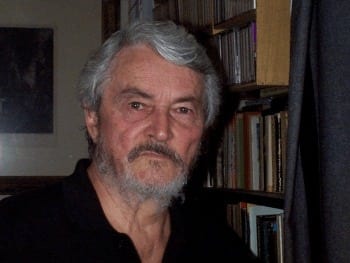

Dispatches from

Gaither Stewart

European Correspondent • Rome

Nearly two decades after Iran’s Islamic Revolution I am spending several weeks in Iran in June and July of 1995. Rinaldo, that is, the director of my newspaper himself, arranged for me to accompany a group of three Italian businessmen——an executive from the huge state-controlled Finmeccanica Group and two top engineers from its Breda Co. in Genoa, specialized in railway and metro car production—who hope to horn in on the French monopoly in contracts for rolling stock production for Tehran’s brand new metro network extending east and west and north and south over the huge capital city.

..

At the end of their high-level meetings the Italians will attend an international conference organized by the Tehran Chamber of Foreign Trade which I will cover as an envoyé special of Azione Nazionale. Many things have changed in Iran since the election of the progressive reformist Mohammad Khatami as President. Khatami, who speaks not only his native Persian, but also Arabic, English and German and served in an official capacity in Hamburg for two years, favors a free market and foreign investments, a background which has prompted his widely hailed slogan of Dialogue Among Cultures and Civilizations. The progressive Mullahs in power are aware that accelerated modernization of public transportation in hectic Tehran is a necessity for the entire Iranian economy. Since the death of Ayatollah Khomeni in 1989, Iranian progressives have exploited to the fullest Iran’s massive oil and gas production and reserves to keep up with the country’s rapidly growing population. Besides my weekly dispatches I am writing a major article about the visible modernization of the city, using my own bent for urban exploration and concentrating of the rapid development of public transportation that puts Rome to shame, while at the same time compiling my Iranian Diary. I work in my hotel in the lower city of the capital, a location I like because of the proximity to the Russian Embassy and, ironically, also the Nunciature of Vatican City, the latter, though not exactly pleased with the revolution, has come to terms with it. Despite my anti-Church attitudes, the Papal Nuncio to Iran has continually invited me as a known Vaticanist to formal dinners in the Nunciature along with the businessmen for whom I have become a volunteer interpreter from the English of their Iranian contacts to Italian. All the while I am falling in love with the country and its people and imagine myself one day spending a tour abroad there.

Today, Iran and the city of fable, Samarkand, are somehow still linked in my mind and in my romantic vision of that part of the world, a passion fueled by a chance encounter with James Elroy Flecker’s The Golden Journey to Samarkand in a comparative literary course at Brown, an incredible poem that still haunts my dreams.

And how beguile you? Death has no repose

Warmer and deeper than the Orient sand

Which hides the beauty and bright faith of those

Who make the Golden Journey to Samarkand.

And now they wait and whiten peaceably,

Those conquerors, those poets, those so fair:

They know time comes, not only you and I,

But the whole world shall whiten, here or there;

My dream is of a place of ugliness and threatening death on the one hand, and of beauty and perfection on the other. Somehow I must reach this chimeric place. Yet it is far removed and the access fraught with insuperable obstacles, a trial of courage and daring. I tramp over a dusty desert dirt road, sweating in my sport dress, then climbing, slipping and sliding, over a series of exceptionally steep hills ascents and descents that would be too much for mountain goats. I somehow pass the test of the hills and arrive at a flat desert land beyond, the gateway to which is an ugly conglomeration of shacks inhabited by dirty, emaciated and murderously mean children seemingly immune to the filth of the place which is guarded by horribly ugly vicious and hungry dogs on long chains so that passage along the narrow dirt track cutting through it is impossible. I view a picture of uncontrolled horror and evil. If I plough ahead, I am prey for the starving dogs; if I stand still I am prey for the advancing pack of ragged murderous children. I search desperately for a solution. I shout to the children if there is a taxi or a bus that can take me to the city of gold. A chorus of mad laughter echoes back to me. In my dream I drift off and dream of the joyous people in the city beyond this mean place, of people who don’t suffer or even work, joyous young men who laugh and love and sleep in beds for kings and eat red juicy melons and yellow cakes and drink long green cocktails and make love to beautiful blond girls. The ugly boys with the vicious dogs have no idea of the utopic city, but they oppose it. They are watch guards to prevent access to the city. They prefer the filth and the viciousness of their dogs. I know I can never pass through, yet behind me the first steep dusty hill is transformed, now completely vertical. And I remember Samarkand: Sweet to ride forth at evening from the wells,/When shadows pass gigantic on the sand,/And softly through the silence beat the bells/Along the Golden Road to Samarkand.

SIDEBAR

Tamerlane, or Timur, one of history’s most brutal butchers, died on February 18th, 1405. His extraordinary tomb is in Samarkand. The body was interred beneath the dome of the Gur Amir mausoleum in a steel coffin under a slab of black jade six feet long, which was then the largest piece of the stone in the world.

(Extract from my Iranian diary; a Saturday in June, 1995) Again, in the early morning, we drove through the rugged Elburz Mountains from Tehran to the Caspian Sea, then west-northwest up the Caspian coast as far as Ramsar, and then doubled back east along the shore. I wanted to head westwards for Tabriz and Azerbaijan, but the Italian businessmen were most eager to find a good fish restaurant. They entered the first place we saw. The Iranian-Armenian broker and I stood in silence at water’s edge. I was dreaming Caspian dreams and wondering about the distance to the northwest corner where the Volga River flows into this, the world’s largest enclosed body of water lined in the east by the deserts toward Samarkand. In the south by the Elburz and in the west by the great Caucasian mountains just out of our sight but whose presence we felt, range after range, peak after peak, crags and hidden streams. An impregnable fortress. The northern exposure here on the Iranian shores of the Caspian at the small town of Sulaleh is an enlightening geographical experience. We speak in the Armenian’s nearly native Russian as a result of his university studies in Yerevan, Armenia before his emigration to Iran and my Russian studies in Providence and Munich. He points to the west to indicate his present home in Tabriz, Iran. Involuntarily leaping over great expanses, I mutter the name of Samarkand. The engineer speaks instead of the North Caucasian city of Makhachkala, the capital of Russia’s Dagestan, occupied by the British during the Western intervention in the Russian civil war in 1919 before the city was occupied by the new Red Army in 1920. He speaks of the genocide of the Armenians on Mt. Ararat perpetrated by the Turks. Still dreaming Samarkand I tell him of my private Turkish language teachers, the first a Karachay from the confusing mix of peoples of the North Caucasus on the northen slopes of those great mountains. Both of their native languages are of the Turkic family. However, I am really most interested in Uzbekistan. The engineer says I would like Tabriz where the street language is Azerbaijani Turkish, nearly Anatolian. But my eyes shift back to the eastern shores in search of the country of Turkmenistan and the deserts of Uzbekistan and the road to Samarkand. I gaze across the huge Caspian Sea which looks like a full-fledged sea. Yet only puny waves roll in, even though the southern part of the sea is said to reach over one thousand meters depth. Located between Europe and Asia the Caspian retains waters from the great Volga and Ural Rivers, the latter considered the dividing line between Europe and Asia. Hard to believe that it has no outflows. All its waters converge into surrounding lakes and swamps that nature equilibrates through evaporation. There was no chance to get to those romantic sounding places one thousand kilometers to the north and its flanks spread along the sea’s northeastern shores … but I felt it there. I do not tell the Iranian of my sensation of being near the top of the world. I feel it is there, north of the Caspian, the top of the world, the center, where time perhaps stands still in which vacuum you perceive lies enormous power. The thing about this location on the Caspian is that you sense the presence of another world up there and that it has a core, the existence of which will one day surprise the world. And then, one thousand miles northwest from where we stand on the southern shores of the Caspian Sea, there is Samarkand.

Central Asia and Samarkand. Hard to imagine from the southern banks of the Caspian, much more so from the deep West, the immensity of Central Asia with its deserts and bottomless seas, soaring mountains, endless grasslands much of which borders on the Caspian Sea. After the Mongolian occupation in the 13th century, Central Asians emerged as distinct peoples. After the Russian Revolution, the whole immense area became Soviet Socialist Republics.

Today again, at home in Rome, just as that day on the banks of the Caspian Sea, I lose myself and the sense of time, feeling myself practically inside the same vast expanse as depicted in my huge world atlas. I feel the almost ungraspable immensity of Eurasia and everything in it. Departure from China in Spring and hopeful arrival in the Fall. Exotic caravanserai in the great deserts of Central Asia, of deep seas, meandering lakes, and rivers to navigate, of rugged mountains to be negotiated. .

Pre-Islamic Central Asia, I keep in mind, was an Iranian region including nomadic Iranian-speaking peoples like the Scythians and Parthians until the expansion of Turkic peoples when Central Asia became the home of those Turkic-speaking peoples of the Soviet republics. But something of the former Iranian connection must have remained: the Tadjiks and some Uzbeks speak a variety of Iranian. Close Russo-Iranian relations are no surprise; their relationship is not only geographical, but also historical and genetic. And the people speak Iranian in exotic Samarkand.

![]()

Our Senior Editor based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

Our Senior Editor based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

=SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

free • safe • invaluable