WALLS

Dispatches from

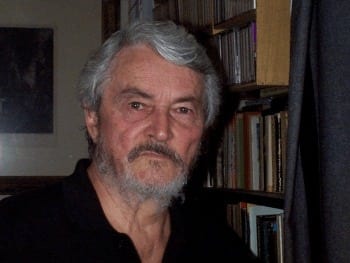

Gaither Stewart

European Correspondent • Rome

Not too long ago the international media reported that the conservative government of Hungary has projected a wall along the country’s southern border with Serbia to keep out clandestine Serbs who cross into Hungary in search of work. Some readers will recall that in 1999 the U.S. used Hungary as a base for the Serbian opposition organization, OTPOR (resistance), hailed in the West as the representative of democratic Serbia against the evil Communist dictatorship of Slobodan Milosevic, which however was financed and to some extent run by the West in an early color revolution, similar to the support for the Nazi anti-Russian group on the Maidan in Ukraine this year. Roger Cohen of the NY TIMES revealed that between 1998 and 2000 OTPOR received funds from three U.S. organizations including the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) which met with OTPOR leaders also in Budapest, Hungary. The planned Hungarian wall today prompted me to revive and refresh my previous article and a translation of a story by Jorge Borges, both about walls.

A few years ago an amusing satirical article in the Buenos Aires leftwing daily, Pagina 12, made me want to cry. In some five thousand words the Argentinean journalist José Pablo Feinmann ridiculed, among other things, the whole concept of the great wall the U.S. Bush government projected along the border with Mexico.

“What? Raise a wall. The gringos must be very afraid,” the journalist writes. “Just suppose the Wall then becomes a Goal, a Goal that attracts people from all parts, just to see if they can reach the Goal. What would be the Goal? The Goal would be to jump over the wall. Let’s just suppose that a crazy German comes with an enormous hook and says, ‘I can jump over the Wall of the Gringos.’ And suppose the Wall then retains this name: The Wall of the Gringos.”

(The journalist goes on to recall that the word Gringo calls to mind the rancor of Latin Americans, things like the Cuban Revolution and Fidel Castro and “Gringos de mierda, imperialist pigs go home,” and the Wall then becomes the symbol of burgeoning North American Fascism. There are many legends about the origin of the word Gringo—perhaps from the Green Coats of American soldiers in the Mexican-American War of 1846-48, “green coats go home” becomes “greens-go.” Argentineans called all immigrants, especially Italians, gringos. But as a rule today Gringo means Yankee, and is generally pejorative, even if North Americans in Mexico and southwards call themselves Gringos … but maybe that’s like whistling in the dark graveyard.)

MEN AND WALLS

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]alls usually express fear and have never enjoyed much success. Like the walled cities of Jericho or of Old Europe, walls have usually been defensive. They aim at keeping out the enemy. But many centuries ago barbarians easily overran the 19-kilometer Aurelian walls around Rome, today crumbling, and that I once walked in one day. These however were small walls, insignificant walls, and even though the walls of Troy resisted for ten years, most walls fell quite easily to hooks and rams and ladders. Instead the 155-kilometer Berlin Wall was intended to keep people in (or was it only that?)—and who can say what could happen in Bush’s Republic?—but anyway the Berlin Wall fell too. Even the 6,700 mile Wall of China has gradually crumbled and become a tourist attraction. And what about the Israeli Wall? For the whole Arab world, for Berliners, for many Europeans, it is forty kilometers of evil. The reality is, walls just don’t work.

The mere idea of a 700-mile wall between the USA and its neighbor Mexico is mind-boggling. The image of a globalized world in which contradictorily walls are built and bridges crumble recalls the feudal system when the lords only left their walled castles escorted by armed guards. The drama of illegal immigration was predicted to become the major issue of the XXI century. Now it is here. And political leaders have decided to look to the distant past for solutions: the Israeli wall and now the Wall of the Gringos are what they come up with.

A declaration of several years ago signed by 28 of 34 nations of the Organization of American States—of course NOT by the United States—expressed “deep concern” for such a “unilateral measure” contrary to the spirit of international understanding. Walls, it said, do not solve the problem of illegal immigration, and it urged the United States to recognize this position. Latin American leaders gathered in a summit in Uruguay condemned the idea of the Wall. Former Mexican President, Vicente Fox, a conservative, defined the idea of a wall on the Mexican border “stupid.” For Chilean President Michelle Bachelet a wall facing Mexico “damages the links of friendship in the hemisphere.”

At this point, as a change of pace: I am adding an exercise I have permitted myself, the translation of a story about walls by Jorge Luis Borges, which however had absolutely nothing to do with the Wall of the Gringos, to whose story I have added a few of my own comments.

The Wall and the Books (La Muralla y los Libros)

By Jorge Luis Borges

(translation from Spanish and comments by Gaither Stewart)

He, whose long wall the wand’ring Tartar bounds …

Dunciad, II, 76. (1)

I read, in past days, that the man who ordered the construction of the nearly infinite Wall of China was that First Emperor, Shih Huang Ti, who likewise ordered the burning of all the books before him. That the two gigantic operations—the five or six hundred leagues of stone to oppose the barbarians, the rigorous abolition of history, that is of the past—issued from one person and were in a certain sense his attributes, inexplicably satisfied me and, at the same time, disturbed me. The object of this note is to investigate the reasons for that emotion.

As fate would have it and in Borges style, I saw in a May issue of the best of the “NY Times in Italian,” the article “Walls Raised Against the Enemy, A Long History,” which cites the first such wall as Shih Huang Ti’s Wall of China, an article intended to demonstrate that they never work, not in Berlin nor in Israel nor in Baghdad. Nor will it work on the US-Mexican border, I would add. Tracing the references and my close reading of the Prologue is to elucidate to a limited degree the Borgesian world. If you try to pursue diligently all Borges’ literary pointers you have to be prepared to enter an infinite labyrinth in which one thing leads to another and then another, inexorably and without end, so that you do need the proverbial ball of string to find your way out. Though with contemporary web search engines this labyrinth is only a few clicks away, while I was clicking and longing to exit I imagined Borges instead in one of his libraries, finding, tracing and investigating such sources of inspiration by following his own instincts, pulling down tome after tome from the labyrinthine spaces filled with semi-illuminated shelves that he must have loved and hated. Creative writers can well understand him. On a similar tack Umberto Eco (The Name of the Rose) says that, “every work of art is a game played out at the worktable. Nothing is more harmful to creativity than the passion of inspiration. It’s the fable of bad romantics that fascinates bad poets and bad narrators. Art is a serious matter. Manzoni and Flaubert, Balzac and Stendhal wrote at the worktable. That means to construct, like an architect plans a building. Yet we prefer to believe that a novelist invents because he has a genius whispering into his ear.” (Well, so much for walls, even if I have digressed from the subject, I think it is clear that to me walls do not sound like a good idea at all). MAIN IMAGE: ISRAEL’S BORDER WALL =SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

![]()

Our Senior Editor based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

Our Senior Editor based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

free • safe • invaluable