Labyrinths: the left’s path to triumph is never simple

AN ARMED PEOPLE?

Roma, Spring 1999

Long before the Nibelungen mythology spread in Teutonic lands, in the ancient and isolated lands south of the Alps singular legends abounded that say a lot about how these peninsular peoples still think today … and how they dream. Etymologists explain that the Latin noun, legend, deriving from ancient Rome’s spoken Latin language, refers to ‘things to be read’. Those legends—those things to be read—chronicle human events that lie within the realm of possibility and relate miracles that could happen and are thus partially-preferably believed by all. Therefore they were handed down from generation to generation, evolving and transforming in the telling and in the passing of time. A millennium before the Nibelungen emerged, Romulus and Remus appeared on a hilly country apparently predestined to become the center of the star-shaped city of Rome. Maybe the two boys were not really suckled by a she-wolf and maybe they did not found the eternal city but nonetheless statues to them mark Rome today and their enduring legend is taught in schools and known by every Italian as something to be read. The mother of the two boys was allegedly the virgin priestess of the goddess Vespa, made pregnant by Mars, the god of war. According to the legend their fearful relatives considered the two boys ‘more than human’ and entrusted a servant to kill them. Instead the servant abandoned them by the River Tiber where they were saved by the she-wolf and fed by a woodpecker. The boys grew up as leaders of bands of shepherds, became outlaws, abducted the women of the nearby Sabine mountains, procreated and founded a people and the city of Rome. It is remarkable how legends born in different places and times are also similar: the mother of Jesus, Maria, recalls the virgin priestess of Rome; the presence of animals and shepherds mark the story of the founding of a new religion and that of an empire … an empire which itself became a new faith. Man’s molecules, though stable in number are by their nature unpredictable and maverick and rogue. They too rebel and wander, apparently lost somewhere in the DNA, then return to participate in the evolvement of new peoples and races. Similarly, man himself is unpredictable: if he takes one course he becomes a doctor of medicine and works in a clinic for the poor in an African village; if he takes another route, he might attempt to found a thousand year empire.

As a young man, my boss, friend and perhaps more, Editor-In-Chief Rinaldo Rivera, had worshipped the persistent legend of his Partisan father, a historical legend more colorful than the gray fascist times, war times, in which he had lived. Pride filled Rinaldo’s voice when he said that he couldn’t remember when his father was not a hero, who at the same time—he stressed—for him and his comrades in the Italian Resistance in WWII was also the archetype of the good man.

At the newspaper we all know that history well. When Rinaldo Rivera was born in 1924 in Reggio-Emilia, the Communist Party had just emerged from a split in the Socialist Party and joined the International. The sheet metal worker, Ferdinando Rivera, was one of the founders of the new workers party that two years later was dissolved by Mussolini, its press suppressed, and most of its leaders outlawed, exiled and jailed, some tortured and killed. Rinaldo’s father escaped from a fascist political prison in Sardinia to help organize the underground anti-fascist opposition and, during the war, the Resistenza against the dictator.

“My father was clandestine as long as I remember,” Rinaldo boasted. The entire Italian Left came to know that Ferdinando Rivera was ambushed and killed by Fascist troops in 1944 though there were conflicting claims as to where his comrades buried him; in fact many people believed the legend that he was still alive. The majority of the Communist Party accepted that a grave in the hills near Cuneo in Piemonte contained the remains of their militant leader and erected a monument in his honor there. Others however believed a mound among a group of graves in the Alps near Bormio was his burial site, where a second monument stands.

“I felt destined to take his place,” Rinaldo Rivera told me. “In World War II, I hid out on rooftops in the center of Florence to escape the draft until the day I could join the partisans in the Tuscan mountains. Because of the isolation and the loneliness I felt up there on those gray roofs among the chimney stacks I was often tempted to return to earth even though I would have rather died or would’ve tried to escape to Soviet Russia rather than serve one hour in Mussolini’s army.”

After university studies in the post-war, Rinaldo Rivera became a functionary in the press and information department of the PCI. By that time the Italian Communist Party led by Palmiro Togliatti had opted for the democratic path to Socialism. Rinaldo followed the main body of the Party. Not only was he a hero of the Resistance like his father, he was a co-author of its history. He accompanied Togliatti on missions to Moscow, and much later he accepted the break of the Italian Communist Party with the Soviet Union. While writing his one hundred-year history of social Europe, he developed theories that led to the emergence of the Euro-Communist movement of the 1980s which today he admits was an historical-ideological error. Meanwhile the son of a legend became a legend himself of the Italian and the European Left.

Stories and anecdotes about the grand old man circulate today among his newspaper staff in Rome and in his native Reggio-Emilia. ‘Here is my Beretta, my resent to you,’ Rinaldo Rivera allegedly said to a young man in Reggio in 1960 when he gave him his military pistol that he had used in the Resistance. ‘Someday you will need it.’ Though in his heart the Rinaldo of then still believed in the dream of a Communist revolution in Italy, he could never have imagined that the young man would become the chief of the Red Brigades, condemned and execrated by the official PCI for trying to realize that dream.

Over the years I’ve come to know two distinct Rinaldo Riveras. One is the esteemed writer, journalist and commentator on Italian life whom even right-wing politicians and journalists recognize as a true democrat and a great Italian. On his 75th birthday the entire nation paid its respects to him. Only extremists of Right and Left hate him for what he is. Democratic values are not empty words for the public Rinaldo Rivera. He has personally been down the path of temptation; he knows both Stalinism and Fascism from personal experience and stands like a rock in defense of European social values … but he has no faith in a free market. While we were watching TV footage from Genoa of the American President and our Premier together, he whispered that he didn’t know which of the two men he detested most.

Not so deep underneath the surface there is another Rinaldo Rivera, a Rinaldo Rivera modeled on his uncompromising father. That romantic Rinaldo Rivera dreams of the lost revolution. I began to understand that other Rinaldo one spring day when we were picnicking at Ostia Antica—Rinaldo and his wife, Lucia, Marco Maraini, a couple of other friends from the newspaper and Melissa and I. Since he prefers talking with young people he and I were sitting on an ancient wide stone in the shade apart from the others. His hair and mustache were full, his shoulders and arms still muscular. “Our world is about to change,” he said that day, squaring his shoulders and sitting as erectly as possible on our rock, assuming the tone he uses in his famous eleven a.m. editorial meetings which at seventy-five years old he still conducts. “Italy too must change dramatically because the country is on a steady downward spiral … down, down, down in its decline. Change in our country will perforce be a violent change. And your generation is going to bring about that change, Gael. All of you will face difficult choices,” he said, as if his entire past, recorded and documented, were parading before him.

“At that moment you will have to make the right choices. No more repetitions of the past when hero worship guided choices. The people back then applauded Mussolini, as their saviour. Now they applaud other populists as their heroes. We Italians always need a hero to resolve our national problems, a high commissioner, a tsar, a duce, to whom we wilfully give full powers ... and often ourselves. Why is that? First, because we do not know who we are in this great mixture of races. And also because the Republic of Italy has no real sovereignty. We are an occupied country. We have always belonged to someone else. We Italians suffer from the DID you told me about. Our people are from nowhere. Meet a young Italian abroad today and ask him where he’s from and he’s likely to say he’s not from anywhere or at the most that he is European … or perhaps a citizen of the world. But people of the older generation may still tell you the place they are from, as I say that I’m from Scandicci, Toscana. That’s my home, whether I live there or not. A Roman whose grandfather came from the Abruzzo identifies himself as an Abruzzese. A friend, also a Tuscan like me, from Pisa at the very edge of Tuscany, says he feels like an Etruscan. Confusion, you might say. Hero worship. Loss of identity. Belonging to a place with no sovereignty over itself means to belong to something uncertain, inchoate, foreign. So you spend your life looking for substitutes to which you can belong.

“One risk facing your generation is spontaneous revolution—mind you I don’t mean revolution as such. Spontaneous revolution or simply rebellion can never work. Eventually, spontaneous revolution peters out. And the vacuum that it leaves behind permits the rise of even more powerful authoritarianism and ends up reinforcing capitalism. My generation faced a choice just after the war. It was either the revolution that our fathers fought for and that I, a twenty-two-year old ex-Partisan, desired, or it was the democratic process that our leader Togliatti chose. His was a political decision. A decision for Italy. Nationalism. For a revolution then in our occupied and defeated country would have been a spontaneous uprising and would have been crushed and a pure dictatorship installed by the victorious powers. After much tribulation and self-searching I went with Togliatti.”

He stood up and walked around our rock in one of his characteristic poses—the elbow of his right arm braced in the hand of the other, his right hand under his chin. The others had fallen silent. Though he spoke softly, his words carried and were intended for all to hear: “I should warn you, Gael, that once you become infected by the idea of revolution, the revolutionary spirit remains in your guts forever. Someday you too will have to make that choice. You can choose either path. Whatever you choose though, who will be able to say that you were wrong?”

Rinaldo Rivera was not talking over my head. I understood him. He had been disillusioned that the real revolution never came about. It was in his blood.

“Why do you think we fought in the Resistance?” he asked, sitting back down beside me. “We accelerated the defeat of Fascism even though when we began the fight its end was already in sight. The sooner the better we thought, for we believed that the Resistance was in reality a warm-up for the real war—the definitive war for social justice, the beginning of the revolutionary struggle. We were ready. You have to keep in mind that back then the German model of Socialism had long since failed and we had the Soviet model before our eyes.”

I now realize that I understood then that he was speaking to me personally. He intended it as a lesson drawn from his own experience. Sometimes he lowered his voice as if wanting to confide in me alone. For a moment quiet would settle around us. Or maybe the quiet was in my head. Quiet and confusion. He had no reason for putting on intellectual airs there in Ostia Antica. Nor is it his habit to talk aimlessly. He never wastes words. Maybe I had already made my choice too: I also feel a sense of a mission in life, a mission that I must somehow complete. That it is futile to try to evade. Though most people seem to go about their daily lives unfettered by such concerns, sure of themselves, confident of what they think they believe in and therefore in their actions, some of us spend our lives trying to first understand what our mission is … then to fulfilling it. In any case Rinaldo Rivera’s thinking is not just theory. He wants me to benefit from his experience and make certain that I do not err. Yet he wants me to choose.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] few days later Rinaldo asked me to drop by his apartment on Aventine Hill the following afternoon, the implication being that it concerned something of significance and moreover, personal. In any case visits to his residence were rare and special. The few times I had been there I’d noted that the windows of his apartment were always wide open, his house bright and effulgent—reflecting, I thought rather poetically, the light in his eyes—so unlike most Italian homes of closed windows and locked doors and in marked contrast to his youthful isolation on the Florentine rooftops. He’d learned, I told myself, from his subsequent political sorrows and disappointments to search for life’s deeper joys in order to transcend those pains and to concentrate on lasting accomplishments … and, I believed, in order to leave a mark as his father had done.

We sat on a covered terrace. As usual he was dressed in jacket and tie. On the table between us lay a brown paper bag. Somewhat theatrically he opened it and took out an object wrapped in a purple felt cloth. “It’s a Luger, Gael.” He shifted the pistol reverently from hand to hand as if it were porcelain … as if he were estimating its weight. As he handed it to me, reaching through a ray of the afternoon sun, the black weapon glistened as if it were polished daily,

“I took it off the body of a German officer about my age I had just killed. The first and only time I ever killed a man right in front of me. It was a bitter moment. He didn’t have a chance to explain himself. Though it was war, I sometimes wish he could have explained his life choices ... if he’d even had choices.”

I was surprised at the Luger’s weight. I turned it over and felt its violence in my hands as I had my uncle’s rifle and again saw the squirrel I shot. I put it back on the table.

“I want you to have it,” he said, polishing it carefully with the felt, as I imagined he did often. “When the time of choice comes this pistol should be a symbol of the choice you are making. Put it away, Gael. Hide it. Bury it. But don’t forget it. When you make your choice—maybe the same choice I made—you can either put it away forever as I am doing in this moment in which I give it to you. Or, if you choose the revolutionary path then you have your first weapon ready.”

I felt his eyes upon me as I again picked up the pistol. I held it in my hands and comprehended Rinaldo’s vision of the pistol as more than a firearm. A pistol is commitment; it is symbolic of extreme unlimited commitment. A hand gun, I felt in that instant, is revolutionary. I felt awe. And fear. The fire descended into the back of my shoulder and spread to my neck and down the center of my back. On a personal level I was over-sensitive to such weapons because of the memory of my gun-loving uncle who beat up kids. I had never had any kind of firearm. I had never shot a pistol. What did I want with a pistol? Nothing at all. I had nothing to do with firearms. Nothing whatsoever. I considered the gun anti-communitarian, anti-socialist, a police kind of thing. I favor peace. An inward feeling. An emotion. And a stance. Peace and trust. Peace in myself. But what kind of peace can you feel with a pistol in your hands? You can’t just take things as they come … not everything, Gael. But still, I now understand that Rinaldo had in mind the primary battle like the battle the partisans had fought … the battle for weapons. Where were they to get them? The rifles and pistols they needed against the fascists. How was a disarmed people to find arms? A mystery. From one day to the next. They needed guns to battle the enemy. Where could they get them? Only from the enemy himself. Those who deserted from the defeated Italian army brought their hand arms with them to the macchia in our mountains. But the others, the old men and the kids too young for the army, had nothing. No way to defend themselves.

“In those times too, war times, weapons for the unarmed people came from the dead,” he said as if reading my mind, “from the Germans and the Fascists we killed.”

I began feeling something sacred about this pistol; Rinaldo transmitted that awe to me that day. But I did not feel peaceful when I held it.

The terrorists of the Red Brigades of the 1970s said they had felt the same awe when they first held a pistol. Awe for the death they could cause. Awe also for its symbolism. Perhaps many of them had earlier opposed the pistol, as a symbol of death and dominance. Most of them had never even held a pistol before they opted for the armed revolutionary struggle. And the first thing they had to do was arm themselves. They bought them here and there or other revolutionary movements helped arm them. Then quickly they learned to use their weapons.

The cocked pistol became the symbol of their revolutionary movement, eventually supported morally by some three million Italians who as a rule still do not own guns. The armed Brigadists reproduced the pistol’s legendary image on their leaflets bearing the pistol and the five-pointed star on a red background. Everybody in Italy knew the pistol and the star was the symbol of the armed struggle for Socialism-Communism. As if the pistol like the star influenced human destiny. The pistol in those leaden years became a minor deity. The star and the pistol became synonymous, a symbol that became a popular Italian legend that from time to time resurfaces to favor justice when socio-political oppression threatens. The Red Brigades were defeated but the lesson learned then was that revolutionary actions always require guns. No getting around that reality. Still, cruel capitalism controls the dissemination of arms as it likes. First let everybody have arms. Then militarize the police: gas, heavy weapons, tanks. So that rebellious people must decide. Some choose armed underground-guerilla resistance: it worked in Russia. It worked in Cuba, It worked in Nicaragua. The first actions of the Red Brigades in Italy and the Rote Armée Faktion in Germany aimed at arming themselves and shaming the useless temerity and foolhardiness of non-violent protest. “If you follow your star, you can’t fail,” Curcio once told me in an interview in his prison cell. “Like Dante and Virgil,” he said, “when at the end of their long voyage through the infernal regions, they again see the sky.” For me the star-pistol image came to reflect the sense of liberation you feel in your dreams when you escape from a closed place. My belief that the star-pistol image symbolizes sublime actions proved that I too changed just as Rinaldo Rivera had done.

While Rinaldo spoke in his quiet way as the Rome sun set that afternoon I recalled in a déja vu the same hesitation in Nullo’s voice when at the Giordano Bruno monument on Campo de’ Fiori he spoke of his relationship with Lenin and Bruno. He explained that the Leninist idea of a chain reaction of anti-capitalist revolutions stood as a certainty driving armed left-wing terrorists in Europe of the 1970s and 80s, the Red Brigades in Italy and the Red Army Faction in Germany. I had thought that though intellectually he held to Bruno, Lenin still lived in his heart. Lenin, Nullo often said, believed that workers in the developed countries would eventually disrupt capitalist war-making. To some extent the outcome of the Vietnam War had fulfilled his predictions, even though it was youth and not workers who helped most to end that capitalist war. Unfortunately, Nullo explained, brainwashed workers have remained attached to their tiny piece of the capitalist pie … too often its ally. Today, as millions of workers lose their jobs in Europe, the working class is stirring as in 1917. Riots and revolts flare up here and there. Perhaps in the beginning it will be a war among the poor, whites against the rest, natives against immigrants, homeless against landlords, but a war which inevitably will turn against the bourgeois masters of all. That uprising is not only fantasy in the USA where the war quietly rages only under the surface. That day Nullo had quoted Lenin; “As long as Capitalism and Socialism remain, we cannot live in peace. In the end one or the other will triumph. Either Socialism will triumph throughout the world or the most reactionary capitalist imperialism will win, the most savage imperialism which is out to throttle the rest of the world. That apparent imperialist triumph came to be called globalization. Today,” Nullo said, “capitalism’s victory has soured in the arrogance of power.”

A few years earlier I would have been eager to use Rinaldo’s pistol for real. Now doubts cloud my vision. In that moment on his terrace I wished he would finish speaking. But I also would have liked to feel again the same convictions I did earlier in my life. I felt extreme regret … almost shame for not recognizing and holding to my dream mission. I’m still a beginner in life, I excused myself. An innocent. My inner self trembled. And ever so briefly I felt things moving toward night’s darkness where, I knew, both more doubt and fear reside.

I turned the pistol over in my hands again and again. I closed one eye and aimed it left and right, and then again placed it on the table between us. I knew then as I have known each time I secretly take it from its cache at home and examine it that the pistol, like the falling star, also symbolizes the dark night of death. Rinaldo Rivera’s pistol is a constant reminder. So I still do not know whether I would fire into the face of my enemy as he did. The same doubt I had that day in Genoa when I aimed my camera at that killer: if my camera had been a pistol would I have shot to kill?

Often during the nineties when the vilest reactionaries of the capitalist system ruled the USA and oligarchs ran Russia, when the viciousness of the capitalist character became apparent, when the reflection of their murderous nature showed forth for all but the blind to see, I had fallen into temptation. Washington and NATO had Italy by the balls. In the South the resurrected secret Gladio army was poised for more action. Action to execute their plan of the total fascistification of Italy … of Europe. Hurry! Hurry! All good capitalists, rally around. Hurry! Crush the Left. The USSR had collapsed. Italian Communists were excluded from the government. Pariahs again. Step after step the Communist Party had degenerated into new obscurities. At the same time, neo-Fascists, anarchists, sections of the Secret Service, the Mafia, Masonic lodges, monarchists, Catholic fanatics, and an assortment of extremists pressured the soft dictatorship for a return to authoritarianism. Again I felt that the Left should also rise up. Again armed. From time to time I lift a floorboard in our pantry, take out the pistol and hold it in my hands. I hold it in two hands and point it around the room and try to imagine firing it into the face of a capitalist-imperialist pig. A loud voice shouts into my brain that it is the right thing to do. While most people are turning their backs on the real struggle and wallowing in their economic well-being I tell myself that I want to do the right thing. Inside the pistol’s reflection, I search for myself. But my doubts persist. Is it even me resisting temptation? Is the pistol the point? Is my participation the point? I can never find the words to describe my precise feelings about the direction my commitment in life should take. Feelings are so momentary. They are not the same as memory of words or people. So much more intimate, personal, that words can seldom describe them, as if they were not really part of memory. It is not easy to find the right words. Yet we need words, the right words. There are names and people and things, there is beauty and the quiet of my father, the consciousness of being alive and thinking so why not one word for a fleeting feeling? Without that word, only a kind of metaphysical exile remains. Sometimes I feel I am nearly there.

I project myself into the place of the early Red Brigadists during the Seventies. The first Brigadists. The authentic ones. I imagine them cut off from their past, cut off from their real life, their links with family, friends, Party and society. They are living in pure time, time shorn of attachments and measures and signposts and they themselves becoming legends. At first I imagined with envy that their time too was authentic. Then I wondered if they felt that their lives were only an interval and that time itself had stopped. Maybe they feared time without end. I understood that there was no place for love in their pure time. When my time arrived, when the successive Brigadists had long since lost their original ideals and had been infiltrated and turned by the intelligence services, I came to realize that since they lived outside time they had become indifferent, indifferent because they had learned that time tends to destroy everything, that ultimately everything comes to seem ephemeral.

Yet for many years they believed in the revolution. I was jealous of their

early convictions, their zeal and their courage and their freedom to make that choice. They also made me feel uneasy. Inferior. I felt cowardly when I read of the attack by the Left—of which I was a part—on the Red Brigades, so dedicated but simultaneously so lost. Intellectually—as I imagined Rinaldo Rivera—I understood that they were somehow the enemy of our democracy, such as it was. Another Left … but still, confusingly but above all, no less the enemy of capitalism. So that I still reserve a special corner for the Red Brigades in my heart. They too are present in my blood. They are one of the forces in the wheel of my life. My-enemy’s-enemy-is-my-friend thinking. Though intellectually I try to believe I was right in my choice, I feel that they were not wrong either. Their underground life reminds me of the sacred sites of the American Indians; they lived in dangerous places, the places their feet tread were lethal but sacred. For me the path of armed struggle would have been like a prolonged peak experience forever at the summit of a mountain, an orgasm without end, too intense to bear. I was on my once-in-a-lifetime emotional binge, pleasurable to the extreme. I realize now that total happiness (happiness? I sometimes detest that word.) would have been within reach if I had been capable of playing the part that I denied. Like my denial of my Isabel now of so long ago, the choice then would have been my chance for an instant of transcendence, the choice that few are capable of making.

I think the combination of Rinaldo Rivera’s influence and the image of the pistol he gave me has held me on a different course. I chose to use other weapons. Again I hid away the Luger. However, the sensation of something lost has remained. Not unlike the lost places and times of ancient Roma. I have lived between the world I accepted and the legendary world I could have chosen and I feel like a stateless refugee. I wonder if this compromise is what my real life was meant to be. Suspense, uncertainty, doubt, always hanging by a thread to the present course, living a misplaced life, and the awareness that there was something more important for me to do in life. Was I—am I—in the wrong time and place, I wonder? Am I living the wrong life?

At staff meetings I study Rinaldo Rivera’s face searching for signs that he too feels he erred, that he had betrayed his father. That he had betrayed himself. Sometimes I see a certain flash of nostalgia in his eyes and I wonder.

“Parents,” he commented to me one day concerning an article on the waning revolutionary spirit in Europe, “do not make revolutionaries. We have to hold our children in our arms, comfort them and put them to bed at night. That’s why parents favor nonviolence. Is that our best hope? I doubt it. And now society as we have known it is unraveling and desperation is spreading, and everything changes. Parents are one thing, solid, the heart of human society, but non-parents are the fighters. There are many things fathers and mothers cannot do.”

Nonetheless, I continue to feel the necessity of discovery. At times I feel I am one person living inside the body of a totally different person. I feel a need for unity. I believe Rinaldo too feels the same duality. While I was still in high school in America my father used to say I was like a zebra in my desire for heroic extravagance. He called that impulse “bourgeois individualism”. At the time I did not realize the extent of his criticism. Sometimes I wonder if Giustina’s death had not been the signal to change. I had lost Isabel, then my two-year old daughter … and with her my innocence. When I speak with Rinaldo about such metaphysical matters he never tells me what to do. Once he told me I was right, that unlike art, history never stands still. It develops. But he always adds that I should remember that “history or not, in the end we are all terribly alone.”

Though the secret Rinaldo dreams of revolutionary change, he takes a firm stand against terrorism by Europeans in Europe. He warns that it inevitably leads to civil war, foreign intervention and the end of democracy. Like the Pope and the Church he stands for survival and continuity of the remains of the Party. “I am a democrat,” he proclaims at the editorial meetings he has molded in his own image. He follows his journalists closely, permitting no deviations or dips into any ideology based on terrorist violence. Although he admired and loved the Red Brigades, they were his ideological enemy, a conclusion that still haunts me and sometimes seems as intolerable as it is contradictory.

“Once terrorism walks in, all hell unfolds,” he said in a widely quoted pronouncement. “We have to be acutely aware of our realities.” When he pronounces those words I always blush inwardly, I think out of shame for him. He has come to regard himself as a Socialist with a proud Communist heritage. Yet he still floats around the edges of the new left alignment replacing the Communist Party, occasionally darting in like a Vietcong guerrilla warrior to influence major decisions and then disappearing again, to fight another day. In day-to-day life I imitate him … but with reservations.

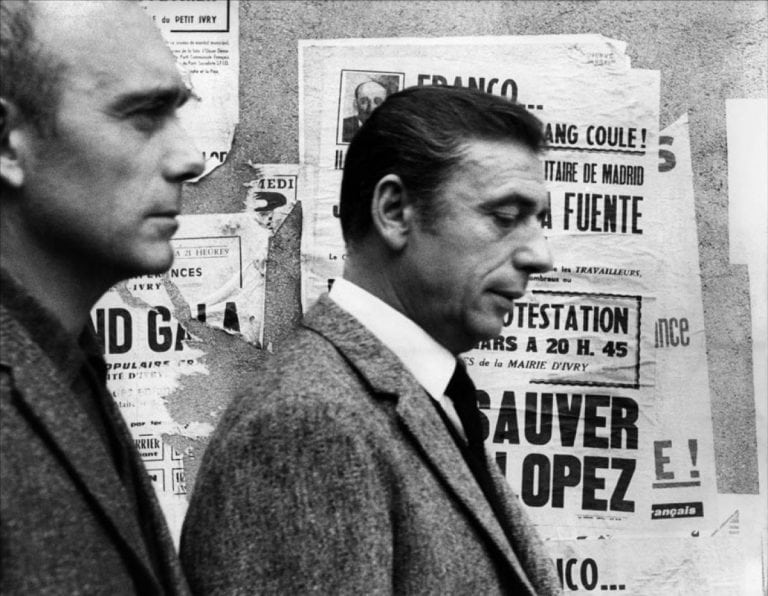

Main photo: Still from Alain Resnais' La Guerre est Finie (1966), with Yves Montand, Ingrid Thulin, Genevieve Bujold. The script was written by political activist and anti-Franquista, Jorge Semprun.

GAITHER STEWART Senior Editor, European Correspondent } Gaither Stewart serves as The Greanville Post European correspondent, Special Editor for Eastern European developments, and general literary and cultural affairs correspondent. A retired journalist, his latest book is the essay asnthology BABYLON FALLING (Punto Press, 2017). He’s also the author of several other books, including the celebrated Europe Trilogy (The Trojan Spy, Lily Pad Roll and Time of Exile), all of which have also been published by Punto Press. These are thrillers that have been compared to the best of John le Carré, focusing on the work of Western intelligence services, the stealthy strategy of tension, and the gradual encirclement of Russia, a topic of compelling relevance in our time. He makes his home in Rome, with wife Milena. Gaither can be contacted at gaithers@greanvillepost.com. His latest assignment is as Counseling Editor with the Russia Desk. His articles on TGP can be found here.

GAITHER STEWART Senior Editor, European Correspondent } Gaither Stewart serves as The Greanville Post European correspondent, Special Editor for Eastern European developments, and general literary and cultural affairs correspondent. A retired journalist, his latest book is the essay asnthology BABYLON FALLING (Punto Press, 2017). He’s also the author of several other books, including the celebrated Europe Trilogy (The Trojan Spy, Lily Pad Roll and Time of Exile), all of which have also been published by Punto Press. These are thrillers that have been compared to the best of John le Carré, focusing on the work of Western intelligence services, the stealthy strategy of tension, and the gradual encirclement of Russia, a topic of compelling relevance in our time. He makes his home in Rome, with wife Milena. Gaither can be contacted at gaithers@greanvillepost.com. His latest assignment is as Counseling Editor with the Russia Desk. His articles on TGP can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Parting shot—a word from the editors

The Best Definition of Donald Trump We Have Found