FACING STALINGRAD

FACING STALINGRAD

One battle births two contrasting cultures of memory

By Jochen Hellbeck

(With our thanks to Prof. Grover Furr, for his guidance.)

[dropcap]E[/dropcap]ach year on May 9, Russian Victory Day, surviving veterans of the 62nd Army gather at the Vassily Chuikov Primary School in northeast Moscow. At the school, named after their army commander, who defeated the Germans at Stalingrad, they listen to poems composed by schoolchildren in their honor. They tour the building’s small war museum before sitting down for a celebratory lunch in the festively decorated veterans’ room. As they toast each other with vodka or juice, they shake their heads at the destruction and losses inflicted by the war, and grow tearful remembering the dead. More toasts follow, and before long the group is carried away singing songs from the war, the sonorous baritone of Colonel General Anatoly Merezhko taking the lead. Behind the long table is an enormous poster rendition of the Berlin Reichstag in flames. After routing the Germans at Stalingrad, the 62nd Army (renamed Eighth Guards Army) marched west, through Ukraine, Belarus, and Poland, to conquer Berlin. One veteran in the room proudly points out that he inscribed his name on the walls of the German parliament building in 1945.

One Saturday each November, a group of German Stalingrad veterans travels to the town of Limburg, forty miles from Frankfurt. In an austere room of the civic center, they convene to remember their departed wartime comrades and take stock of their thinning ranks. Their reminiscences, over coffee, cake, and beer, last well into the evening. The next morning, Totensonntag, the National Day of Mourning, the veterans visit the local cemetery, where they congregate around an altar-shaped rock bearing the inscription “Stalingrad 1943.” A wreath lies on the ground, bedecked with the flags of the 22 German divisions destroyed by the Red Army between November 1942 and February 1943. Town officials hold speeches denouncing past and present wars. A reserve unit of the German army provides a guard of honor while a solo trombone player intones the sorrowful melody of the traditional German military song, “Ich hatt’ einen Kameraden” (I had a comrade).

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]ought over a duration of six months, the battle of Stalingrad marked a tidal shift in the war. Both the Nazi German and the Stalinist regimes went to extremes to force the capture, or defense, of the city that bore Stalin’s name. Amidst such intense mobilization on both sides of the front, how did enemy soldiers make sense of the war? What animated them to fight, and to fight on against formidable military odds? How did their views of themselves and the enemy evolve during this critical moment in world history? Shunning soldiers’ memoirs, because they examine war through the distorted lens of hindsight, I am instead drawn to documents from the time of the battle – military orders and propaganda leaflets, personal diaries, letters and drawings, photographs and film reels – which bear the direct imprint of the intense emotions – love, hatred, and rage – unleashed in wartime communities. State archives house few personal records from the war, and so my search for these documents led me to the reunions of German and Russian Stalingraders, and from there to the doorsteps of their homes.

The veterans willingly shared their letters and photo collections from the war, but our personal encounters made me aware of something I had initially overlooked: the enduring presence of the war in their lives, and the strikingly different ways in which Germans and Russians engage with war memories. The battle may lie almost seventy years in the past, yet traces of it are powerfully etched into the bodies, thoughts, and feelings of its survivors. I discovered a domain of the war experience that no archive could reveal. This experience pervades the veterans’ homes: it whispers through the pictures and artifacts from the war that hang on walls or are safely stowed away; it holds itself in the straight backs and courteous manners of former officers; it flares up in the scarred faces and limbs of wounded soldiers; and it lives on in the veterans’ simple gestures of sorrow and joy, pride and shame.

To fully capture the war’s complex, enduring presence required a camera in addition to a tape recorder, and my accomplished photographer friend, Emma Dodge Hanson, kindly accompanied me on my visits. In the short span of two weeks, Emma and I traveled to Moscow and a range of cities, towns, and villages in Germany, where we met nearly twenty veterans in their homes. Emma has a singular ability to record people when they are at ease with themselves, nearly oblivious to the photographer’s presence. Shot with natural light whenever possible, the pictures capture the gleam reflected in the subjects’ eyes. The richly nuanced images bring out the fine wrinkles and furrows that grow deeper as the veterans laugh, cry, or mourn. Studied together, the hours of taped testimony and the stream of photographs we captured portray the veterans residing in their recollections, as real to them as the furniture surrounding them.

![]() PLEASE download and continue reading this essay here.

PLEASE download and continue reading this essay here.

Appendix

Much has been said about Stalin’s supposedly boundless desire for adulation and his (equally putative efforts) to build a cult of personality around him. This letter, recently unearthed, from 1925 gives the lie to such assertions. Fact is, all systems of power, including so-called democracies, create circles of sycophants around the top leaders.

Stalin did not want to change Tsaritsyn to Stalingrad (1925).docx

– Istochnik 3 (2003), 54-55.

Письмо Генерального секретаря ЦК РКП(б) И. В. Сталина

секретарю Царицынского губернского комитета РКП(б) Б. П. Шеболдаеву.

25 января 1925 г.

СЕКРЕТАРЮ ЦАРИЦЫНСКОГО ГУБКОМА

тов. Ш е б о л да е в у.

«Я узнал, что Царицын хотят переименовать в Сталинград. Узнал также, что Минин добивается его переименования в Мининград. Знаю также, что Вы отложили съезд советов из-за моего неприезда, причем думаете произвести процедуру переименования в моем присутствии. Все это создает неловкое положение и для Вас, и особенно для меня. Очень прошу иметь ввиду, что:

1) Я не добивался и не добиваюсь переименования Царицына в Сталинград;

2) Дело это начато без меня и помимо меня;

3) Если так уж необходимо переименовать Царицын, назовите его Мининградом или как-нибудь иначе;

4) Если уж слишком раззвонили насчет Сталинграда и теперь трудно Вам отказаться от начатого дела, не втягивайте меня в это дело и не требуйте моего присутствия на съезде советов, – иначе может получиться впечатление, что я добиваюсь переименования;

5) Поверьте, товарищ, что я не добиваюсь ни славы, ни почета и не хотел бы, чтобы сложилось обратное впечатление»

С коммунистическим приветом

И. Сталин

РГАСПИ. Ф. 558. Оп. 11. Д. 831. Л. 44. Машинопись, подпись –факсимиле

Letter of the Secretary General of the Central Committee of the RCP (B.) I. V. Stalin

Secretary of the Tsaritsyno provincial committee of the RCP (b) B. P. Sheboldaev.

January 25, 1925

SECRETARY OF THE TSARITSYN GUBKOM

Comrade Sheboldaev.

“I have learned that some people want Tsaritsyn to be renamed Stalingrad. I have also learned that Minin is seeking to have it renamed Miningrad. I also know that you have postponed the congress of soviets because of my absence, and you are thinking of performing the renaming procedure in my presence. All this creates an awkward situation for you, and especially for me. I beg you to keep in mind that:

1) I did not seek and do not seek the renaming of Tsaritsyn to Stalingrad;

2) This matter was begun without me and apart from me;

3) If it is necessary to rename Tsaritsyn, call it Miningrad or something else;

4) If you’ve made too much noise about Stalingrad and now it’s difficult for you to abandon the case, do not drag me into this business and do not demand my presence at the congress of soviets, otherwise you may get the impression that I am seeking the renaming;

5) Believe me, comrade, that I do not seek either fame, or honor, and would not want the opposite impression to be created.

With communist greetings

I. Stalin

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

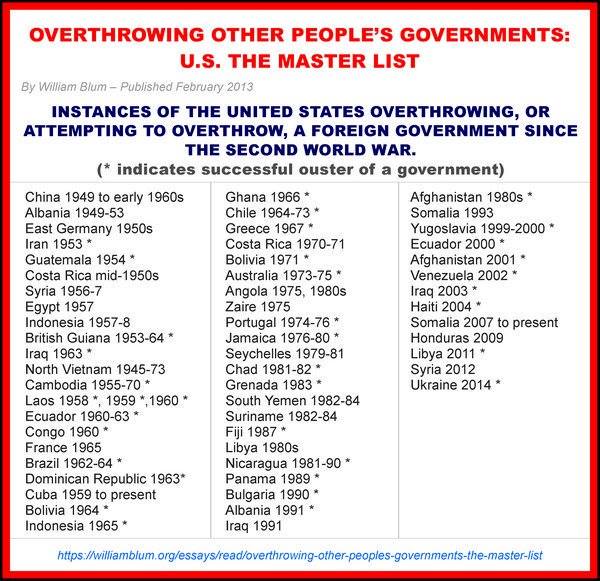

Things to ponder

While our media prostitutes, many Hollywood celebs, and politicians and opinion shapers make so much noise about the still to be demonstrated damage done by the Russkies to our nonexistent democracy, this is what the sanctimonious US government has done overseas just since the close of World War 2. And this is what we know about. Many other misdeeds are yet to be revealed or documented.

Parting shot—a word from the editors

The Best Definition of Donald Trump We Have Found

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

[premium_newsticker id=”211406″]