I mean, what are those nomads doing up over there? Riding all around day, shooting stuff, coming home to hot, meaty meals – they are living the good life. Shepherding is the rare job where staring at the clouds counts as work.

Or Mongols. I mean, yee-haw – why they ain’t nuthin’ but Chinese cowboys, amirite? For Kazakhs, Mongols and cowboys when there’s a problem: to hell with it – let’s just move, nature will take care of itself.

You know who never appeared very free to me? The Dutch. Windmills, trading, constant fear of floods…seems like a lot of endless dike maintenance and perpetual worry over unsold goods.

England, too – somehow they are the supposed to be the freest in mind, body and body politic, yet they get apoplectic if you jump the queue?

People don’t appreciate this, but the French are perhaps a whopping 2% less rigid and slavish to doctrine than the neighbouring Germans, who are considered the world’s most dangerously anal-retentive. For whatever reason, the French don’t go postal or conquer Europe – they just commit suicide.

Let’s get serious: Western “liberty” from 1491-1917 was solely for the 1%. Serfdom, debt slavery, work slavery and actual slavery – this was the lot of the European masses.

Even after the French Revolution abolished feudalism, the bourgeois, West European, Liberal Democratic system was only appreciated and celebrated by the rich, who owned the printing presses and from whom the governing political class was entirely drawn.

Let’s stop the stupidity, and start examining the history of the modern notion of freedom from an standpoint which passes the smell test. Western jingoists – you can go back to admiring your prematurely wrinkled White mug in the mirror.

The recent non-fiction book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus is a very well-received examination of often-superior intellectual, cultural and societal achievements of the New World prior to Columbus. It takes a largely anthropological and scientific tack, but it tangentially relates how one of the things West Europeans brought back home was an entirely new concept of personal freedom.

Colonizers asked themselves: ‘Are we really free inside this imperialist prison/fort?’

“Adriaen van der Donck was a lawyer who in 1641 transplanted himself to the Hudson River Valley, then part of the Dutch colony of Nieuw Netherland. He became a kind of prosecutor and bill collector for the Dutch West India Company, which owned and operated the colony as a private fiefdom. Whenever possible, van der Donck ignored his duties and tramped around the forests and valleys upstate. He spent a lot of time with the Haudenosaunee, whose insistence on personal liberty fascinated him. They were, he wrote, ‘all free by nature, and will not bear any domineering or lording over them.’

When a committee of settlers decided to complain to the government about the Dutch West India Company’s dictatorial behaviour, it asked van der Donck, the only lawyer in New Amsterdam, to compose a protest letter and travel with it to the Hague. His letter set down the basic rights that in his view belonged to everyone on American soil – the first formal call for liberty in the colonies. It is tempting to speculate that van der Donck drew inspiration from the attitudes of the Haudenosaunee.

The Dutch government responded to the letter by taking control of New Amsterdam from the Dutch West India Company and establishing an independent governing body in Manhattan, thereby setting into motion the creation of New York City. Angered by their loss of power, the company directors effectively prevented van der Donck’s return for five years. While languishing in Europe, he wrote a nostalgic pamphlet extolling the land he had come to love.

Every fall, he remembered, the Haudenosaunee set fire to the ‘woods, plains and meadows,’ to ‘thin out’….

The author goes on to describe how controlled burns were used to attract bison, which is some of the abundant proof he relates showing how Indians shaped their environment as much as Europeans did theirs, but did so in ways that were incomprehensible to the imperialists, who believed it was “unspoiled nature”. 1491 is primarily a scientific book, but this article is “tempting to speculate” on the origins of modern freedom.

So, the “first formal call for liberty in the colonies” – the first demand for proletarian-99% rights – was the result of trying to emulate the American Indians?

Makes total sense: The greatest cultural ideas usually come from cross-pollination – from jazz to ancient Greece (which was half-Turkish). European imperialists, cowering in their forts, surely discussed the Indians’ culture…and surely they adopted some of the Indians’ positive ideas.

Neighbors of the Onondaga Nation

Understanding Haudenosaunee Culture

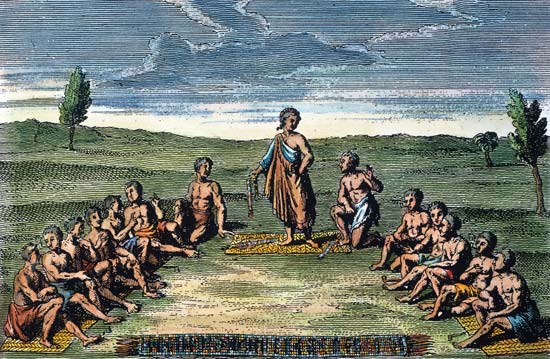

Leaders from five Iroquois nations (Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca) assembled around Dekanawidah c. 1570, French engraving, early 18th century. (Granger Collection, NY)

Who are the Haudenosaunee?

Haudenosaunee is the general term we use to refer to ourselves, instead of “Iroquois.” The word “Iroquois” is not a Haudenosaunee word. It is derived from a French version of a Huron Indian name that was applied to our ancestors and it was considered derogatory, meaning “Black Snakes.” Haudenosaunee means “People building an extended house” or more commonly referred to as “People of the Long House.” The longhouse was a metaphor introduced by the Peace Maker at the time of the formation of the Confederacy meaning that the people are meant to live together as families in the same house. Today this means that those who support the traditions, beliefs, values and authority of the Confederacy are to be know as Haudenosaunee.The founding constitution of the Confederacy brought the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk nations under one law. Together they were called the Five Nations by the English, and Iroquois by the French. The Tuscarora joined around 1720, and collectively they are now called the Six Nations.We also refer to ourselves as Ongwehonweh, meaning that we are the “Original People” or “First People” of this land. The Haudenosaunee is actually six separate nations of people who have agreed to live under the traditional law of governance that we call the Great Law of Peace. Each of these nations have their own identity, In one sense, these are our “nationalities.” Many of the names that we have come to know the tribes by are not even Indian words, such as Tuscarora or Iroquois. The original member nations are:Seneca, Onondowahgah, meaning The People of the Great Hill, also referred to as the Large Dark Door.

Cayuga, Guyohkohnyoh, meaning The People of the Great Swamp.

Onondaga, Onundagaono, meaning The People of the Hills.

Oneida, Onayotekaono, meaning The People of the Upright Stone.

Mohawk, Kanienkahagen, meaning The People of the Flint.

Tuscarora, known as Ska-Ruh-Reh meaning The Shirt Wearing People.

What is the Great Law of Peace?

The Great Law is the founding constitution of the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy. It is an oral tradition, codified in a series of wampum belts now held by the Onondaga Nation. It defines the functions of the Grand Council and how the native nations can resolve disputes between themselves and maintain peace.

The Peacemaker traveled among the Iroquois for many years, spreading his message of peace, unity and the power of the good mind. Oral history says that it may have taken him forty some years to reach everyone...[and that] he was met with much skepticism...he continued and was able to persuade fifty leaders to receive his message. He gathered them together and recited the passages of the Great Law of Peace. He assigned duties to each of the leaders...he selected the women as the Clan Mothers, to lead the family clans and select the male chiefs...The Peace Maker then established clans among the Haudenosaunee as a way to unite the Five Nations and as a form of social order.

What are the Underlying Values of Haudenosaunee Culture?

Our culture is a way of thinking, a way of feeling, but also an intuitive way of problem solving and a unique way to express ourself in the world. The Haudenosaunee call all of this “Ongwehonweka” meaning all of things that pertain to the way of life of the Original People. Ongwehonweka includes all of the values, mores, ethics, philosophy and beliefs that we have inherited from our ancestors.

Values

There are shared values held by each generation that contribute to the concept of the self. Values are shared principles that are considered important in life, that include:

- Thinking collectively, considering the future generations.

- Consensus in decision making, considering all points of view.

- Sharing of the labor and benefits of that labor.

- Duty to family, clan, nation, Confederacy and Creation.

- Strong sense of self-worth without being egotistic.

- People must learn to be very observant of the surroundings.

- Everyone is equal and is a full partner in the society, no matter what their age.

- The ability to listen is as important as the ability to speak.

- Everyone has a special gift or talent that can be used to benefit the larger community.

Mores

There are mores that are the customs that are considered essential to maintaining the characteristics of the community:

- Clanship relations and names are important. Clan identity impacts on nearly all aspects of the social, political and spiritual organization of the community.

- Council Chiefs protect the welfare of the people.

- Clan Mothers maintain social harmony.

- Faithkeepers keep the ritual order moving.

- Annual cycles of thanksgiving help establish order and rhythm.

- The arts connect the generations in spirit.

- The native languages are the keys to the expressions of the soul.

Ethics

| • To be generous | • To feed others | • To share |

| • To be thankful | • To show respect | • To be hospitable |

| • To honor others | • To be kind | • To love your family |

| • To be cooperative | • To live in peace | • To live in harmony with nature |

| • To be honest | • To ignore evil or idle talk |

Conclusion

Agriculture was the main source of food. In Iroquois society, women held a special role. Believed to be linked to the earth's power to create life, women determined how the food would be distributed — a considerable power in a farming society. They were also responsible for selecting the sachems for the Confederacy. Iroquois society was MATRILINEAL; when a marriage transpired, the family moved into the longhouse of the mother, and FAMILY LINEAGE was traced from her.

The Iroquois society proved to be the most persistent military threat the European settlers would face. Although conquest and treaty forced them to cede much of their land, their legacy lingers. Some historians even attribute some aspects of the structure of our own Constitution to Iroquois ideas. In fact, one of America's greatest admirers of the Iroquois was none other than Benjamin Franklin.

END OF SIDEBAR

We must remember that West Europeans have no nomads, no roaming Kazakhs showing what real freedom is. West Europeans hate the nomadic Roma, constantly refusing them entry into society, and they even wiped out the nomadic, poetic troubadours during the 13th century Albigensian Crusades.

It’s a question of geographic determinism: only France has the huge areas which would allow nomadic freedom to flourish. While they do have a tradition of the transhumance, this is peaceful pastoralism and not Turkic tribes kicking butt and taking names from the Caucuses to Siberia. An older Frenchman in southern France once told me the story of the last local shepherd: the guy lived totally with his sheep, was constantly covered in excrement, and was regularly hounded out of town. Clearly, nomads weren’t wanted.

Quite a different lifestyle than, say, the nomadic tribes of early Islam. Of course, they were washing five times a day, as cleanliness is next to godliness, and they were undoubtedly the most close to (the One, monotheistic) God. They also kicked butt in the sociopolitical-religious Revolution of Islam, which was an unparalleled insistence on human equality and individual rights across the board, providing us with another example of nomads knowing true freedom.

The Aztec and Incan civilisations didn’t have nomadic cultures, and they also did not have this Northeast American concept of liberty. Their societies were highly stratified, and again we can point to geographic determinism: the humid marshes of Central America and the Andes prevent such open-spaced freedom. But they got by:

“Tenochtitlan dazzled its invaders – it was bigger than Paris, Europe’s greatest metropolis. The Spaniards gawped like yokels….”

A drawing of what part of Tenochtitlan may have looked like. Spanish conquistador Cortes used tribes oppressed by the Aztec imperialists, like the Tlaxcalans, to help his soldiers defeat Montezuma.

“Unlike Western cities, Tiwanaku (Peru, apex 500-900 AD) had no markets (The author has, strangely, italicised the word ‘markets’, apparently because the idea is so shocking. He is, of course, from the US.)…. Andean societies were based on the widespread exchange of goods and services, but kin and government, not market forces, directed the flow. The citizenry grew its own food and made its own clothes, or obtained them through their lineages, or picked them up in government warehouses.”

Clearly, just being “Indian” didn’t make one uber-free – it was specific to a certain region. Certainly, Westerners make this claim this today.

An interesting passage describes the sociopolitical culture of the Northeast American Indian Tisquantum (Squanto), who is a modern American hero for aiding the European imperialists in order to gain political power over other tribes – same old story: using sectarianism to divide and conquer. (See: Lebanon)

“Although these settlements were permanent, winter and summer alike, they often were not tightly-knit entities, with houses and fields in carefully demarcated clusters. Instead, people spread themselves through estuaries, grouping into neighbourhoods, sometimes with each family on its own, its maize ground proudly separate. Each community was constantly ‘joining and splitting like quicksilver in a fluid pattern within its bounds,’ wrote Kathleen J. Brandon, an anthropologist at the College of William and Mary – a type of settlement, she remarked, with ‘no name in the archeological or anthropological literature.’”

Sort of semi-nomadic. It’s also very similar to US society today, where people move 3,000 miles at the drop of a hat and are “proudly separate” from neighborhood, work, religious and economic ideas of solidarity and unity. Maybe it’s in the soil?

These tribes were overseen by a sachem, who was clearly no West European feudal lord.

“As a practical matter, sachems had to gain the consent of their people, who could easily move away and join another sachemship.

During this time, the early 17th century, no ruler in Western Europe “had to gain the consent of their people” – only the consent of their nobility.

So what “Western notion of freedom”?! Such an idea was totally foreign to them – it had to be imported. And that’s the point of this article – West European/Western notions of “freedom” are not at all indigenous, and should be attributed to American Indians.

I doubt this is the first time these ideas have been broached, but they certainly aren’t broadcast often.

Kazakhs never believed Westerners ‘created freedom’ anyway – why should we?

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]f course, it was not until the advent of socialism that this American Indian idea of humans being “all free by nature” started to take effect in the West.Even then, for yet another century Western “freedom” extended only to Whites, and often only to White men. The idea of true freedom was obviously quite difficult for them to accept and incorporate. It took about as long as it did to accept the concept of Abrahamic monotheism (and even then they still usually prefer they polytheistic-influenced idea of three, instead of the Jeish and Islamic One).

Russia was the only “European” country which had contact with nomads, and it’s also “tempting to speculate” that this explains why they were the first “Western” nation to embrace Socialist Democracy, which honors individual freedom far more than Liberal Democracy.

The point of this article is not to denigrate Westerners, but to remind us of how very immature our globe is: we have spent only a fraction of human history honestly examining other cultures. Instead, we have been self-serving, racist, seeking to justify capitalism-imperialism, and refusing to embrace the socialist worldview which fundamentally sees races and cultures as equal, worthy of protection, and worthy of emulation.

It is unfortunate that West Europeans didn’t have much contact with nomadic philosophy but, thankfully, the New World was able to provide that, and we can all celebrate the synthesis.

“Now envision this kind of fruitful back-and-forth happening in a hundred ways with a hundred cultures – the gifts from four centuries of cultural exchange. One can hardly imagine anything more valuable. Think of the fruitful impact on Europe and its descendants from contacting Asia (and the Islamic World). Imagine the effect on these places and people from a second Asia.”

Of course there was a political and intellectual give-and-take between American Indian “savages” and the smallpox-scarred conquistadors/religious zealots of West European society – why deny that?

What Westerners mainly gave was the mighty microbe, which wiped out perhaps 95% of the New World’s population in their first 130 years of contact with Old Worlders. That exact percentage cannot be known, but what obviously occurred was humanity’s worst regional era of human, psychological, cultural and economic depression.

“The simple discovery by Europe of the existence of the Americas caused an intellectual ferment. How much grander would have been the tumult if Indian societies had survived in full splendor!”

1491 is a good book because that is essentially its honourable thesis. Some Indians obviously had much to teach Europeans about freedom, even in their weakened condition. Let’s give them the credit they deserve.