In Focus: Understanding what the police is, whence it came, and what can be done about it

ANNOTATED BY PATRICE GREANVILLE

PREFATORY NOTE

The existence of police and the act of "policing" encompass many functions that have organically evolved over the centuries. In most cases, police forces were not created and do not serve, even today, chiefly to protect the populace against violence and criminality from their peers, but to serve as protectors—taxpayer-supported shields— for big property and the privileges of persons of high standing in society—nobles, big landowners (almost always nobles in pre-modern societies) and finally big industrial magnates and their high retainers in our time. This particular group, a puny segment of society not much larger than 0.001% in the US, comprises the chief beneficiaries of capitalist regimes, the ruling class in self-denominated "capitalist democracies", a deliberately misleading oxymoron.

This role of the police—often an offshoot of an standing army (Chile's famous Carabineros used to be a regular army regiment), decommissioned soldiers, or an ad hoc corps with variegated origins (look for example into the creation, role and eventual dissolution/transformation of the Guardias de Asalto (Assault Guard) in Spain), and the existence of supporting local militias—has been observed in diverse sedentary civilizations across the globe since antiquity (1). Thus ancient Egypt, Rome, the Mesopotamian kingdoms and empires, and Chinese emperors, all had recourse to some form of organised guard or force to provide constant protection for the ruling caste and the day to day enforcement of state functions and specific royal commands. Law enforcement relating to taxation, conscription, and "peacekeeping" according to the established rules and customs of the social order (especially in the countryside (2)) and in many cases the whims of the monarchs or regional potentates (dukes, counts, popes, bishops, etc.), represented the bulk of the police job. From inception, this role automatically made the police a conservative, highly militarised, coercive force charged with the preservation of the status quo.

In this series, we will try to discuss this subject from various perspectives.

—PG

Part One: Police origins

1.1 History of the police, as seen by a friendly source (mainstream view)

A Brief History of Law Enforcement

CBS Blue Bloods is a latter day cop show with the usual plot lines, albeit modernized for 21st century audiences. Police melodramas are an old staple of American television. Cheap plots with plenty of opportunity for mayhem and "wow" moments, they also reinforce the status quo by giving the police a free public relations boost.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]lthough the police are an ever-present force in our lives—providing protection, enforcing the law, preventing crime and maintaining order—the form they take today took hundreds of years to perfect. Nearly 400 years ago, the U.S police force as we know it was merely in its infancy. Policing in Europe, however has been around in some form since 3000 BC.

The word police comes from the ancient Greek word, polis, meaning “city.” The first policing organization, however, began in about 3000 BC in Egypt. Pharaohs were in charge of appointing an official to oversee and enforce justice and security for each jurisdiction. This official was assisted by the area's tax collector. Ancient Greece also had a police force made up of Scythian slaves who were regulated by magistrates. Ancient Rome continued the practise of recruiting lower-class citizens (sometimes with criminal pasts) to be part of the police force. These teams of men were in charge of protecting the city, but prosecuting everyday crimes (even murder) was often left to be resolved between individuals. Emperor Augustus created three groups of police to protect Rome from crime and fire in 6 AD. These men were recruited from the Roman Army.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 5th century, the Byzantine Empire went back to the original model of law enforcement where most crimes were left to be dealt with by individuals. In England, however, a new structure of police was being formed. In this model, groups of 100 men were responsible to enforce good conduct between each other while protecting the community. These groups were headed by a Shire-Reeve. The role of the Shire-Reeve eventually developed into what we know today as a Sheriff. By the late 13th Century, the role of Constable was created. Constables were responsible for overseeing the night watch and for providing security. At this time, the investigation and prosecution of crimes was still left up to individuals.

In 1285, the Statute of Winchester made enforcing the law a social responsibility. Any person who didn't report or try to stop a crime could be prosecuted. In 1361, the Justice of the Peace Act revoked public responsibility and placed it on the Justices who were appointed by the monarch. Their responsibilities included police, judicial and administrative duties. Law enforcement in England rested almost solely on the shoulders of Justices, Constables and the night watch until the 19th Century.

In 1631, Boston became the first U.S city to establish a night watch. New Amsterdam (later New York City) soon followed suit in 1647. In the late 18th and 19th Centuries, “regulators” (vigilantes) became commonplace in many U.S cities. Their role was to enforce order in areas where there was none.

It wasn't until 1829 that the Metropolitan Police Act was passed and the London Metropolitan Police Department was formed. The structure of the department was based on the military. This law enforcement model went on to influence police departments in Great Britain, the British Commonwealth and the United States.

In the middle of the 19th Century in the U.S, laws were passed in order to regulate social behaviour, and penitentiaries, asylums and official police forces were established. New York City was the first to have an official police department in 1844. The NYPD was based on the London Metropolitan Police Department. Soon after, departments were established in New Orleans and Cincinnati (1852), Boston and Philadelphia (1854), Chicago and Milwaukee (1855), and Baltimore and Newark (1857). Authority over police was left to neighbourhoods and neighbourhood leaders. Officers didn't wear uniforms and the initial function of the police was to prevent crimes. Once this proved a very difficult task, one of their main purposes became investigating crimes that had already been committed. The first detective unit began in New York City in 1857.

In the mid to late 19th Century, U.S police were still governed mostly by the communities they were serving. Because of this, corruption and political favoratism were rampant and created major problems. By the end of the century, with much public influence, the police force became a civil service with control of the force being placed on the city and/or the state.

In the mid to late 19th Century, U.S police were still governed mostly by the communities they were serving. Because of this, corruption and political favoratism were rampant and created major problems. By the end of the century, with much public influence, the police force became a civil service with control of the force being placed on the city and/or the state.

Between 1900 and 1920, the prohibition movement, as well as fears of corruption and Communist influence lead to the need for Federal and State police organizations. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was created in 1908 to investigate antitrust and fraud cases, as well as crimes committed on government property or by government officials. In 1920, the Department of Treasury created the first large federal police agency which was in charge of enforcing prohibition. In order to deal with and prevent corruption and striking among local police forces, Pennsylvania established the first state police department in 1905. New York followed in 1917, Michigan, Colorado, and West Virginia in 1919, and Massachusetts in 1920.

Public confidence in the police was waning in the 20s and early 30s due to the effects of prohibition, corruption and the frightening growth in gangs and crime. August Vollmer began lobbying to professionalize the police in the early 20th Century. In 1916, he helped create the first university-level police educational program at the University of California, Berkeley. He also pushed for prosecution of delinquent youths, started the Uniform Crime Reports program which kept track of the annual national crime rate, and helped to abolish the physical and/or mental torture the police had been using in suspect interrogation.

J. Edgar Hoover became head of the FBI in 1924 and began actively trying to change the image of detectives, the Bureau, and the police force as a whole. He made it mandatory for new agents to have a formal education, nearly eliminated corruption and almost single-handedly restored public opinion of the police. A new model was adopted which became known as the “three R's”: random preventive patrols, rapid response to calls for service, and reactive criminal investigation. This model, as well as Hoover's military-based structure of the police force became commonplace among all departments. (Op cit., badgeandwallet.com) (3)

1.2 History of the police: A radical view

By T.P. Wilkinson

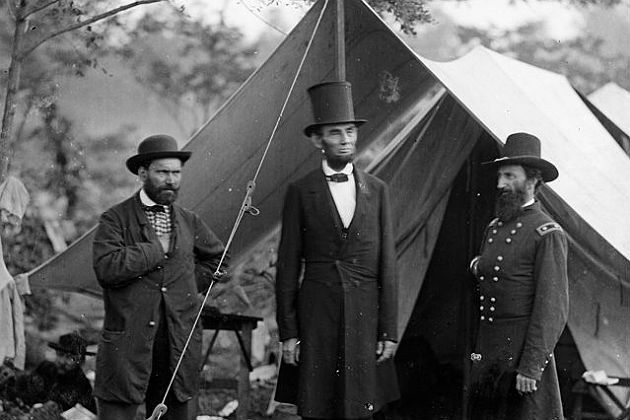

Born to poverty in Glasgow, Allan Pinkerton (l) first served Lincoln as a spymaster for the abolitionist side, but after the war he became a tool for the lords of capital renting his private army of detectives and spies to defeat labor.(4) The Pinkerton Agency also worked internationally, assisting the Spanish government in 1872 to suppress a revolution in Cuba — a demonstration of Pinkerton’s rather flexible morality. His exploits foreshadowed both the work of the FBI and the CIA.

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hile it may be common knowledge that fire departments originated as private organisations to defend the interests of property insurers, it has probably been forgotten that in the US police were originally the hired gangs of landowners and merchant-industrialists. As urban conurbations like New York City grew, the police were the action arm of the political machines that served to dominate native and immigrant workers. A job in the police department was a patronage post, i.e. one either bought a job or by demonstrated willingness to act for the political boss(es) could be given a shield, a license to use violence and commit crimes on behalf of the machine or for personal gain as long as it did not conflict with the interests of the former.

Not only was the struggle for democratic and socialist government subverted by imposing "pwogwessive" public administration, these professional governments were equipped with private armies which were then given a badge and virtual immunity from any form of civil or criminal prosecution. Although some may know the history, it is important to recall that these policies were developed, supported and ultimately imposed by the plutocrats of the 19th century, Morgan, Rockefeller, Carnegie, later Ford and others both directly and through philanthropic foundations-- established to evade taxes and distribute bribery.

Revelers in Wisconsin celebrate the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, after 20 years in which the law created a massive crime problem and an equally massive police presence.

After World War I those owners sought means to establish federal jurisdiction over political dissent, especially given the enormous numbers of urban immigrants from inferior European stock. People like Henry Ford realised that suppressing the consumption of alcohol would create a nationwide pretext for social control without openly contravening the supposed constitutional liberties, e.g. the First Amendment or those forbidding unreasonable search and seizure or denial of due process. The Volstead Act was adopted [in 1920] and the Prohibition amendment entered into force. For the first time since the Civil War, the federal government had a mandate to coordinate policing throughout the US and to mobilise the corporate machine police forces for political control. This not only made families like the Kennedys and Bronfmans fabulously rich, it helped establish the corporate form of crime of which Meyer Lansky became the paragon (although popular culture focuses on Italians rather than Jews).

Greek director Costa Gavras' film State of Siege focused on the Mitrione case in Uruguay. Most Americans have never understood that their government trains torturers and death squads across the globe, while mouthing pieties about freedom and democracy at home.

It is against this background that one needs to understand the decades of opposition to police in the US, mainly from non-white and poor communities in the US. This opposition is not based on occasional abuse or failures in training. It is based on the intuitively recognised fact that the police in the US-- as in the rest of the US Empire-- are an army of occupation. They are, individual police officers of good faith notwithstanding, the daily terror and threat of terror which is the complement to Hollywood propaganda and the dictatorship of the workplace. It is no accident that someone like Dan Mitreone, an Indiana police chief, became a notorious trainer of torturers in Latin American police forces before he was kidnapped [by guerrillas] and executed. Michigan State University ran, or served as a conduit for, programs throughout the US war against Vietnam which brought members of these municipal terror organisations to Southeast Asia to torture Vietnamese.

An iconoclastic thinker by nature, and a good example of a Renaissance man in our time, Dr. T.P. Wilkinson writes, teaches History and English, directs theatre and coaches cricket between the cradles of Heine and Saramago. He is also the author of the book Church Clothes, Land, Mission and the End of Apartheid in South Africa. Most of his work since 2015 has been posted at Dissident Voice where he also have contributed a poem every Sunday since then. Prior to that, pieces were posted at Global Research, Black Agenda Report and while Alexander Cockburn was still alive at Counterpunch. He is now an increasingly familiar voice in the world's leading anti-imperial publications.

An iconoclastic thinker by nature, and a good example of a Renaissance man in our time, Dr. T.P. Wilkinson writes, teaches History and English, directs theatre and coaches cricket between the cradles of Heine and Saramago. He is also the author of the book Church Clothes, Land, Mission and the End of Apartheid in South Africa. Most of his work since 2015 has been posted at Dissident Voice where he also have contributed a poem every Sunday since then. Prior to that, pieces were posted at Global Research, Black Agenda Report and while Alexander Cockburn was still alive at Counterpunch. He is now an increasingly familiar voice in the world's leading anti-imperial publications. JIMMY DORE: Most Cops Are Criminals And Here's The Proof

(1) Nomads and hunter-gatherers tribes organised along the lines of primitive communism seem to escape this phenomenon entirely or to a large extent.

The memorable, devious "bandido" in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, an iconic film, had the outlaw swiftly dispatched by the rurales. The reality, as usual, was more complex.

(2) Projecting the needs and fears of the big landowning elites, some form of countryside police has been in effect for centuries. In modern times, Mexico and Spain offer interesting examples. Sharing the same original functions, the brutish and widely feared Guardia Civil in Spain and the notoriously heavy-handed Mexico’s “Federales” —or countryside police (in actuality in most cases units of the Mexican army, not to be confused with the “rurales”—rural mounted police— also serving the same function), these forces were tasked with the pacification of the peasantry. Summary justice against “bandidos” or anyone accused of such was usually the favored method, which in many cases equated with broad daylight death squad activity against “subversives” or, conveniently, anyone merely accused of being one. Both Federales and rurales were largely eliminated (dissolved) by specific treaties during the Mexican revolution. But the elimination/transformation of police forces in the wake of a genuine revolution is one of the toughest tasks for any new government, especially one advocating new social values. The Cuban, Chinese and of course Russian revolutions have important lessons in this regard. As suggested earlier, there is no general, ideal or quick solution to this knot, as all police forces around the globe reflect their countries' histories and cultures, and specific turning points in their development.

(3) The FBI came into existence in the first decade of the 20th century (formally c. 1908) under AG Charles Bonaparte, during the Teddy Roosevelt administration. The Bureau of Investigation, as it came to be called, was to operate as a detective force for the Justice Department which, until then, had to borrow detectives from the Secret Service to fill specific tasks. By 1919, in the wake of the first Red Scare and the consequent "Palmer Raids", the Bureau was acquiring its true and principal character as an agency focused on combatting subversion against the established order. Open persecution and spying on US nationals protected by the Constitution could not be admitted, nor did it sit well with some members of Congress and important public officials (yes, we had them in those days), so the Bureau soon found itself developing a proper cover for its real mission, a non-political "crime" fighting force which gave J.E. Hoover immense popularity in the ensuing decades as his "G men" busted one notorious violent gang after another, or so the public was told.

In June 1919, Attorney General Palmer told the House Appropriations Committee that all evidence promised that radicals would "on a certain day...rise up and destroy the government at one fell swoop." He requested an increase in his budget to $2,000,000 from $1,500,000 to support his investigations of radicals, but Congress limited the increase to $100,000.[7]

An initial raid in July 1919 against an anarchist group in Buffalo, New York, achieved little when a federal judge tossed out Palmer's case. He found in the case that the three arrested radicals, charged under a law dating from the Civil War, had proposed transforming the government by using their free speech rights and not by violence.[8] That taught Palmer that he needed to exploit the more powerful immigration statutes that authorized the deportation of alien anarchists, violent or not. To do that, he needed to enlist the cooperation of officials at the Department of Labor. Only the Secretary of Labor could issue warrants for the arrest of alien violators of the Immigration Acts, and only he could sign deportation orders following a hearing by an immigration inspector.[9]

On August 1, 1919, Palmer named 24-year-old J. Edgar Hoover to head a new division of the Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation, the General Intelligence Division (GID), with responsibility for investigating the programs of radical groups and identifying their members.[10] The Boston Police Strike in early September raised concerns about possible threats to political and social stability. On October 17, the Senate passed a unanimous resolution demanding Palmer explain what actions he had or had not taken against radical aliens and why.[11]. (Se Palmer Raids, Wikipedia)

(4) "Between 1877 and 1892, the Pinkertons were involved in 70 labor union strikes—including some of the biggest and most consequential of the Gilded Age. After Allan Pinkerton’s death in 1884, his sons William and Robert took over, and they doubled down on the project of providing what capitalists and industrialists needed in their struggles with labor. Pinkerton detectives infiltrated labor unions under cover of secrecy, and reported on their activities to employers; Pinkerton guards, acting as visible muscle, protected company property during strikes. The Pinkertons also provided strikebreakers (aka scabs) to fill in for companies when union workers walked out and protected those strikebreakers while they were working." (Rebecca Onion, Who were the Pinkertons?, Slate, Feb. 1, 2019).

[premium_newsticker id=”211406″]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

ALL CAPTIONS AND PULL QUOTES BY THE EDITORS NOT THE AUTHORS

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in Deiner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

[google-translator]