RELIGION & THE TREATMENT OF GOD’S CREATURES

By Colman McCarthy

This essay was first published on December 25, 1995

In the Nativity narratives found in the Christian scriptures, only St. Luke states that Jesus was born in a dwelling for animals.

Which kind of animals? How many were there?

We aren't told. It's been left to tradition to establish that sheep and oxen -- two species prevalent at that time in rural Bethlehem and first-century Palestine -- were sharing their space and straw with the Holy Family.

Regardless of the Bible's lack of specifics, that the birth of the Savior occurred among animals raises an obvious question: Is a message there, that nonhuman creatures have a value outside of what humans place on them? And if that value is present, does it lead logically to a moral obligation that humans have no right to keep on killing and exploiting animals for profit, sport or convenience?

However those questions are ultimately answered -- and pews are filled with theologians and biblical exegetes advancing opposite arguments with the-Bible-tells-me-so certainty -- little dispute exists that in the ministry of Christ animals enjoyed a preeminence.

As an educated and scripturally aware Jew, Christ had a natural concern for animals. In St. Mark's Gospel, he begins his teaching in the wilderness "with the wild beasts." When baptized by John in the Jordan, Mark states, "The Spirit, as a dove," descended on Jesus. In anger, Christ drove money-changers from the temple where they were profiteering off doves. Christ said sparrows are not "forgotten before God." St. Luke writes: "Foxes have holes and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head."

In the Hebrew scriptures, animals are honored. In Genesis, they were created on the same day, the sixth, as humans. A few lines later in Genesis, an animal-free diet is commanded. The Psalmist cries, "O Lord, you preserve man and beast" and describes God as "satisfying the desire of every living creature."

In "Animal Theology," Andrew Linzey, an Anglican priest currently holding the world's first fellowship in theology and animal rights at Oxford University, writes: "While it is true that there is a great deal we do not know about Jesus' precise attitudes to animals, there is a powerful stand in his ethical teaching about the primacy of mercy to the weak, the powerless and the oppressed. Without misappropriation, it is legitimate to ask: Who is more deserving of this special compassion than the animals so commonly exploited in our world today. Moreover, it is often overlooked that in the canonical Gospels Jesus is frequently presented as identifying himself with the world of animals."

Linzey's argument for Christlike compassion to animals isn't a view with much current popularity, even -- perhaps especially -- among his fellow clergy. On Nov. 24 in Surry, Va., God, guns and gore came together in a state park. Before 27 shotgun-toting deer-slayers and their 36 dogs hied into a l,000-acre wood, a local Episcopalian priest, the Rev. Thomas Bauer, prayed to the Lord for a blessing: "As you hounds are faithful to your masters, may your masters be faithful to God."

As reported by the New York Times, the Virginia gunners, who had paid $250 to the Southern Heritage Deer Hunt for the prayerful outing, had easy pickings. Six bucks and nine does were killed by noon.

Rounding up a clergyman in white linen vestments for the purpose of sanctifying the killing of animals doubtlessly added a touch of elegance to the Surry hunt. Rev. Bauer's prayer was a traditional Anglican blessing of the hounds, dating to the days of yore when mounted tallyhoing English gentry took the fences and fields in search of game.

Rounding up a clergyman in white linen vestments for the purpose of sanctifying the killing of animals doubtlessly added a touch of elegance to the Surry hunt. Rev. Bauer's prayer was a traditional Anglican blessing of the hounds, dating to the days of yore when mounted tallyhoing English gentry took the fences and fields in search of game.

Earlier this year, another of God's ministers sought to create an aura of holiness for the shotgun set in his flock. A "Coon Hunt for Christ" was organized in rural Limestone County, Ala., by the Rev. Charles Hood of the Union Hill Cumberland Presbyterian Church. The event, organized as a fundraiser to help build a sanctuary, saw 133 hunters, including several 12 or younger, pay entry fees for the thrills of siccing dogs on coons chased up trees where they were shot and later devoured as coonburgers. About $2,500 was raised. "The coon hunt," Pastor Hood told the Huntsville Times "is a way to spread the word of God, to talk about Jesus Christ."

The events in Surry and Limestone have both their theological and environmental defenders. The clamor this past autumn has been to kill more deer, not fewer as Andrew Linzey would like. The deer are everywhere, it was said: nibbling precious flowers in suburban gardens, gamboling on highways, darting across airport runways and acting, in general, as if they own the place.

Which, of course, they don't. They co-own it, with humans.

Theologians separate on that issue. They debate whether the first reference to animals in the opening lines of Genesis -- "Let {man} have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air and over the cattle, and over all the wild beasts of the earth" -- means a right to kill and exploit or is a call to stewardship and protectiveness.

Until lately, the first view has prevailed, with rarely a suggestion that it is even open to question. Thomas Aquinas, the orotund 13th-century Italian theologian, stated in "Summa Contra Gentiles" that "by divine providence" animals "are intended for man's use in the natural order. Hence it is not wrong for man to make use of them, either by killing them or in any other way whatever."

St. Thomas was a philosophical giant, but his antropocentric beliefs blinded him to the duty to extend justice to animals, the most oppressed beings on earth.

Aquinas went further in "Summa Theologica." Animals are not owed even kindness out of charity: "The love of charity extends to none but God and our neighbor . . . The word neighbor cannot be extended to irrational creatures, since they have no fellowship with man in the rational life." Thus "charity does not extend to irrational creatures."

Thomistic thinking has been the theological mooring of the Roman Catholic Church for the past seven centuries. It has been endorsed by popes, including the current one. Under John Paul II, the new Catholic catechism, published earlier this year, rules that "animals, like plants and inanimate beings, are by nature destined for the common good of past, present and future humanity." Animals "may be used to serve the just satisfaction of man's needs."

Among the Catholics rejecting that teaching is Virginia Bourquardez, the 83-year-old founder of the Washington-based International Network for Religion and Animals. In the group's Fall 1995 newsletter (P.O. Box 77591, Washington, D.C. 20013), Bourquardez writes: "We destroy the integrity of the animal creation when we forget that God-given animals have a right to fulfillment of their natural lives independent of human existence. It is catastrophic that religion (both eastern and western traditions, except for the Jains) has chosen to focus only on the human creation, neglecting over these many years the other two forms of life as described in the Creation story: nature and animals."

Bourquardez, who writes that her Catholic faith these many years "has been the love of my life and its guiding light," announced she is taking "a leave of absence" from the church. When it honors the rights of animals, she said, "then I will come back with wide open arms to fight other battles within your confines."

Now on the outside but still devoutly religious, Bourquardez isn't exactly alone among believers. The Dalai Lama wrote in 1967: "Killing animals for sport, for pleasure, for adventures, and for hides and furs is a phenomenon which is at once disgusting and distressing. There is no justification for indulging in such acts of brutality."

Among Western theologians, only a few have chosen to explore with any depth the meaning of stewardship and the resulting obligation to peaceful coexistence with animals. Linzey, who would have been praying with the deer in Surry and the coons in Limestone County, is at the forefront. In "Compassion for Animals: Readings and Prayers," he writes:

"When we turn to the saints, we find, almost without exception {a portrayal of a} world of cosmic peace. We know so well the picturesque stories of St. Francis preaching to the birds, St. Giles' rescuing deer, or St. Columba's saving of the crane that we simply overlook their theological significance. Many of the stories may appear sentimental, but none of them in fact is simply concerned with sentiment. Their purpose is deeply serious, and it is perhaps a sign of our lost innocence that we fail to see their cardinal relevance today."

Linzey was influenced by Albert Schweitzer, the German theologian and physician whose work "Reverence for Life" endures as a classic text. In it, he stated that "Ethics {means} responsibility without limit to all that lives."

Yes, that's sweet, it has been and will be said, but what's to be done about all those deer unblessedly cavorting in America's gardens and on its highways?

One answer -- both theologically and environmentally sound -- is that humans, not deer, are causing the problem. State wildlife officials, happily serving the munitions industry, welfare ranchers and gunners, have manipulated habitats, altered predator-prey relationships and ignored fertility control programs.

Hunters mostly go after full-grown stags. That leaves herds with more does to produce more fawns. Hunting increases herd size.

With the state complicit in violent non-solutions to the deer problem, many are asking when is the church going to break ranks and look at God's creatures with stewardly mercy? With the altars of Christian churches adorned with creches, which include animals, Christmas would be the apt time to begin.

Should the clergy need a text for the occasion, there is the counsel of Father Zossima in "The Brothers Karamazov" by Feodor Dostoevski. In one of the most stirring sermons found in world literature, the wise elder addresses his monastic community:

"Love all God's creation, the whole of it and every grain of sand. Love every leaf, every ray of God's light . . . Love the animals: God has given them the rudiments of thought and untroubled joy. Do not, therefore, trouble it, do not torture them, do not deprive them of their joy, do not go against God's intent. Man, do not exalt yourself above the animals: they are without sin, while you with your majesty defile the earth by your appearance on it and you leave the traces of your defilement behind you -- alas, this is true of almost every one of us." CAPTION: Voices for Peaceful Coexistence

Among writings on the subject:

Thus godlike sympathy grows and thrives and spreads far beyond the teachings of churches and schools, where too often the mean, blinding, loveless doctrine is taught that animals have neither mind nor soul, have no rights that we are bound to respect, and were made only for man, to be petted, spoiled, slaughtered, or enslaved. -- John Muir, "The Story of My Boyhood and Youth"

Animals are part of God's creation and people have special responsibilities to them. The Jewish tradition clearly indicates that we are forbidden to be cruel to animals and that we are to treat them with compassion. These concepts are summarized in the Hebrew phrase tsa'ar ba'alei chayim, the biblical mandate not to cause "pain to any living creature." In Judaism, one who is cruel to animals cannot be regarded as a righteous individual. -- Richard H. Schwartz

Think of your feelings at cruelty practiced upon brute animals and you will gain the sort of feeling which the history of Christ's Cross and Passion ought to excite within you. -- Cardinal John Henry Newman

The mistreatment of animals in "intensive husbandry" is, then, part of this larger picture of insensitivity to genuine values and indeed to humanity and life itself -- a picture which more and more comes to display the ugly lineaments of what can only be called by its right name: barbarism. -- Thomas Merton

Surely we ought to show kind and gentleness to animals for many reasons and chiefly because they are of the same origin as ourselves. -- St. John Chrysostom

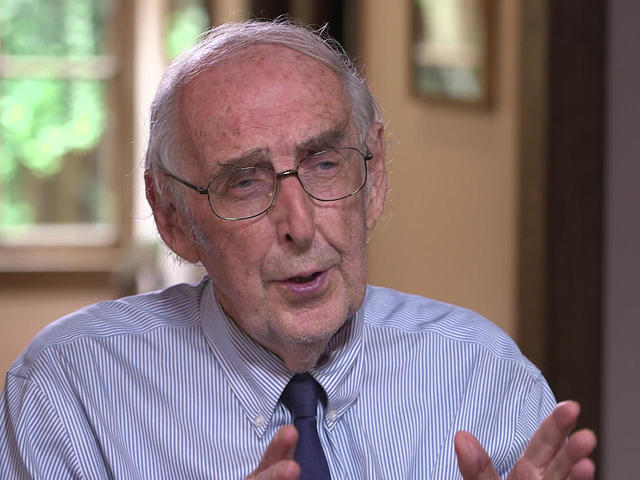

Colman McCarthy is a veteran peace activist, animal advocate and educator who founded and directs the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington, DC. He was a columnist for The Washington Post from 1969 to 1997. McCarthy is the author of All of One Peace: Essays on Nonviolence and editor of two anthologies, Solutions to Violence and Strength Through Peace: the Ideas and People of Nonviolence.

Colman McCarthy is a veteran peace activist, animal advocate and educator who founded and directs the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington, DC. He was a columnist for The Washington Post from 1969 to 1997. McCarthy is the author of All of One Peace: Essays on Nonviolence and editor of two anthologies, Solutions to Violence and Strength Through Peace: the Ideas and People of Nonviolence.

How can we speak of right and justice if we take an innocent creature and shed its blood? Every kind of killing seems to me savage and I find no justification for it. -- Isaac Bashevis Singer

Thank you for visiting our animal defence section. Before leaving, please take a moment to reflect on these mind-numbing institutionalized cruelties.

The wheels of business and human food compulsions—often exacerbated by reactionary creeds— are implacable and totally lacking in compassion. This is a downed cow, badly hurt, but still being dragged to slaughter. Click on this image to fully appreciate this horror repeated millions of times every day around the world. With plentiful non-animal meat substitutes that fool the palate, there is no longer reason for this senseless suffering. And meat consumption is a serious ecoanimal crime. The tyranny of the palate must be broken. Please consider changing your habits and those around you in this regard.

The wheels of business and human food compulsions—often exacerbated by reactionary creeds— are implacable and totally lacking in compassion. This is a downed cow, badly hurt, but still being dragged to slaughter. Click on this image to fully appreciate this horror repeated millions of times every day around the world. With plentiful non-animal meat substitutes that fool the palate, there is no longer reason for this senseless suffering. And meat consumption is a serious ecoanimal crime. The tyranny of the palate must be broken. Please consider changing your habits and those around you in this regard.

[premium_newsticker id=”211406″]