Anti-Stalin Falsehoods from a “Socialist” Writer

Grover Furr

Grover Furr

Resize text-+=

Grover Furr / April – May 2023

In the January – February 2023 issue of Current Affairs there appears an article titled “Stalin Will Never Be Redeemable/” Its subtitle reads:

Stalin was socialism’s worst enemy. History is easily forgotten, so nostalgia for the “Man of Steel” needs to be guarded against.

A person who knows of my long interest in Joseph Stalin and the “Stalin years” of Soviet history alerted me to this article when it appeared online. He wondered what my response to Skopic’s accusations against Stalin might be.

I have been studying the Stalin period of Soviet history for many years nowI decided to write a response to Skopic’s article because it is a brief compendium of many of the allegations made against Stalin not only by overtly pro-capitalist and anticommunist writers, but by persons who are, or wish to be, or think that they are, on the anti-capitalist Left.

I am not “defending” Stalin, much less “apologizing” for Stalin. I am searching for the truth, as determined by the best evidence available.

Every accusation Skopic makes about Stalin is demonstrably wrong. I prove most of them wrong on the evidence. A few are wrong because they are anachronistic -- charging Stalin (and the Soviet leadership, which was collective – Stalin was not a dictator) with failing to act according to knowledge we have today but that no one had at the time.

The present essay sets forth the evidence and my analysis of it. At the end I briefly address the question of how Skopic could be so wrong and the reasons for anticommunism in the first place.

|

Grover Furr Refutes the Anti-Stalin Falsehoods from Skopic’s article Stalin Will Never Be Redeemable Activist News Network

Jul 22, 2023 #Stalin

We are joined on the show by Dr. Grover Furr to discuss his recent article entitled: Anti-Stalin Falsehoods from a 'Socialist' Writer - refuting Alex Skopic’s article 'Stalin Will Never Be Redeemable.'” (links below). Dr. Furr is a professor, historian and author. Dr. Furr is a professor of Medieval English literature at Montclair State University. Dr. Furr is also renowned for his extensive research and writing on the Joseph Stalin period of Soviet history. In fact, Dr. Furr has published well over a dozen books and published countless articles on this period. |

* * * * *

In the wake of Stalin’s death in 1953, the floodgates of state censorship opened, and a seemingly endless series of atrocity stories came out—but some socialists, both in the USSR and the West, simply refused to believe them …

Today we know that those who refused to believe Khrushchev’s talks of Stalin’s supposed “crimes” were correct! They “smelled a rat.”

Khrushchev and his followers produced no evidence to support their accusations. The striking lack of primary-source evidence is what started me on my quest for the truth about Stalin and the Stalin-era Soviet Union years ago.

We Must Defend Not Stalin, But the Truth

Skopic writes:

These are, broadly speaking, the two rationales used by Stalin’s defenders today. Either the murderous nature of his regime was completely fabricated (the theme of Grover Furr’s signature book Khrushchev Lied) …

Skopic repeatedly accuses me of “defending Stalin” and calls me a “Stalinist.” But what is a “Stalinist”? Either it means someone who “defends” Stalin and “apologizes” for Stalin’s “crimes”, or it is simply a term of abuse, of dismissal.

I am not a “Stalinist.” I have been searching for decades for evidence that Stalin committed crimes. If Stalin committed crimes, I want to know about them. We all need to know about them – if they exist. But so far I have yet to find any evidence that Stalin committed even one crime! Every accusation of a crime by Stalin alleged by anyone from legitimated academic “experts” to people like Skopic is false.

Regardless of the evidence, this result is unacceptable, literally “taboo” to anticommunists and Trotskyists, academics included. The most renowned and respectable academic authorities such as Stephen Kotkin of Princeton and Timothy Snyder of Yale have lied and falsified dozens, if not hundreds, of times, rather than accept the results that flow from the study of primary-source evidence about Stalin.

I call this the “Anti-Stalin Paradigm”, or ASP. All academic research on Stalin must confirm to this ASP or it will not be published. That would doom the career of any scholar hoping to teach Soviet history. So, the evidence is ignored and lies and falsehoods, many of them obvious to those who repeat them, are recycled, or, in some cases, new lies and falsehoods are invented.

Stalin and his propagandists never missed a chance to slam the United States for its record on racial injustice, deploying the bitter phrase “А у вас негров линчуют” (“And you are lynching Negroes!”) whenever American diplomats criticized the USSR’s human rights abuses. This was, of course, a cynical ploy …

“Whenever” implies repeated action. Yet Skopic does not cite a single instance of this (I cannot find any either). “Cynical plot” implies – without evidence – that Stalin and the Soviet leadership were not really opposed to racism.

Skopic admits that Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, and other Black Americans found the dedication to anti-racism in the USSR inspiring. So how could Skopic possibly know that Stalin’s anti-racism was really “a cynical ploy”? He can’t!

Skopic Confuses “Sources” With Evidence

The Stalinists of the 20th century desperately wanted to believe in the promise of a new society, and they weren’t given the facts they needed to see through the illusion. In the 21st century, though, we have no such excuse. There is ample evidence from dozens of different sources detailing Stalin’s abuses and betrayals …

This illustrates one of Skopic’s central errors: he confuses “source” with “evidence.” A “source” is just where you found some statement or other, regardless of whether that statement is true or false. Primary-source evidence, usually in documentary form, is the only valid basis for truthful conclusions. Skopic has no primary-source evidence of any “abuses” or “betrayals” on Stalin’s part – only fact-claims from anticommunist and Trotskyist writers who themselves have no evidence.

… with the single exception of Hitler—he was the most lethal anticommunist of his time. In fact, the epitaph of virtually every prominent European socialist to die in the years 1928-1945 reads either “murdered by Hitler” or “murdered by Stalin.”

If there were so many, why doesn’t Skopic name even one of them? Since he cites no names, no one can check to see whether Skopic is telling the truth or not.

Skopic:

Soon after he was named General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1922, Stalin began maneuvering against the other Bolshevik leaders who had organized the October Revolution, packing important positions with his own supporters …

Skopic fails to cite even one example. I have never found any either.

Leon Trotsky made this accusation, also without evidence. Trotsky is probably Skopic’s unnamed source here. Trotsky is the source of a great many false allegations against Stalin of crimes and misdeeds.

and arranging various smears and frame-ups against his rivals.

Again, Skopic cites no examples. There is no evidence to support this allegation.

Skopic:

Leon Trotsky, the leader of the Left Opposition faction, was ejected from the Party in 1927 after he refused to abandon the idea of global revolution (which Stalin opposed) …

False. This is another of Trotsky’s slanders. Stalin did not oppose “global revolution” at all.

In his preface to Stalin’s Letters to Molotov (1996) Robert C. Tucker, an anti-Stalin historian at Princeton University, wrote::

[Lars] Lih raises the question: Did Stalin dismiss world revolution in favor of building up the Soviet state (as Trotsky, for one, alleged at the time), or did he remain dedicated to world revolution? Lib's answer, based on the letters, is that in Stalin's mind the Soviet state and international revolution coalesced, and the letters provide support for this view. (ix)

Lars Lih, the editor of this volume, writes:

Stalin's intense involvement belies the image of an isolationist leader interested only in “socialism in one country.” The letters show us that Stalin did not make a rigid distinction between the interests of world revolution and the interests of the Soviet state: both concerns are continually present in his outlook. (5-6)

Skopic:

… by 1929 he [Trotsky] had been exiled from the USSR altogether, and in 1940 Stalin had him assassinated.

Aren’t the reasons relevant? Of course, they are! But Skopic omits them.

Trotsky was exiled because he repeatedly formed a fraction within the Party after Party fractions had been outlawed at Lenin’s insistence in 1921. Even before Lenin died in January 1924 Trotsky and his followers were actively organizing against the Party. Trotsky was expelled after the opposition organized a counterdemonstration on the tenth anniversary of the Revolution in October, 1927.

Many of his fellow conspirators recanted and promised to be good Party members from then on. It turned out later that some of them were lying and continued to conspire in secret.

But Trotsky refused to recant. Exiled in comfortable conditions to Alma-Ata in the Kazakh SSR – he was able to carry on a wide correspondence and even to go hunting -- Trotsky continued his factional organizing. At length the Party leadership decided to expel him to Turkey, where they arranged a large house for him to stay on a Turkish island.

Trotsky was assassinated in August 1940, probably by Stalin’s order. The general reason was that Trotsky had conspired with Nazi Germany and militarist-fascist Japan to aid them against the Soviet army in the event they attacked the USSR. The proximate reason, according to General Pavel Sudoplatov, was that Stalin believed that Trotsky’s followers would weaken international support for the USSR when war broke out.

“There are no important political figures in the Trotskyite movement except Trotsky himself. If Trotsky is finished the threat will be eliminated,” Stalin said.

Skopic:

Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, close associates of Lenin who were originally supposed to rule with Stalin in a triumvirate, were accused of the murder of Sergei Kirov (for which some historians believe Stalin was also responsible) and summarily executed in 1936.…

False. Zinoviev and Kamenev led a clandestine terrorist group of “Zinovievists” (Party members and former members loyal to Zinoviev when he was head of the Party in Leningrad) whose Leningrad branch murdered Leningrad Party leader Sergei Kirov, who had replaced Zinoviev. We have a great deal of evidence about their activities. I have carefully studied the evidence against the Leningrad Zinovievists.

In 1935 Zinoviev and Kamenev were tried and sentenced to prison terms. At that time the NKVD stated that there was no evidence that Zinoviev and Kamenev themselves had been involved in Kirov’s murder.

However, by mid-1936 some members of the Zinovievist conspiratorial group had accused Zinoviev and Kamenev of complicity in Kirov’s murder. They confessed inJuly 1936. I have put online a translation of Zinoviev’s confession of August 10, 1936.

The First Moscow Trial was quickly organized in August. Zinoviev and Kamenev repeated these confessions at trial and were sentenced to death. In their appeals to the court for clemency, which were never intended for publication, Zinoviev and Kamenev repeated their guilt. Therefore, it is a lie to say that Zinoviev and Kamenev were “summarily executed.”

Not even mainstream anticommunist historians “believe” that Stalin was involved in Kirov’s death. So where did Skopic get this – what was his “source”? Most important: since “belief” is irrelevant, what is Skopic’s evidence that Stalin was involved? He has none, because no such evidence exists.

Skopic:

With each year, the accusations of treachery grew wilder, and the evidence thinner, often relying entirely on confessions extracted under torture.

There is no evidence of either of“thin” evidence or of confessions “extracted under torture” in the Moscow Trials. No wonder Skopic does not cite even one example! (For Nikolai Yezhov’s illegal crimes, see below).

Skopic:

Trials became farces lasting as little as 15 or 20 minutes.

Trials at which the defendant confesses his guilt, and the court has evidence to confirm it, were often short, as they are in the United States today when an accused confesses guilt before a judge. However, in the next sentence Skopic mentions Nikolai Bukharin. Bukharin was a defendant in the Third Moscow Trial of March 1938, a public trial that lasted twelve days, from March 2 to March 13.

Skopic:

Nikolai Bukharin, leader of the moderate Right Opposition, managed to survive until 1938, but in the end he, too, was sentenced to death for his supposed involvement in a Trotskyist and/or Nazi conspiracy…

There is no excuse for this falsehood. The transcript of the 1938 Trial in which Bukharin was convicted was published in 1938. Several of Bukharin’s pre-trial confessions have been available for years.

At trial Bukharin confessed to some serious crimes while stubbornly refusing to confess to others. A differentiated confession like this suggests that the confession of guilt was genuine. It certainly proves that Bukharin was not threatened with torture or mistreatment of his family.

Skopic continues:

Bukharin’s last message is particularly haunting, using Stalin’s personal nickname in

an appeal to their onetime friendship: Koba, why do you need me to die?

Years ago, my colleague Vladimir Bobrov and I published an article in which we proved that this is a fake. See Furr and Bobrov, “Bukharin's Last Plea: Yet Another Anti-Stalin Falsification.” This article has been available online, in English, since 2010! Couldn’t Skopic have done a Google search?

Skopic:

In the same year, Jānis Rudzutaks, a Latvian revolutionary who had served ten years in Tsarist prisons for his Bolshevik convictions, was executed despite never having voiced the slightest objection to the Party line.

Conspirators always “voiced” agreement with the Party’s position in order to mask their conspiracy.

His [Rudzutak’s] only offense, according to Stalin’s confidante Vyacheslav Molotov, was that he was “too easygoing about the opposition” and “indulged too much in partying with philistine friends,” and was therefore a liability.

Molotov did not say that this was Rudzutak’s “only” offense. Why did Skopic tell this lie? Moreover, in 1938 Molotov had his hands full as head of state – Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars. How would he remember, in extreme old age, what the specific accusations and evidence against Rudzutak had been?

Today we have a great deal of evidence against Rudzutak. His NKVD investigation file has long been available to researchers. It contains Rudzutak’s confessions along with much other evidence against him.

Rudzutak was also accused by several defendants at the Third Moscow Trial of 1938. In lengthy statements to the court defendant Nikolai N. Krestinsky named Rudzutak as a conspirator many times. The trial transcript has been available since 1938. Why didn’t Skopic consult it?

Skopic:

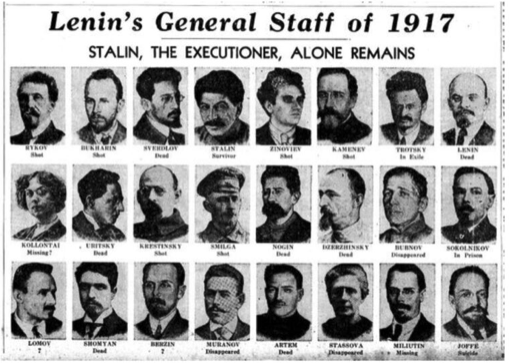

As it happens, I have written an article in which I examine this very document (Socialist Appeal was a Trotskyist newspaper). It will be published in a future book. For now let me note that this list was dishonest -- intended to deceive -- when it was published in 1938.

* Eight of the figures whose photos appear in the “gallery” -- Uritsky, Shaumian (not “Shomyan”), Sverdlov, Artem (Sergeev), Lenin, Nogin, Dzerzhinsky, and Ioffe -- were indeed dead by 1938. Stalin had nothing to do with their deaths.

What's the point of including so many people who had died by 1938 except to imply, without evidence, that Stalin was in some way responsible for their deaths?

* Three more lived long after 1938. Alexandra M. Kollontai died on March 9, 1952. Matvei K. Muranov died on December 9, 1959. Elena D. Stasova died on December 31, 1966.

This is a dishonest propaganda technique. It has nothing to do with understanding history. Yet this kind of duplicity characterizes most anticommunist and Trotskyite writing on the Stalin period up to the present day.

In my article I examine the evidence against the eleven, all men, who were indeed executed. Every one of them was convicted at a trial where much evidence against them was produced. In many cases the accused confessed. It is absurd to claim that a person who repeatedly confesses his guilt and is impeached by the testimony of others is nevertheless“innocent.”

Skopic:

With characteristic chutzpah, Grover Furr attempts to justify the purges in Khrushchev Lied, asserting that all of the above really were spies and saboteurs, but the numbers are against him …

I must protest Skopic’s dishonesty here. Most readers of Skopic’s article will not have read my book Khrushchev Lied (2011) or will not have read it recently, and so will not know that his statement here about my research is false.

* I do not discuss “all of the above” in my book Khrushchev Lied.

* I do not assert that “all of the above” were guilty. Indeed, I do not claim that any of the persons named by Khrushchev as innocent victims of Stalin were guilty.

What I do in that book, as in all my other books, is examine the evidence that we now have. In the cases I have examined there is plenty of evidence of the guilt of the people under discussion and no evidence that they were innocent.

Skopic clearly does not understand historical research, so a word about that is relevant here. It is not the job of a historian to assert the guilt or the innocence of anybody. The historian’s duty is to identify, locate, obtain, and examine the evidence and, where possible, to draw logical conclusions from that evidence.

A historian must always be prepared to modify or even reverse his original conclusion if and when more evidence comes to light and demands it, or a more convincing interpretation of the currently available evidence is produced.

Skopic:

… What are the odds, after all, that essentially everyone but Stalin suddenly turned traitor, leaving him the only stalwart?

This is just nonsense. Thousands of “old Bolsheviks” (persons who had joined the Party before the Revolution) and other Party leaders remained. Khrushchev named only a small number of persons whom he wished to“rehabilitate” – that is, to declare innocent while never producing evidence that they were, in fact, innocent. In my book Khrushchev Lied I examine only those whom Khrushchev names in his “Secret Speech” of February 25, 1956.

Skopic:

With each new show trial, a ripple effect ran through Soviet society, as anyone who was tainted by association with the “guilty” party—from their family members to people who were merely seen talking to them or reading their books—stood a decent chance of being arrested, executed, or deported to Siberia in turn.

These statements are false. Skopic gives no examples of even a single person to whom any of this happened. And no wonder! I have never found an example of anyone who was executed or deported to Siberia simply because they were “merely seen talking to” or “reading the books” of a convicted person. Not one!

Wives of high-ranking Party and military figures who had been convicted of serious crimes like espionage or sabotage were imprisoned or exiled, on the assumption that they must have known something about their husband’s activities yet did not report them. In some cases, we have evidence that the wife was also guilty.

In other cases, we have no such evidence, although it may still be in former Soviet archives. It is possible that some wives who had been kept in the dark about their husband’s conspiratorial activities were imprisoned. But we don’t have the evidence so we cannot tell whether this occurred or not.

I have never found even one example of a person in any of the categories named here by Skopic who was executed, and Skopic does not cite even a single example.

“Quotas”?

Skopic:

Like American cops today, Stalin’s secret police worked on a quota system, in which officers were required to make a certain number of arrests per month …

This is false. American historian Arch Getty has refuted this “quota system” notion several times.

One of the mysteries of the field [of Soviet history — GF] is how limity [“limits”] is routinely translated as “quotas.”

For more about this specific lie see my book Stalin Waiting for … the Truth, Chapter Ten, “The Falsehood About ‘Quotas’”.

Anticommunist “scholars” continue to lie, claiming that Stalin had “quotas” for arrests. Obviously they want him to have had quotas so they can condemn him!

We must ask: If you need to invent spurious crimes in order to find reasons to condemn Stalin, doesn’t that imply that you could not find any real crimes of which Stalin was guilty? For if you could find real crimes, why not just discuss them without inventing phony ones?

Skopic:

In a typical case, one unlucky woman was arrested as a Trotskyist, then had her charge changed to “bourgeois nationalism,” on the grounds that the local NKVD had “exceeded4 the quota for Trotskyites, but were short on nationalists, even though they’d taken all the Tatar writers they could think of.”

The quotation is from Robert Conquest, The Great Terror. In the revised edition the quotation is on page 284. The reference there is to Evgeniia Ginzburg, Journey into the Whirlwind, page 105, and this passage is indeed in Ginzburg’s book.

Abuses of this kind, and on a massive scale, were committed by Nikolai Yezhov’s men during the time he was head of the NKVD. But we have no way of verifying what Ginzburg wrote here. She was fiercely anti-Stalin, believed the Khrushchev-era lies about Stalin, and had little motive to be objective.

Ginzburg was arrested in February 1937, on the testimony of some of her co-workers, in the immediate aftermath of the Second Moscow Trial or “Trotskyist” trial of January 16 - 30, 1937. She was accused of being a member of a clandestine Trotskyist group. We have plenty of evidence that such groups did exist.

Ginzburg claims that she was innocent. But we really do not know. It is common for both the guilty and the innocent to claim innocence. The fact that she was “rehabilitated” does not prove that she was innocent because many persons were “rehabilitated” during the Khrushchev and Gorbachev eras without any evidence that they were in fact innocent.

I have examined a number of such cases in Chapter 11 of Khrushchev Lied.In some cases, like that of Bukharin, we know that the Soviet prosecutor and judges falsified evidence in order to declare him innocent.

In the early 1990s two NKVD investigative reports of her case were published. These reports detail the testimony against Ginzburg from co-workers. On the basis of this evidence, she was convicted and sentenced first to prison and later to a labor camp.

The “Yezhovshchina”

In late July or early August 1937, Nikolai Yezhov, chief (“People’s Commissar”) of the Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD), which included the political police that are often called “the NKVD,” began a 14-month orgy of mass arrests and executions. Most persons executed must have been innocent, as Yezhov and his men testified in 1939 when, after replacing Yezhov as head of the NKVD, Lavrentii Beria began to investigate these massive illegal repressions.

Primary-source documents from former Soviet archives prove that Yezhov deceived Stalin and his leadership in order to further his own conspiracy. As I conclude in my book about this period, Yezhov vs Stalin,

The version set forth here absolves Stalin of guilt for the massive repressions. This is what is unacceptable to mainstream Soviet history. But it was certainly Stalin’s responsibility, as the principle political leader of the country, to take decisive action to stop violations of justice, have them investigated, and make sure those responsible are punished. Stalin did this. Tragically, it took him many months to fully realize what was really going on, by which time Ezhov and his men had murdered hundreds of thousands of innocent Soviet citizens. (231)

On January 2, 1939, Stalin wrote Prosecutor Vyshinsky: “A public trial of the guilty parties in the NKVD is essential.” Such public trials did not take place. We do not know why. However, there were many non-public trials of Yezhov’s NKVD men, including of Yezhov himself. Many were sentenced to death for their crimes. During the first year after he took office, Beria released at least 110,000 prisoners from the camps (“GULAG”) and prisons.

During the same year [1939] about 110,000 persons were freed after the review of cases of those arrested in 1937-1938.

Lavrentii Beria

Skopic:

Later, others fell victim to the sadism of Lavrentii Beria, a truly vile figure who used his position as head of the secret police to sexually assault hundreds of women and girls, often threatening a loved one under arrest to secure their silence.

These are lies. Skopic cites no evidence. And no wonder! There has never been any good evidence that Beria carried out these sexual assaults.

An article in a conservative Moscow newspaper contains the following passage:

One of the experts who had the opportunity to study the cases of Beria and the head of Stalin's security, General Vlasik, classified to this day, discovered an extremely interesting fact. The lists of women in whose rape, judging by the materials of his case, Beria pleaded guilty, almost completely coincide with the lists of those ladies with whom Vlasik, who was arrested long before Beria, was accused of having relations.

On June 26, 1953, Beria was either arrested or – as it increasingly appears – killed in the act of being arrested, at a Presidium meeting by his colleagues in the leadership of the CPSU. Beria was not present at the Central Committee meeting in July 1953, called for the sole purpose of slandering him. Why not? This was unprecedented for such a high-ranking official – a minister in the government.

Beria was allegedly tried, convicted, and executed at a trial in December 1953. But no trial transcript has ever come to light. A lot of evidence that Beria was murdered at this time or possibly shortly thereafter has been published. Some of it is summarized in a recent study by two Russian historians.

Concerning the conduct of the trial of “Beria” – supposedly present but probably already murdered – and his associates, Colonel-General Aleksandr F. Katusev, Chief Prosecutor of the USSR from 1989 to 1991, during the time of Gorbachev, has written:

Считаю своим долгом отметить, что вновь открывшиеся обстоятельства лишь дополнительно высветили ошибки и натяжки в приговоре по делу Берии и других. В то время как наиболее серьезные из них были очевидны и прежде. Чем же объяснить, что крупнейшие наши юристы под руководством Руденко Р.А. предъявили обвинение, не подкрепленное надлежащими доказательствами.

Ответ лежит на поверхности. Еще до начала следствия были обнародованы постановления июльского (1953) Пленума ЦК КПСС и Указ Президиума Верховного Совета СССР, в которых содержалась не только политическая, но и правовая оценка содеянного»..\

I consider it my duty to note that the newly discovered circumstances only additionally highlighted the errors and exaggerations in the verdict in the case of Beria and others, while the most serious of them were obvious before. How can we explain that our most prominent jurists, under the leadership of Roman A. Rudenko, could have made these charges without proper evidence?

The answer is obvious. Even before the start of the investigation, the resolutions of the July (1953) Plenum of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR were made public, which contained not only a political, but also a legal assessment of the deed.

Katusev stated that there was no proper evidence against Beria and the others, and they were accused, convicted, and executed on the basis of the Central Committee Plenum of July 1953 and a decree of the legislature! If, in fact, a transcript and materials of the “Beria trial” of December 1953 exist, Katusev would have had access to them. He does not mention any transcript. This might mean that there is none and no trial really took place. But to draw this conclusion would be an argumentum ex silentio and in this case a logical fallacy.

Skopic continues about Beria:

This statement is contradicted by the very source Skopic cites, a 1993 article in the British newspaper Independent. That article states:

MOSCOW - Building workers digging a ditch in the centre of the city on Friday unearthed a common grave near the mansion once occupied by Stalin's secret police chief, Lavrenti Beria, writes Helen Womack. Since Beria was notorious for carrying out interrogation and torture in his own home, it is reasonable to assume that the bones are the remains of his personal victims.

… it is believed that Beria lured young women there, had sex with them, then had them murdered in the basement.

… The workers had been digging for several hours when they came upon a pile of human bones, including two children's skulls …

So not “at his former home” as Skopic claims but “near” it, plus” children’s skulls.” Was Beria raping children too, and then carrying the remains outside his home to bury them “near” where he lived? Ridiculous!

There is no evidence that these bodies had anything to do with Beria. So why did Skopic distort what the article says? Is he “grasping at a straw” – trying to find something that will make Beria look bad? It sure looks that way.

Executions

Skopic:

Even if we grant the most pro-Stalin interpretation of the facts, counting only the deaths directly recorded in the Soviet archives (799,455 executions, 1.7 million deaths while imprisoned, 390,000 during the forced resettlement of rural peasants, and 400,000 people deported to Siberia and elsewhere), we still get a figure of more than three million.

The source normally cited for numbers of executions from 1921-1953 is Viktor Zemskov, “Pravda o repressiiakh” (The truth about the repressions), 2009, republished several times on the internet.

I quote from one of my essays:

In September 1936 Nikolai Ezhov replaced Genrikh Iagoda as head (Peoples Commissar) of the NKVD. In November 1938 Ezhov was replaced by Lavrentii Beria. According to the widely publicized “Pavlov report” prepared for Khrushchev in 1953 and widely reprinted the number of persons sentenced to death in 1936-1940 were as follows: [6]

1936 – 1,118

1937 – 353,074

1938 – 328,618

1939 – 2,552

1940 – 1,649

In 1939 death sentences under Beria were less than 1% of those under Ezhov. In 1940 they were less than ½ of 1%. No mass political repression occurred during Stalin’s postwar years. The “Ezhovshchina” (=“bad time of Ezhov”) was never repeated. The conclusion is inescapable: It was not Khrushchev, but Stalin and Beria who ended mass political repression, and they did it in late 1938.

Executions during these six years out of 32 ½ years equal 745,523, or 93.3% of the total of 799,455. Executions during 1937 and 1938, the two years of Yezhov’s mass illegal murders, total 85.3% of the total of 799,455.

For more detailed discussion of Yezhov’s conspiracy and his mass murder of innocent Soviet citizens, Beria’s investigations of Yezhov and his men, and a great deal of primary-source evidence--almost completely ignored by mainstream anti-Stalin historians -- see Yezhov vs Stalin.

Deaths in the GULAG

The source used by professional researchers, most of whom are anticommunist and strongly biased against Stalin, is GULAG. (Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei), 1918-1960. (Moscow: MDF, 2000), edited by Kokurin and Petrov of the anticommunist “Memorial” Society. Document No. 103 of this work gives the mortality in the GULAGcamps by year. It can be viewed online as a table. This shows that the higher mortality rates were in 1932 (13,197 or 4.8%),1933 (67,297 or 15.3%), 1942 (352,560 or 24.9 %) and 1943 (267,826 or 22.4 %). The next highest year, 1944, saw a 9.2% mortality, higher than all the remaining years.

Of the total number of deaths in the GULAG from 1930 (the first year we have statistics) till 1953 (Stalin died on March 5 of that year), we get 1,590,384 deaths in the GULAG between 1930 and 1953. Of these deaths, 43.2% of them or 687,683 occurred in the three years 1933, 1942, and 1943. 1932-33 were the years of the great famine of ’32-’33 when mortality was very high throughout the USSR.1942 and 1943 were the worst years of the war. 50.7% of all the deaths in the GULAG occurred in 1932-33 and 1942-44.

During these periods a great many Soviet citizens were also dying prematurely. For example: during World War II Soviet workers sickened and died of starvation at their work, far from any fighting. (Editor's Note: Indeed, many people died, including notable figures, like Oleg Losev, the inventor of the LED, as even the Wikipedia recognizes: Losev died of starvation in 1942, at the age of 38, along with many other civilians, during the Siege of Leningrad by the Germans during World War 2.[1][2][3] It is not known where he was buried.)

The high intensity of work at the factory and the inadequacy of the food make it a matter of urgency that [workers receive their rightful days off], as witnessed by the frequency with which workers are dropping dead from emaciation right on the job. On some days you see several corpses in the shops. During the two months December 1942 and January 1943, they observed 16 bodies just in the factory shops. Those dying from emaciation are mainly workers doing manual labor. (Shliaev, Chief Prosecutor of Cheliabinsk province, to Bochkov, Prosecutor General of the USSR, March 29, 1943)

This is from an article by Donald Filtzer, “Starvation Mortality in Soviet Home Front Industrial Regions During World War II.” Filtzer is a conventionally anticommunist scholar who specializes in studying the Soviet working class. He states:

During 1943 and 1944, starvation and tuberculosis – a disease that was endemic to the USSR and is highly sensitive to acute malnutrition – were between them the largest single cause of death among the nonchild civilian population.

Filtzer continues:

The USSR did not have enough food to feed both its military and its civilians, even with the arrival of Lend-Lease food aid. The state therefore had to engage in a grim calculus and decide how it could most efficiently use its limited resources – that is, how many calories and grams of protein it could allocate to different groups. In these circumstances it was inevitable that some people would not obtain enough to eat and many would die. No matter what regime had been in power in the USSR—Stalinist, Trotskyist, Menshevik, or capitalist—it would have faced the same set of choices.

Skopic does not identify his source for the figure of 390,000 persons dying during “forced resettlement of rural peasants” so it is impossible to know exactly what he means. It probably means that peasants – mainly rich peasants, or kulaks, and those who, perhaps under the influence of the kulaks, who were very influential people in their communities, resisted collectivization, were resettled, and eventually died, not during resettlement but at their place of resettlement. No doubt many of them died during the great famine of 1932-33 and the very bad famine of 1946.

Similarly, Skopic does not tell us where he gets the number of 400,000 “people deported to Siberia and elsewhere” or what it means – deaths during deportations, or all deaths, including persons who died after deportation.

We do have some information about mortality during deportations. For example, we know that very few of the Chechens and Crimean Tatars deported in 1944 for collaboration with the Germans died during deportation.

According to an NKVD report reproduced in several places, 191, or 0.126%, of the 151,529 Crimean Tatars deported to Uzbekistan, died in transit. … In the case of the much larger population of deported Chechens and Ingush, numbering 493,269 persons, we have primary source evidence that 1272, or 0.25%, died in transport.See N.F. Bugai and A.M. Gonov. “The Forced Evacuation of the Chechens and the Ingush.” Russian Studies in History. vol. 41, no. 2, Fall 2002, p. 56.

The Crimean Tatars and Chechens were deported en masse so as to keep these linguistically and culturally distinct groups united. To separate them would have been a form of genocide (though the term did not exist until after the war).

Skopic:

Under Stalin’s leadership, many of the hard-won victories of 1917 were undermined and rolled back, in a downward slide into social and political conservatism.

This was Leon Trotsky’s claim, so it is no surprise that Skopic quotes the following passage from Leon Sedov’s Red Book on the Moscow Trials (1936)

We’ll examine these assertions one at a time.

Revolutionary internationalism gives way to the cult of the fatherland in the strictest sense.

It was the whole Soviet Union, not just the communists, that the fascists would attack. But only a small percentage of Soviet citizens were communists. Non-communists, the vast majority of the population, were encouraged to be loyal to their country, the Soviet Union. Furthermore, since the Soviet Union was the homeland of socialism and the headquarters of the worldwide communist movement, why shouldn’t communists too be loyal to it?

Officers’ ranks were indeed re-established in the belief that this was necessary for a strong army. Red Army officers had been trained along the lines of, and in many cases by, military men from Western capitalist countries. Sharp differentials in wages for more productive work, as in the Stakhanovite movement, and “one-man management” for managers, were believed to be necessary for higher productivity.

These measures contradicted the move towards egalitarianism, a hallmark of development towards a communist society. But the Soviet Union was not even fully “socialist” yet. If the fascists defeated it they would never see either socialism or communism.

So, Stalin and the Party compromised on principle in order to move towards communism later, after defeating the fascists. Stalin did begin to do this after the war. But his efforts were cut shot by his death. For more on Stalin’s post-war efforts to move towards communism see Part II of my essay “Stalin and the Struggle for Democratic Reform.”

Sedov / Skopic:

The old communist workers are pushed into the background …

There is no evidence for this, or even an explanation of what it means. Who were these “old communist workers”? Since this was written by Sedov, Leon Trotsky’s son and closest political confidant, it probably means that workers loyal to Trotsky were no longer promoted within the Party or the trade unions. Naturally enough – Trotsky’s followers within the USSR were involved in serious anti-Party and anti-Soviet conspiracies.

Sedov / Skopic:

The old petit-bourgeois family is being reestablished and idealized in the most middle-class way …

This is incoherent. When was the family ever disestablished? Skopic does not tell us. But see comments on “socialism” below.

… abortions are prohibited, which, given the difficult material conditions and the primitive state of culture and hygiene, means the enslavement of women, that is, the return to pre-October times.

Abortion on demand was made illegal -- see the more detailed discussion below. However, the benefits granted to mothers shows that Skopic is wrong -- there was no “return to pre-October times.”

The “Trotsky Cult”

Trotsky hated Stalin. He had no incentive to be objective or truthful about Stalin and Soviet society of his day. In my books I have shown in detail that Trotsky lied about Stalin too many times to count. If Skopic doesn’t know this he has no business writing about the Stalin-era Soviet Union at all.

Skopic himself admits that “there are layers of irony to this passage” from Sedov’s book. Why then does he quote from it? Critical of the “great man” cult around Stalin – rightly so – Skopic has fallen prey to the “great man cult” around Trotsky!

The Stalin “cult of personality” thankfully died decades ago. Stalin himself strongly opposed it, as I have shown in Khrushchev Lied. But the “Trotsky cult” lives on, nourished by the falsehoods of overtly anticommunist historians and an uncritical attitude towards Trotsky’s own writings. I have published four books in which I show that Trotsky lied to an extent scarcely believable, especially about Stalin and anything to do with him.

Trotsky incited his clandestine supporters to assassinate Soviet leaders and sabotage the economy, conspired with Marshal Tukhachevsky and other high-ranking military commanders to sabotage the Red Army and with Nazi Germany and fascist Japan to stab the army in the back in the event of invasion. Trotsky agreed to abolish the Communist International, and to divide up the country to give Ukraine to Germany and the Pacific coast to Japan. Some communist!

Skopic:

… the working class found itself increasingly micromanaged and exploited under Stalin.

Skopic does not know what “exploitation” means. It is the private appropriation of the surplus value produced by the working class. Nothing of the kind occurred in the Soviet Union during Stalin’s time. Salary differentials between managers and workers, whether desirable, necessary, or not, are not “exploitation.”

Skopic:

… new labor-discipline laws introduced in 1938 and 1940 made it a criminal offense to be more than 20 minutes late to work, punishable by dismissal at minimum and sometimes actual imprisonment.

By 1938 the Soviet Union was preparing for the inevitable war that Stalin, with uncanny accuracy, had predicted in 1931 would happen in ten years.

We are 50 or 100 years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in 10 years. Either we do it, or we shall go under.

Military men were drafted and then subject to discipline. Why should workers, whose production would be a make-or-break matter in the upcoming war, be permitted to be absent or to move to try for a better job somewhere else? Production for the social welfare took precedence over the individual desire to “get ahead.”

Skopic:

The hated “domestic passports” used by the Tsars were reintroduced, forcing workers to show their “papers” to police at a moment’s notice, and justify why they were in a given area. If they couldn’t, this too could lead to arrest and prison time.

Passports were instituted, but not like under the Tsars. Pre-Soviet Russia was indeed an exploitative society. In the Soviet Union there was no appropriation of the value produced by the working class to private capitalists. All production benefited the working class as a whole.

The Soviet Union ran on a planned economy, not a market-based capitalist economy. Unlike in the capitalist world, jobs were guaranteed. But moving around to get the best job sabotaged the economic plan and production, so it was restricted.

Passports were also needed to control the movement of population, particularly to prevent a flood of immigration to the big cities. It was essential to develop the trans-Ural USSR, the Asian areas and Siberia, and to guarantee sufficient labor power on the collective farms that fed the whole society..

Skopic:

The government even resorted to strikebreaking and the suppression of labor power, arresting workers en masse in the cotton-mill town of Teikovo when they organized a short-lived strike against food rationing.

The state had an economic plan for the allocation of scarce resources. The plan called for shared scarcity. It was not an attempt at super-exploitation to make a rich boss even richer, as under capitalism.

The Teikovo strike and a few others were indeed protests against an increase in food prices. This was 1932, when industrialization was just beginning, collectivization was still under way, and the economy was very fragile.

Bolshevism had offered a promise of total liberation for working people, but now, Stalinism delivered the opposite.

Skopic has a bourgeois – i.e., a capitalist – idea of liberation.

The working class in the Stalin-era Soviet Union was indeed liberated from exploitation of worker-produced value by private capitalists. However, communist liberation cannot mean “freedom to do what you want, when you want.” Real liberation is only possible when there is a strong commitment to the collective good.

Skopic:

The point about “revolutionary internationalism,” too, deserves a closer look. At first glance, this might seem like an arcane Trotskyist grievance, but the consequences for people around the world were very real. To the extent that he believed in anything, Stalin was a firm believer in “socialism in one country”—that is, the idea that the Soviet Union should focus on its own industrial development, compete with the West on that basis, and remain detached from any form of global class struggle. The old slogan “workers of the world, unite!” was abandoned, and the Soviet state became either indifferent or actively hostile to the efforts of socialist movements in other countries, even as those movements looked to it for support and guidance.

This is simply a series of outright lies. Skopic has no evidence to support any of these allegations. Skopic has chosen to believe Leon Trotsky’s unsupported claim that building socialism in one country was in contradiction to building for revolution in other countries. This is not true (see the quotations from Robert Tucker and Lars Lih above).

During Stalin’s time the Communist International, or Comintern, was established in virtually every country in the world. The Soviet Union committed vast resources to supporting communist parties worldwide.

After Adolf Hitler smashed the Communist Party of Germany, the largest communist party in the world at that time outside of the Soviet Union, the Comintern saw that there was no chance for a socialist revolution any time soon in the industrialized countries of the world. It decided that fascism was the greatest danger to the world’s working class, so it downplayed organizing for communist revolution in order to try to make alliances with anti-fascist capitalist governments. Soviet and Comintern leaders were convinced that the USSR, the only country in the world that had no allies, could not defeat the impending fascist attack alone.

This strategy worked to a degree, in the sense that the Soviet Union managed to create an alliance with the major capitalist powers in World War II against the fascist powers. Victory against the Axis led to communist revolutions in China, Yugoslavia, Albania, and ultimately in Vietnam after the defeat of the United States.

The Soviet Union and the Comintern were also the principle forces behind anti-colonial struggles throughout the world. The Western imperialist countries of the so-called “Free World,” all of them self-styled “democracies,” never permitted democracy in their colonies, which they exploited with a murderous hand.

Soviet Aid to the Spanish Republic

Skopic:

In the Spanish Civil War, for example, the USSR lent a limited amount of military aid to the Republican forces battling Francisco Franco.

Skopic is in error. The USSR sent massive amounts of aid to Spain despite its own need to build up its military in advance of the inevitable war with the Axis.

The Soviet Union was generous in supplying military equipment to the Spanish Republic even though it was building up its own military as fast as possible too. On November 2, 1936, Kliment Voroshilov, Commissar for Defense, wrote to Stalin as follows:

Dear Koba! I am sending a letter of the property which, though it will hurt us, may be sold to the Spaniards... You will see that the list is for a rather substantial number of weapons. This can be explained not only by the great needs of the Spanish army and artillery, but also because Kulik (in my opinion, rightly) decided to finally free ourselves of some foreign-made artillery—British, French and Japanese—totaling 280 pieces, or 28% of the weapons of the category in our artillery parks. The most painful of all will be sending off the aircraft, but this is needed more than anything else, and therefore it must be given.

This private note, never intended for publication, proves Stalin’s commitment to proletarian internationalism in Spain.

The Spanish Republican government paid for some of this aid with gold. But the Soviets kept sending military equipment in 1938 and even in 1939, when there was no hope that the Republic could pay for it. Helen Graham, a world expert in the Spanish Civil War, has written:

… the Soviet Union actually also gave some big credits to the Republic in the course of 1938 which it must have known it would have absolutely NO chance of recouping (especially by the second half of that year) …

In her 2002 book The Spanish Republic at War 1936-1939 Graham writes:

In July [1938] [Prime Minister] Negrín sent his former ambassador to the Soviet Union, Marcelino Pascua (from spring 1938 ambassador in Paris) back to Moscow with the request. Stalin agreed to make a $60 million loan available to the Republic. This was in addition to the $70 million agreed the previous February. But this second loan was made when there was virtually no gold to back it. Without the July credit the Republican war effort could not have survived through the second half of 1938.

In The Spanish Civil War: A Very Short Introduction (2005) Graham writes:

In 1937 Soviet industrial production was still in a turmoil of reorganization, made worse by the purges, and throughout the war in Spain real Soviet production levels remained anything up to 50% below the published ones. Given this situation, it is surprising that Stalin sent even as much domestically produced materiel to the Republic as he did. This was high quality – most crucially the planes and tanks – and, as we have seen, it was vital to Republican survival, especially at the start. (88)

These scholars and documents give the lie to Skopic’s claim. In fact, the Soviet Union “gave even though it hurt.”

Skopic continues:

But at the same time, Stalin dictated the policy line of the Spanish Communist Party (Partido Comunista de España, or PCE), which was fiercely loyal to Moscow, and through this mouthpiece, he made it painfully clear that there would be no workers’ revolution as a result of the war. Instead, the PCE mandated a “united front” with a so-called “progressive bourgeoisie”—in other words, any part of the ruling class that wasn’t actively fascist …

The Soviets and the PCE believed that no workers’ and peasants’ revolution was possible as long as Nazi Germany and fascist Italy were arming and fighting alongside Francisco Franco’s army. Western powers feared a Bolshevik-type revolution in Spain much more than they feared Franco, a fellow capitalist and imperialist.

All the Spanish Republic’s governments were firmly capitalist. What they really wanted was aid from the non-fascist European powers, mainly Britain and France. They accepted Soviet aid because the Western powers, including the United States, refused them.

The hope of the Soviets and the Comintern was to defeat Franco, leaving the Spanish Republic as a liberal democracy with a strong and militant working-class movement and a large communist party. Then they could organize for revolution.

But this was exactly what the Western imperialist countries, together with the leaders of the Republican government, did not want. They much preferred a fascist, anticommunist, and capitalist Spain.

Understandably, many Spanish communists refused to follow these high-handed orders, especially in the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, or Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification—the other, non-Stalinist communist party in the mix). So, the Stalinists pressured the Republican government to declare the POUM an illegal organization, causing open conflict between the two factions.

This is false. Dominated by anti-Soviet Trotskyists, the POUM was one of the forces that led a rebellion – in fact, an abortive attempt at a revolution -- against the Spanish Republic while the war against Franco was going on. This 1937 revolt, called the “Barcelona May Days,” was a stab in the back of the Republic that had to draw resources from the anti-Franco war to suppress it.

Franco and Nazi agents were also working to bring about a split in the Republican forces that culminated in the “May Days’ revolt. The Soviets knew this from their agents. Trotsky had sent Erwin Wolf, his most trusted aide, to Spain, where he became a top adviser to POUM.POUM leader Andres Nin had also been a top political aide of Trotsky’s. Kurt Landau, another Trotskyist, was a POUM adviser too.

For more details and evidence see my article “Leon Trotsky and the Barcelona 'May Days' of 1937.”

Skopic:

As Jesús Hernández, a high-ranking member of the PCE, recalls in his memoirs, POUM founder Andreu Nin was captured by agents of Stalin’s NKVD, who tried to make him confess to being a fascist traitor …

Skopic goes on to quote from this former Spanish Communist who claims that Nin was tortured and then killed when he would not confess. But Jesús Hernández is not a reliable source.

According to Paul Preston, one of the greatest historians of the Spanish Civil War,

Unfortunately, Jesús Hernández fell into the clutches of Joaquín Gorkín and the Congress for Cultural Freedom.In consequence, his work was manipulated by Gorkín and, I believe, contains several falsifications.

Preston recommends a study by Herbert Southworth and another by Fernando Hernández Sánchez. Both question the objectivity of Jesús Hernández’s book.

Southworth:

According to Gorkin … José Bullejos, Secretary-General of the Spanish Communist Party from 1925 until his expulsion in 1932, informed him that Jesús Hernández wanted to talk with him. It was common knowledge among the Spanish groups in Paris that Gorkin could help to publish anti-Communist books. Gorkin, according to Gorkin, replied to Bullejos: ‘I cannot clasp the hand of Jesús Hernández so long as he has not denounced in a book the Stalinist crimes in Spain and, precisely, the details about the imprisonment and assassination of Andrés Nin’.

Gorkin, in effect, had indicated to Hernández the conditions under which his book could be published. ‘Six months later’, Gorkin continued, ‘after my return to Paris, I received the text of Hemández’s book ‘Yo fui un ministro de Stalin’. Hernández had followed the instructions given by Gorkin … (267)

[Gorkin’s book] contained … thirty pages from Jesús Hemández’s Yo fui un ministro de Stalin, the manuscript of which, as I have indicated above, was corrected following Gorkin’s instructions to overstate the significance of the murder of Andrés Nin, turning it into the pivotal incident of the Spanish Civil War. Unsurprisingly, these pages from Hernández’s opus gave exaggerated importance to the POUM and to the political role of Julián Gorkin. (290-1)

… since the CIA, and its affiliate the Congress [for Cultural Freedom – GF], grouped together, constituted a major world-wide influence for right-wing causes, its centralizing force ineluctably, however haphazardly, pulled into its orbit all those persons interested in besmirching the Spanish Republicans. Among the leading candidates for this kind of work were Julián Gorkin and Burnett Bolloten. (307)

Hernández Sánchez doubts that Jesús Hernández simply followed Gorkin’s hints in order to get his book published. But he does not deny that the Congress for Cultural Freedom, a front of the American C.I.A., was involved in publishing his book. No genuine communist would accept support from such a source. Hernández Sánchez also records that Ricardo Miralles, a biography of Juan Negrin, questions the accuracy of Jesús Hernández’ book on several grounds.

No one claims that Jesús Hernández was a witness to Nin’s interrogation, so his account is hearsay in that regard. But the story of Nin’s arrest, supposed “torture,” and murder by communist and Republican police have become a mainstay of anticommunist historiography of the Spanish Republic.

There is no evidence that Nin was tortured. Paul Preston believes he was not.

Preston assumes here that Nin had no relation to the fifth column (Francoist forces within the Republic). It is more accurate to say that we don’t know whether he did or not. There is good evidence that Trotskyists and Germany and Francoist agents were both involved in the “May Days” revolt in Barcelona. (See my article for more details and documentation.)

Far from securing a united front, Stalin’s meddling had snuffed out any hope of resistance, and Spanish fascism reigned supreme.

No one has ever cited any evidence that a proletarian revolution could have been victorious in Spain in 1937, much less one led by an unstable coalition under anticommunist leadership, Trotskyist (POUM) and anarchist. Even George Orwell, whose Homage to Catalonia was a Cold War-anticommunist hit, later conceded that the Spanish Republic was doomed by the “democratic” Allies, who blockaded aid to the Republic while allowing Hitler and Mussolini to send enormous amounts of materiel, airmen, and soldiers, to aid Franco. In 1942, Orwell wrote:

Skopic recognizes that “nobody, not even the Yugoslav Communists, spoke of revolution.” But Skopic knows better! Sure, he does! So, he still blames Stalin for the fact that

it took until 1945 for Yugoslavia to actually become a socialist nation—a much longer and bloodier struggle than it might have been.

No one believed that socialist revolution was possible while a country, whether Yugoslavia or Spain, was occupied by Hitler’s army. Yugoslav partisans were not able to expel German troops until 1945. They could only do it then because three-quarters of Hitler’s army was fighting the Red Army. This was the help that “Stalin” (read: the Red Army and Soviet people) gave to make the revolution possible in Yugoslavia.

Skopic:

When Greek communists begged Stalin for help in their own civil war, their pleas fell on deaf ears. Stalin, it turned out, had promised to stay out of Greece and Turkey in a backroom deal he made with Churchill, in exchange for greater influence over the Balkans—and he valued his word to an arch-imperialist more than the lives of the Greek partisans. Across the ocean, Harry Truman had no such qualms, and supplied the Greek far right with both military advisors and napalm. The revolution burned to ash.

Skopic falsely assumes that the Soviet Union had the capability of facilitating a revolution in Greece. But Stalin knew that the Red Army was not prepared for a war with the US and Great Britain. The Soviets were probably aware that within a month or so of the end of the war the Western capitalists were considering a joint Allied attack on Soviet forces in Europe – “Operation Unthinkable.” Stalin appears tohave also harbored an illusory hope that the USSR could maintain a peacetime Grand Alliance with the “Allies.”

Homophobia and Abortion

Skopic discusses the law of 1933 criminalizing homosexuality and the later law outlawing abortion on demand while permitting exceptions for medical reasons. What Skopic does not reveal is that the Soviet policy on (male) homosexuality was in accord with medical – that is, scientific – opinion in the advanced capitalist countries.

In the 1930s virtually all Soviet doctors had been trained before the Revolution. The few doctors trained after the Revolution had been educated by the older doctors. Soviet medical science followed that of the European capitalist countries.

It is idealism to fault the Bolsheviks for not somehow knowing that the best contemporary medical opinion was based more on age-old prejudice than on science. Homosexuality and abortion were not legalized in capitalist countries until 40 years later or more.

Skopic:

When the Scottish Marxist Harry Whyte, then working for the Moscow Daily News, wrote his own impassioned letter to Stalin defending gay rights, Stalin’s answer was blunt, scrawled across the letter in pencil: “An idiot and a degenerate.” (To the archives the letter went.)

But even Whyte himself expressed in this letter what we would regard today as prejudiced views about certain types of homosexuality:

When we analyze the nature of the persecution of homosexuals, we should keep in mind that there are two types of homosexuals: first, those who are the way they are from birth … second, there are homosexuals who had a normal sexual life but later became homosexuals, sometimes out of viciousness, sometimes out of economic considerations.

As for the second type, the question is decided relatively simply. People who become homosexuals by virtue of their depravity usually belong to the bourgeoisie, a number of whose members take to this way of life after they have sated themselves with all the forms of pleasure and perversity that are available in sexual relations with women.

Skopic:

The homophobic law remained on the books until 1993, and it decimated the Soviet LGBT community, sending thousands to the Gulag …

Skopic hasn’t even read the text of this law! It does not mention lesbian sex, bisexual persons, or transsexuals. Only sexual relations between men were illegal. Moreover, Skopic does not know how many people were imprisoned under this law. The article linked at this point in Skopic’s essay refers to the 1970s and 80s, not to the much-earlier Stalin period.

Abortion

Abortion on demand was made illegal -- as it was in capitalist societies at that time, and for the same reason: medical opinion opposed it (abortion for medical reasons was of course permitted).

Skopic mentions that the Soviet state provided “paid maternity leave and cash allowances for childcare supplies.” He comments that this Soviet provision of aid to mothers was more progressive even than many capitalist states today, much less at the time.

In today’s capitalist world, where increasing numbers of young people simply can’t afford to have children and are pressured to return immediately to work when they do, some of this might sound genuinely nice.

But then Skopic claims that being supportive to mothers was not Stalin’s intention:

But Stalin was less concerned with helping women or children as such, and more with replacing the devastating loss of population the USSR had suffered in the first World War (to say nothing of his own purges and manufactured famines).

Skopic is determined to portray Stalin in negative tones. But the text of the Soviet law (see below) goes far beyond anything in contemporary capitalist societies at the time.This law was clearly progressive for its time! So Skopic claims that Stalin did not support it for progressive reasons! Skopic cannot possibly know what Stalin’s intentions were – what he was “concerned with.”

Skopic refers to “manufactured famines” -- plural. But there were no “manufactured famines.” There were four famines in the USSR during the 1920s, all due to the devastation of war, disease, and natural causes. The great famine of 1932-33 was entirely due to natural causes. The last famine of Soviet times was in 1946, due to weather conditions that high Western Europe hard as well. I discuss Soviet famines and the research on them in the first two chapters of Blood Lies and the first chapter of Stalin Waiting for … the Truth.

Skopic also doesn’t know that a “purge”—”chistka” in Russian -- was a periodic process of verification of Party membership cards to make sure that Party members were active and not engaged in anything immoral or illegal. The penalty for failing the purge was expulsion from the Party, usually with a chance to reapply after a certain period.

Skopic quotes from a 1946 article by Soviet revolutionary and ambassador Alexandra Kollontai promoting motherhood for Soviet women. Famous for her feminism, Kollontai’s support for motherhood reflects the progressive opinion of that time.

Skopic then quotes from an account by Anna Akimovna Dubova, a Soviet woman who recalled her own illegal abortions. Dubova’s father was a kulak, and her parents were Old Believers who considered the Bolshevik Revolution to be the work of Antichrist. Her anticommunist background may help to explain why Dubova’s account contains an important falsehood (see below).

In the source from which Skopic got Dubova’s story she reveals that she had one child with her husband, who went off to war. Then she lived with another man who abandoned her. Then her husband returned, and she had another child. Later she married at least twice more, and had two abortions. She said:

… So many women died, leaving small children, and so many were sent to prison. Women who had the abortions and suffered were sent to prison, and those who performed the abortions were also sent to prison. …

This is not true. Women who had illegal abortions were not imprisoned. Dubova herself was not imprisoned. Either her memory failed her here, or she deliberately lied to make the Soviet policy appear worse.

The law reads in part:

4. В отношении беременных женщин, производящих аборт в нарушение указанного запрещения, установить как уголовное наказание, общественное порицание, а при повторном нарушении закона о запрещении абортов — штраф до 300 рублей.

4. With regard to pregnant women who have an abortion in violation of the said prohibition, to establish as a criminal punishment, public censure, and in case of repeated violation of the law on the prohibition of abortion - a fine of up to 300 rubles.

It’s worthwhile citing the title of the law (we won’t reproduce the text of the law in full – it’s too long):

Decree on the Prohibition of Abortions, the Improvement of Material Aid to Women in Childbirth, the Establishment of State Assistance to Parents of Large Families, and the Extension of the Network of Lying-in Homes, Nursery schools and Kindergartens, the Tightening-up of Criminal Punishment for the Non-payment of Alimony, and on Certain Modifications in Divorce Legislation.

As far as I can determine, no capitalist state at the time provided such benefits to mothers.

Skopic uses this quotation for an anti-Stalin rant:

This, to put it mildly, does not sound like the actions of any socialist state worthy of the name. Instead, it sounds like something Ted Cruz or Ron DeSantis would do if you gave them unlimited power.

When it comes to Stalin and the Soviet Union Skopic is incapable of being objective. His absurd statements here and elsewhere show that he is prejudiced against Stalin to the point where his judgment is disordered. The anti-abortion movement in the US – “Cruz and DeSantis” -- shows no interest in providing the benefits to mothers that the Soviet state was providing in the 1930s.

We must evaluate the Soviet – Stalin’s – policy on abortion on demand not according to the views of progressive people today but in the context of its time and in total, including the benefits to mothers. Viewed historically, Soviet policy was indeed progressive.

Skopic:

This further illustrates the fallacy of taking things out of historical context. Even Skopic concedes that well-known Soviet feminist Alexandra Kollontai, a progressive in her day, supported this policy in the 1940s.

Art

Skopic doesn’t know or, evidently, care anything about Soviet arti.

But these currents existed in an uneasy tension with “socialist realism,” the brainchild of Anatoly Lunacharsky—a Bolshevik commissar who believed that art should be used for didactic purposes, to depict “ideal” workers and communities and instruct people in how they ought to be living their lives.

Skopic gives no evidence for this statement. I cannot find any either. But here is what scholar of Soviet art K. Andrea Rusnock says about Lunacharsky:

Verbally. Lunacharsky was proclaiming [in 1922] that realist art was the appropriate vehicle for conveying the events of the Bolshevik revolution, its achievements, and the heroes and heroines, of the new Soviet state. Despite his words, however, and the party's increasing pressure, Lunacharsky did continue to support avant-garde art until his 1928 resignation as Commissariat of Enlightenment.

Skopic does not cite any source for his misunderstanding of socialist realism. Indeed, there is no single authoritative definition. Here is what Maksim Gorky wrote about it in 1934:

Социалистический реализм утверждает бытие как деяние, как творчество, цель которого — непрерывное развитие ценнейших индивидуальных способностей человека ради победы его над силами природы, ради его здоровья и долголетия, ради великого счастья жить на земле, которую он, сообразно непрерывному росту его потребностей, хочет обрабатывать всю, как прекрасное жилище человечества, объединённого в одну семью.

Socialist realism affirms being as an act, as creativity, the purpose of which is the continuous development of the most valuable individual abilities of mankind for the sake of his victory over the forces of nature, for the sake of his health and longevity, for the sake of the great happiness of living on the earth, all of which he, in accordance with the continuous growth of his needs, wants to cultivate everything, like a beautiful dwelling of mankind, united in one family

Elsewhere in his essay, but not in this context, Skopic quotes Sheila Fitzpatrick, a mainstream anticommunist historian of the Soviet Union. Here is what Fitzpatrick writes about socialist realism:

The formula of “socialist realism’? which the [Soviet Writers’] Union adopted was not originally conceived as a “party line,” any more than the Union was conceived as an instrument of total control over literature. Both were initially intended to cancel out the old RAPP line of proletarian and Communist exclusiveness and make room for literary diversity …

According to literary historian Lawrence Schwartz,

There is direct evidence to support the contention of liberalization. It is true that a plan for literature was devised, but also that it was not devised by Stalin as a devious ploy for dictatorial control over literature. The guidelines on literature were established not as a separate category but as part of a general Party effort to create a working relationship with fellow travelers.

Skopic:

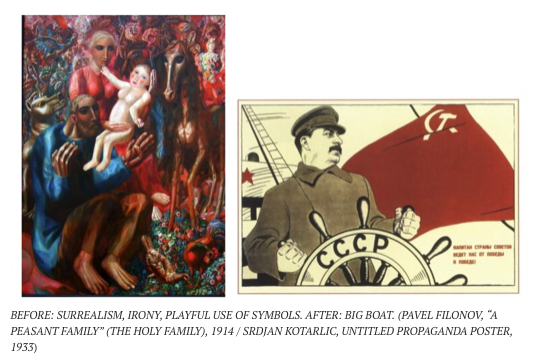

When Stalin took power, he favored this more authoritarian take on art and put strict new restrictions on both the styles that could be used and the content that could be depicted. Non-representational art came to be viewed as “decadent” (just as it was “degenerate” to the Nazis), and it was usually forbidden to display it.

Instead, public space became an endless gallery of kitsch, with propaganda posters showing muscular Soviet workmen hammering rocks, driving tractors, and gazing sternly into the distance. Predictably, many of the posters were tacky heroic portraits of Stalin himself: Stalin marching with happy workers, Stalin holding a baby, Stalin steering a big boat marked “CCCP.”

Skopic does not like socialist realism and representational art. But who cares what Skopic believes? “Kitsch” is simply a term of insult, a way of avoiding historical accuracy.

Skopic confuses fine art with poster art. The Soviets reproduced paintings on postcards for mass distribution and in larger formats for local exhibitions. Exhibitions of original art works took place mainly in cities.

Art for Whom?

Moreover, Skopic fails to understand a basic question: What kind of art should be encouraged? What kind of art can best serve not the individual vision of the artist, but the working class? Skopic values the individual vision. Socialist realism promoted art that was intelligible to and reflected the interest of the collective.

Skopic:

This is not true. According to the biography of Filonov by Anna Laks:

Филонов все 1930-е бедствует, недоедает, одалживает у жены и сестры деньги, судорожно ищет заказы ... Но позиций не сдает, своих работ не продает, потому что знает, заказ — это заработок, а его личное, свободное творчество вместе со школой — это святое, это его миссия, это его пространство, это его храм, где не место ни иноверцам, ни торговцам.

Throughout the 1930s Filonov lived in poverty, malnourished, borrowing money from his wife and sister, frantically looking for orders … But he doesn’t give up his positions, he doesn’t sell his works, because he knows that an order means wages, and his personal, free creativity, together with his school, is sacred, this is his mission, this is his space, this is his temple, where there is no place for non-believers or merchants.

Ему часто хотят заплатить деньги, приручить, „законтрактовать”, купить его работы из мастерской. Он отказывается от очень многих заманчивых предложений, если в их „идеологии” чувствует что-то не свое, „нефилоновское” … (75)

People often want to pay him money, to tame him, to give him a “contract”, to buy his works from the workshop. He refuses very many tempting offers if in their “ideology” he feels something not his own, “non-Filonovian” …

The Soviet state – “Stalin” – did not condemn him to this life. Filonov chose to live in poverty, begging for money from his family, refusing orders for his paintings, refusing to sell his works.

Filonov died during the Siege of Leningrad, where over a million Soviet civilians died.

Skopic:

In some cases, artists who annoyed Stalin were even framed and executed in the same way as his political rivals, as with the poet Titsian Tabidze—a close friend of Boris Pasternak, who barely escaped execution himself.

According to his Russian-language Wikipedia page Titsian Tabidze enjoyed a celebration of his poetry in in Moscow and Leningrad at the beginning of 1937. Later that year he was named as a participant in an anti-Soviet conspiracy by several important Georgian nationalists such as Budu Mdivani. Someone has seen his trial transcript, since the witnesses against him are named.

There is no evidence that Boris Pasternak “barely escaped execution.” On the contrary! According to Evgenii Gromov, author of Stalin: Art and Power (2003):

And he [Pasternak] spoke just as sincerely about the revolution in the poems “The Nine Hundred and Fifth Year” and “Lieutenant Schmidt.” Genuine feeling permeated his “Stalinist” poems. People close to Pasternak noted that he had a kind of love for Stalin. And he believed in him … (306)

Gromov goes on to relate the famous story about how Pasternak telephoned Stalin to intercede – successfully, as it turned out -- on behalf of his friend the poet Osip Mandel’shtam.

Skopic:

In yet another area of life, freedom, playfulness, and exploration had been replaced with grim conformity and fear, and these would be the aesthetic markers that defined the USSR in the eyes of the world.

This is just slander. There was nothing “grim,” “conformist” or “fearful” about Soviet art. Exhibitions and reproductions of social realist art drew mass audiences in the Soviet Union and influenced art worldwide including W.P.A. art in the USA.

World War II

Skopic:

Stalinist authors like Furr and Ludo Martens devote many pages to the war years …

This is false. I have never written about the war years. And I am not a “Stalinist,” as I explain at the beginning of this essay. I defend not Stalin, but the truth.

Skopic:

The images of Red Army soldiers throwing open the gates of Auschwitz will live in human history forever, and at Stalingrad alone, more than a million of them gave their lives—more than the U.S. lost in the entire war. But crucially, these are not Stalin’s victories, nor his sacrifices. He, like Churchill and Roosevelt, was sitting safely behind his desk when the real heroism happened.

Stalin himself publicly recognized the fact that the victory over the Axis was due not to himself or other leaders but to the ordinary Soviet people, without whom the leaders are nothing. Here is what Stalin said at the Kremlin reception in honor of the participants in the victory:

I am not going to say anything extraordinary. I have the simplest, most ordinary toast. I would like to drink to the health of the people who have little rank and no distinguished title. To the people who are considered the “cogs” of the great state mechanism, but without whom all of us marshals and commanders of fronts and armies, to put it bluntly, are not worth a damn thing. Some little “screw” goes wrong - and it's all over. I raise a toast to the simple, ordinary, modest people, to the “cogs” that keep our great state mechanism in active condition in all branches of science, economy and military affairs. There are a great many of them, their name is legion, because they are tens of millions of people. These are humble people. No one writes about them, they have no title, are of low rank, but these are the people who hold us like the foundation holds the structure. I drink to the health of these people, our respected comrades.

Skopic continues:

Apart from this, there’s evidence that Stalin and his paranoia actively harmed the Soviet war effort. Because Trotsky had been the original architect of the Red Army, Stalin always viewed its officer corps with deep suspicion and carried out extensive purges in the years 1937-8 just as he had within the Bolshevik Party itself. “Three of the five marshals, thirteen of the fifteen army commanders, and eight of the nine fleet admirals” were executed, according to one account, together with more than 40,000 men who were dismissed from their posts for various small infractions and accusations of disloyalty.

See below about the high-ranking officers who were, in fact, guilty as charged of conspiring with the German General Staff and Leon Trotsky, who also conspired with Germany and Japan..