Indispensable Books: The Enemy of Nature

By Joel Kovel

Polar bears are the poster creatures for what humans do to the environment.

The obsession with chaotic growth and short-term profits combined with the complete corruption of the political system have finally rendered the environment defenseless against the worst excesses of the plundering corporate class. Meanwhile, the environmental movement —and the public at large—largely co-opted and in disarray, as witnessed the poverty of proper reaction in the case of the BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, seem overwhelmed by the enormousness of the assault. This volume by Joel Kovel is a welcome antidote to the advancing disease. —P. Greanville, May 10, 2010 (date of first publication).

SPECIAL BONUS FOR ACTIVISTS:

Download the whole book free—click here

Download the whole book free—click here

A READ & PONDER SELECTION

By Joel Kovel

Preface to the second edition

For everything that lives is Holy—William Blake

All that is holy is profaned—Karl Marx

1

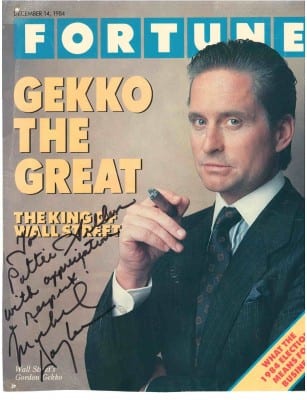

PHOTO: "Drill, Baby, Drill" is the chant of criminally ignorant reactionaries like Sarah Palin, the pinup doll of incipient fascism. Unfortunately, far too many Americans follow such siren calls.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] wrote The Enemy of Nature according to the principle that the truth – a sufficiently generous and expansive truth, it may be added – can make us free. If truth gives clarity and definition to our world, if it weans us from dependency on alienating forces that sap our will and delude our mind, and if it can bring us together with others in a common empowering project – a project that gives us hope that we can become the makers of our own history – why, then, then it makes us free even if what it reveals is terrible to behold. Better this than the unrevealed terror in the dark, unenvisioned, without opening to hope, better than what inertly weighs on us under the aegis of the capitalist order.

.

The Enemy of Nature was written in service of such an ideal. It tries to give expression to an emerging and still incomplete realization that our all-conquering capitalist system of production, the greatest and proudest of all the modalities of transforming nature which the human species has yet devised, the defining influence in modern culture and the organizer of the modern state, is at heart the enemy of nature and therefore humanity’s executioner as well.

.

If our institutions could grasp such an idea, then there would not have been an ecological crisis in the first place and this book would not have to be written. It follows that The Enemy of Nature was born in struggle and for struggle, and that it is for the long haul, as long as it takes. Thus, this second edition. The first, although ignored from above, has had a good, vigorous life from below, a kind of samizdat existence comprised of word-of-mouth networks, little pockets of the alienated and disaffected where the book has taken hold, circuits of distribution on the internet, study groups, a course here and there, a few foreign editions. A second edition is needed, however, to bring the argument up to date.

.

While I have no intention of rewriting the central ideas of a text which, in essence, appears more firmly grounded than ever, keeping faithful to the basic logic demands continual modification. This will be seen chiefly at the beginning and end, the former to bring the reader up to date as to the development of the crisis, and the latter to bear witness to the maturation of the notion of ecosocialism. In between, the critique of capital, the philosophy of nature, the rendering of Marxism in ecological form, the notion of the gendered bifurcation of nature, and those other features that comprise the work’s inner structure will remain largely as before, with a few improvements/updates added here and there. I intend to turn shortly to these themes in an extended study that has been germinating for some time.

.

this score, but the events of the five years since the first edition was published have done nothing to disabuse me of the notion.

.

2 The findings are a puerile mish-mash of local clean-up efforts, greenwashings of one kind or another, the hucksterings of green capitalists, various techno-fixes, and the noises made by governmental agencies.

.

s is virtually all bad, and recounts the steady, albeit fitful and non-linear, disintegration of the planetary ecology.

.

Watch China slide toward ruin and pull the world along with it; watch the coral reefs decay, the polar bears drown, the Indian farmers kill themselves by drinking pesticides, the honeybees fail to come back to their hives, our bodily fluids fill up with unholy effluents as the cancers break out all over despite medical miracles without end, the Niger River delta burn as it destroys the lungs of little children . . . and of course do not miss the inexorability of global warming.

.

The past year has seen an accelerating awareness, a growing anger and realization of the bankruptcy of capital to contend with the crisis it has spawned. How can it, when to overcome the crisis would mean its own liquidation? There is now a widespread assumption, which was much more limited five years ago, that the problem is not this corporation or that, or “industrialization,” technology, or just plain bad luck, but all-devouring capital. This is a salubrious truth, a truth that sharpens the mind and can be worked with and built upon.

.

--

KEITH OLBERMANN [who since those days has became himself a hysterical idiot of the woke liberals stricken with Trump Derangement] deservedly called Sarah Palin an "idiot" on his show. Palin is a moron alright, but a malignant moron, as she admirably serves to fan the flames of human chauvinism to the detriment of the environment, not to mention a long list of rightwing positions.

•••••

.

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION

Growing numbers of people are beginning to realize that capitalism is the uncontrollable force driving our ecological crisis, only to become frozen in their tracks by the awesome implications of the insight. Considering that the very possibility of a future revolves about this notion, I decided to take it up in a comprehensive way, to see whether it is true, and if so, how it came about, and most importantly, what we can do about it.

.

Here is something of how this project began. Summers in the Catskill Mountains of New York State, where I live, are usually quite pleasant. But in 1988, a fierce drought blasted the region from mid-June until well into August. As the weeks went by and the vegetation baked and the wells went dry, I began to ponder something I had recently read, to the effect that rising concentrations of gases emitted by industrial activity would trap solar radiation in the atmosphere and lead to ever-growing climatic destabilization. Though the idea had seemed remote at first, the ruin of my garden brought it alarmingly close to home. Was the drought a fluke of the weather, or, as I was coming to think, was it a tolling bell, calling us to task for a civilization gone wrong? The seared vegetation now appeared a harbinger of something quite dreadful, and a call to act. And so I set out on the path that led to this book. Thirteen years later, after much writing, teaching and organizing, after working with the Greens and running for the US Senate in 1998 and seeking their Presidential nomination in 2000, and after several drafts and false starts, The Enemy of Nature is ready to be placed before the public.

.

It would have been understandable to shrug off the drought as just another piece of odd weather (and indeed nothing that severe has recurred since). But I had for some time become disposed to take a worst-case attitude with respect to anything having to do with the powers-that-be; and since industrial activity was close to the heart of the system, so were its effects on climate drawn into the zone of my suspicion. US imperialism had got me going in this, initially in the context of Vietnam and later in Central America, where an agonizing struggle to defend the Nicaraguan revolution against Uncle Sam was coming to a bad end as the drought struck. The defeat had been bitter and undoubtedly contributed to my irritability, but it provided important lessons as well, chiefly as to the implacability displayed by the system once one looked below its claims of democracy and respect for human rights.

.

Here, far from the pieties, one encounters the effects of capital’s ruthless pressure to expand. Imperialism was such a pattern, manifest politically and across nations. But this selfsame ever-expanding capital was also the superintendent and regulator of the industrial system whose exhalations were trapping solar energy. What had proven true about capital in relation to empire could be applied, therefore, to the realm of nature as well, bringing the human victims and the destabilizations of ecology under the same sign. Climate change was, in effect, another kind of imperialism. Nor was it the only noxious ecological effect of capital’s relentless growth. There was also the sowing of the biosphere with organochlorines and other toxins subtle as well as crude, the wasting of the soil as a result of the “green revolution,” the prodigious species losses, the disintegration of Amazonia, and much more still – the spiralling, interpenetrating tentacles of a great crisis in the relationship between humanity and nature.

.

From this standpoint there appears a greater “ecological crisis,” of which the particular insults to ecosystems are elements. This has further implications. For human beings are part of nature, however ill-at-ease we may be with the role. There is therefore a human ecology as well as an ecology of forests and lakes. It follows that the larger ecological crisis would be generated by, and extend deeply into, an ecologically pathological society. Regarding the matter from this angle provided a more generous view. No longer trapped in a narrow economic determinism, one could see capital as much more than a simple material arrangement, but as something cancerous lodged in the human spirit, produced by, and producer of, the capitalist economy. It takes shape as a queer beast altogether, more a whole way of being than anything else.

.

And if it is a whole way of being that needs changing, then the essential question of “what is to be done?” takes on new dimensions, and ecological politics is about much more than managing the external environment. It has to be thought of, rather, in frankly revolutionary terms. But since the revolution is against the capital that is nature’s enemy, the struggle for an ecologically just and rational society is the logical successor to the socialist movements that agitated the last century and a half before sputtering to an ignominious end. Could we be facing a “next-epoch” socialism – and could the fatal flaws of the first-epoch version be overcome if socialism became ecological?

.

There is a big problem with these ideas, namely, that very few people take them seriously. I have been acutely aware from the beginning of this project that the above conclusions place me at a great distance from so-called mainstream opinion. How could it be otherwise in a time of capitalist triumph, when by definition reasonable folk are led to think that just a bit of tinkering with “market mechanisms” will see us through our ecological difficulties? And as for socialism, why should anyone with an up-to-date mind bother thinking about such a quaint issue, much less trying to overcome its false starts? These difficulties extend over to the fragmented and divided left side of opinion, whether this be the “red” left that inherits the old socialist passion for the working class, or the “green” left that stands for an emerging awareness of the ecological crisis.

.

Socialism, though quite ready to entertain the idea that capital is nature’s enemy, is less sure about being nature’s friend. Most socialists, though they stand for a cleaner environment, decline to take the ecological dimension seriously. They tend to support an strategy where the workers’ state will clean up pollution, but are unwilling to follow the radical changes that an ecological point of view implies as to the character of human needs, the fate of industry, and the question of nature’s intrinsic value. Meanwhile Greens, however dedicated they may be to rethinking the latter questions, resist placing capital at the center of the problem. Green politics tend to be populist or anarchist rather than socialist, hence Greens are quite content to envision an ecologically sane future in which a suitably regulated capitalism, brought down to size and mixed with other forms, continues to regulate social production. Such was essentially the stance of Ralph Nader, whom I challenged in the 2000 presidential primary, with neither intention nor hope of winning, but only to keep the message alive that the root of the problem lies in capital itself.

.

We live at a time when those who think in terms of alternatives to the dominant order court exclusion from polite intellectual society. During my youth, and for generations before, a consensus existed that capitalism was embattled and that its survival was an open question. For the last twenty years or so, however, with the rise of neoliberalism and the collapse of the Soviets, the system has acquired an aura of inevitability and even immortality. It has been quite remarkable to see how readily the intellectual classes have gone along, sheeplike, with these absurd conclusions, disregarding the well-established lessons that nothing lasts forever, that all empires fall, and that a twenty-year ascendancy is scarcely a blink in the flux of time.

.

But the same mentality that went into the recently deceased dot-com mania applies to those who see capitalism as a gift from the gods, destined for immortality. One would think that a moment of doubt would be introduced into the official scenario by the screamingly obvious fact that a society predicated on endless expansion must inevitably collapse its natural base. However, thanks to a superbly effective propaganda apparatus and the intellectual defects wrought by power, such has not so far been the case.

.

Change, if it comes, will have to come from outside the ruling consensus. And there is hopeful evidence that just such an awakening may be taking place. Cracks have been appearing in the globalized edifice, through which a new era of protest is emerging. When the World Trade Organization is forced to hold its meeting in Qatar in order to avoid distruption, or fence itself in inside the walled city of Quebec, or when the President-select, George W. Bush, is forced by protestors at his inauguration to slink fugitive-like along Pennsylvania Avenue in a sealed limousine, then it may fairly be said that a new spirit is in the air, and that the generation now maturing, thrown through no fault of their own into a world defined by the ecological crisis, are also beginning to rise up and take history into their own hands. The Enemy of Nature is written for them, and for all those who recognize the need to break with the given in order to win a future.

.

An attitude of rejection conditioned me to see the 1988 drought as a harbinger of an ecologically ruined society. But that was not the only attitude I brought to the task. I was also working at the time on my History and Spirit, having been stirred by the faith of the Sandinistas, and especially their radical priests, to realize that a refusal is worthless unless coupled with affirmation, and that it takes a notion of the whole of things to gather courage to reach beyond the given.

.

There is a wonderful saying from 1968, which should guide us in the troubled time ahead: to be realistic, one demands the impossible. So let us rise up and do so. Many people helped me on the long journey to this book, too many, I fear, to all be included here, especially if one takes into account, as we should, the many hundreds I met during the political campaigns that provide much of its background. But there is no difficulty in identifying its chief intellectual influence. Soon after I decided to confront the ecological crisis, I decided also to link up with James O’Connor, founder of the journal, Capitalism Nature Socialism, and originator of the school of ecological Marxism that made the most sense to me. It proved one of the most felicitous moments of my career and led to a collaboration which is still active.

.

As my mentor in matters political-economic and toughest critic, but mostly as a dear friend, Jim’s presence is everywhere in this volume (though the truism must be underscored, that its errors are mine alone). I have been indebted throughout to the CNS community for giving me an intellectual home and forum, and for countless instances of comradely help. This begins with Barbara Laurence, and includes the New York editorial group – Paul Bartlett, Paul Cooney, Maarten DeKadt, Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro, Costas Panayotakis, Patty Parmalee, José Tapia and Edward Yuen – along with Daniel Faber and Victor Wallis, of the Boston group, and Alan Rudy.

.

A number of people have taken the trouble to give portions of the manuscript a close reading during various stages in its gestation – Susan Davis, Andy Fisher, DeeDee Halleck, Jonathan Kahn, Cambiz Khosravi, Andrew Nash, Walt Sheasby, and Michelle Syverson – and to them all I am grateful. I am further grateful to Michelle Syverson for the active support she has given this project during its later stages. Among those who have helped in one way or another at different points of the work, I thank Roy Morrison, John Clark, Doug Henwood, Harriet Fraad, Ariel Salleh, Brian Drolet, Leo Panitch, Bertell Ollman, Fiona Salmon, Finley Schaef, Don Boring, Starlene Rankin, Ed Herman, Joan Martinez-Alier, and Nadja Milner- Larson. Mildred Marmur provided, as ever, a guide to that real world which is often too much for me. And to Robert Molteno and the people at Zed, thanks for the help and the opportunity to join the honorable list of works they have shepherded into existence. Last and as ever, not least, except in the ages of its younger members, I thank the family that sustains me. This begins with my DeeDee, and extends to those grandchildren who represent the children of the future for whom the battle must be fought: Rowan, Liam, Tolan, Owen, and Josephine.

•

1 | Introduction

In 1970, growing fears for the integrity of the planet gave rise to a new awareness and a new politics. On April 22, the first “Earth Day” was announced, since to become an annual event of re-dedication to the preservation and enhancement of the environment. The movement affected ordinary people and, remarkably, certain members of the elites, who, organized into a group called the Club of Rome, even dared to announce a theme never before entertained by persons of power. This appeared as the title of their 1972 manifesto, The Limits to Growth:

.

1 Thirty years later, Earth Day 2000 featured a colloquy between Leonardo de Caprio and President Bill Clinton, with much fine talk about saving nature. The anniversary also provided a convenient vantage point for surveying the results of three decades of “limiting growth.” At the dawn of a new millennium, one could observe the following:

.

• The human population had increased from 3.7 billion to 6

billion (62 percent).

• Oil consumption had increased from 46 million barrels a day

to 73 million.

• Natural gas extraction had increased from 34 trillion cubic

feet per year to 95 trillion.

• Coal extraction had gone from 2.2 billion metric tonnes to 3.8

billion.

• The global motor vehicle population had almost tripled, from

246 million to 730 million.

• Air traffic had increased by a factor of six.

• The rate at which trees are consumed to make paper had

doubled, to 200 million metric tons per year.

• Human carbon emissions had increased from 3.9 million

metric tons annually to an estimated 6.4 million – this

despite the additional impetus to cut back caused by an

awareness of global warming, which was not perceived to be a

factor in 1970.

• As for this warming, average temperature increased by 1°f – a

disarmingly small number that, being unevenly distributed,

translates into chaotic weather events (seven of the ten most

destructive storms in recorded history having occurred in the

last decade), and an unpredictable and uncontrollable cascade

of ecological trauma – including now the melting of the

North Pole during the summer of 2000, for the first time in 50

million years, and signs of the disappearance of the “snows of

Kilimanjaro” the year following; since then this melting has

become a fixture.

• Species were vanishing at a rate that has not occurred in 65

million years.

• Fish were being taken at twice the rate as in 1970.

• Forty percent of agricultural soils had been degraded.

• Half of the forests had disappeared.

• Half of the wetlands had been filled or drained.

• One-half of US coastal waters were unfit for fishing or swimming.

• Despite concerted effort to bring to bay the emissions of

ozone-depleting substances, the Antarctic ozone hole was

the largest ever in 2000, some three times the size of the

continental United States; meanwhile, 2,000 tons of such

substances as cause it continue to be emitted every day. 2

• 7.3 billion tons of pollutants were released in the United

States during 1999.3

We can add some other, more immediately human costs:

• Third World debt increased by a factor of eight between 1970

and 2000.

• The gap between rich and poor nations, according to the

United Nations, went from a factor of 3:1 in 1820, to 35:1 in

1950; 44:1 in 1973 – at the beginning of the environmentally

sensitive era – to 72:1 in 1990, roughly two-thirds of the way

through it.

• By 2000 1.2 million women under the age of eighteen were

entering the global sex trade each year.

• 100 million children were homeless and slept on the streets.

.

These figures were mostly gathered around the year 2000, and served to frame the first edition of The Enemy of Nature by calling attention to a remarkable yet greatly underappreciated fact: that the era of environmental awareness, beginning roughly in 1970, has also been the era of greatest environmental breakdown. No sooner, then, did the awareness of a profound threat to humanity’s relationship to nature surface than it became overwhelmed by a greater force outside this awareness.

.

Each of the above observations has had its specific causes – the production of a certain gas, the dynamics of the auto market or of the habitat of a threatened species, etc. – but there must also be a larger issue to account for the rapid acceleration of the set of all such perturbations – and, necessarily tied to this, the appearance of increasingly chaotic interactions between the members of this set. There is, therefore, some greater force at work, setting the numberless manifestations of the crisis into motion and whirling them about like broken twigs in the winds of a hurricane.

.

It is this larger force that the present work investigates, under an obligation imposed by the colossal failure of the reigning environmental awareness. I say “obligation,” because of the gravity of the present crisis. If we take this crisis seriously enough – and what, in the whole history of the human race, has had more momentous and dire implications? – then we are obliged to radically rethink our entire approach. Happily, many more people, including experts of one kind or another, are now recognizing the scope of the crisis and what is at stake. Unhappily, they mostly remain blind to the essential dynamics; thus, the great range of recommendations are puerile rehashes of what has already failed: exhortations to live more frugally, to recognize and respect our embeddedness in nature, to recycle, to find and approve better technologies, to vote into power environmentally responsible politicians, and so forth. None of these recommendations is without merit; they all need to find their place in a comprehensive approach. But what makes that approach comprehensive needs to begin with recognition of the “greater force” whose impulse drives the crisis onward.

.

Now the reader already knows the name of this force from The Enemy of Nature’s subtitle: that we face a choice between “the end of capitalism” or “the end of the world.” So there seems to be no suspense: as a mystery story, The Enemy breaks the basic rule by giving away the killer’s name on the dustjacket. But the crime remains unspecified and the revelation superficial, chosen, I must confess, to catch the reader’s attention and tug at that rising yet indefinite awareness that, yes, this damned capitalist system is wrecking nature. The real work lies ahead – to make that awareness definite, to clarify what capital is and what nature is, to understand capital’s enmity to nature, to understand it as not just an economic system but in relation to the entire human project, to see its antecedents and consequences, and, most importantly, to fathom what can be done about it.

.

There is certainly no time to waste. The five years since The Enemy of Nature appeared have done nothing to dispell its basic indictment. Thus, the World Wildlife Fund’s annual “Living Planet” report on the health of the environment for 2006 indicates that the “ecological footprint,” a complexly-derived term that signifies the degree to which human society consumes and degrades nature, has risen some 20 percent since 2001, the year that The Enemy of Nature went to press.4

.

This has to be understood in context of the only other global parameter that tracks along the same path, namely, the accumulation of capital, which is what the euphemism of “growth” signifies. I do not mean that capital exactly parallels the breakdown of our natural firmament. It really cannot, because capital in its essence is not directly part of nature at all. It is rather a kind of idea in the mind of a natural creature (us) which takes the external form of money and causes that creature to seek more of what capital signifies. As we shall show, it is this seeking, through economy and society, that degrades nature. Thus capital, money-in-action, becomes both a kind of intoxicating god, and also what we call below, a “force field” polarizing our relation to nature in such a way that spells disaster. From being the creature of nature we have become capital’s puppet.

.

A hint of this can be glimpsed in a recent report which outlines the ascendancy of capital over the economic process itself. As of 2005, when the calculations were last made, the money-inaction (stocks, bonds, and other financial assets) flitting about the globe comprised the whopping figure of $140 trillion. As a report in the Wall Street Journal put it, this is more than three times the amount of goods and services created that year.5 It is the motion of this money-wealth that spurs economic activity; thus capital flows induce the flow of nature’s transforming. And the more rapid, i.e. reckless, the flow, the more devastating to nature.

.

This of course is not the WSJ’s conclusion, but one we develop below. The article merely notes that by 2005, cross-border flows hit $6 trillion, more than twice the figure for 2002, the year The Enemy of Nature was published. This is the face of globalization, with capital racing across the planet and sucking nature and humanity into its maw. Moreover, “[g]lobal financial flows are likely to accelerate in the coming years. ‘The growth in trade in financial assets is proceeding about 50% faster than the growth in trade’ in goods and services, says Kenneth Rogoff, an economist at Harvard.” In other words, there is a whirlwind to be reaped.

.

To account for this and point the way toward its transformation, The Enemy of Nature is divided into three parts. In the first, “The Culprit,” we indict capital as what will be called the “efficient cause” of the ecological crisis. But first, this crisis itself needs to be defined, and that is what the next chapter sets out to do, chiefly by introducing certain ecological notions through which the scale of the crisis can be addressed, and by raising the question of causality. The third chapter, “Capital,” lays out the main terms of the indictment, beginning with a case study of the Bhopal disaster, and proceeding to a discussion of what capital is, and how it afflicts ecosystems intensively, by degrading the conditions of its production, and extensively, through ruthless expansion.

.

The next chapter, “Capitalism,” follows upon this by considering the specific form of society built around and for the production of capital. The modes of capital’s expansion are explored, along with the qualities of its social relations and the character of its ruling class, and, decisively, the question of its adaptability. For if capitalism cannot alter its fundamental ecological course, then the case for radical transformation is established. All of which is, needless to say, a grand challenge.

.

The ecological crisis is intellectually difficult and horrific to contemplate, while its outcome must always remain beyond the realm of positive proof. Furthermore, the line of reasoning pursued here entails extremely difficult and unfamiliar political choices. Even though people may accept it in a cursory way, its awful dimensions make resistance to the practical implications inevitable.

.

The argument developed here would be, for many, akin to learning that a trusted and admired guardian – one, moreover, who retains a great deal of power over life – is in reality a cold-blooded killer who has to be put down if one is to survive. Not an easy conclusion to draw, and not an easy path to take, however essential it may be. But that is my problem, and if I believed in prayer, I would pray that my powers are adequate to the task. In the middle section, “The Domination of Nature,” we leave the direct prosecution of the case to establish its wider ground. This is necessary for a number of reasons, chiefly, to avoid a narrow economistic interpretation.

.

In the first of these chapters, the fifth overall, I set out to ground the argument more deeply in the philosophy of nature and human nature. This is entailed in the shift from a merely environmental approach to one that is genuinely ecological, for which purpose it is necessary to talk in terms of human ecosystems and in the human fittedness for ecosystems, i.e. human nature.

.

If the goal of our effort is to build a free society in harmony with nature, then we need to appreciate how capital violates both nature at large and human nature – and we need to understand as well how we can restore a more integral relationship with nature. These ideas are pursued further in Chapter 6, which takes them up in a historical framework and in relation to other varieties of ecophilosophy.

.

We see here that capital stands at the end of a whole set of estrangements from nature, and integrates them into itself. Far from being a merely economic arrangement, then, capital is the culmination of an ancient lesion between humanity and nature. We will argue that domination according to gender stands at the origin of this and shadows everything that follows with what will be called the gendered bifurcation of nature.

.

This means that we need to regard capital as a whole way of being, and not merely a set of economic institutions. It is, therefore, this way of being that has to be radically transformed if the ecological crisis is to be overcome – even though its transforming must necessarily pass through a bringing down of the “economic capital” and its enforcer, the capitalist state. We conclude the chapter with some philosophical reflections, including a compact statement of the role played by the elusive notion of the “dialectic.”

.

Then, in Part III: “Paths to Ecosocialism,” we turn to the question of “What is to be done?” Now the argument becomes political, and, because we are so far removed these days from transforming society, to a blend of utopian and critical thinking. An important distinction between this and the first edition is that these alternatives are emphasized in the light of what to do about the carbon economy that results in the greenhouse effect, and therefore, provides the most salient dynamic of global warming. This entails critically confronting the important contribution of former Vice-President Al Gore, and his Inconvenient Truth.

.

We begin with a survey of existing ecopolitics in Chapter 8, to see what has been done to mend our relation to nature, and to assay its potential for uprooting capital. One aspect of this critique is entirely conventional, if generally underappreciated. We emphasize that capital stems from the separation of our productive power from the possibilities of their realization. It is, at heart, the imprisonment of labor and the stunting of human capacities – capacities that need full and free development in an ecological society. Therefore, all existing ecopolitics have to be judged by the standard of how they succeed in freeing labor, which is to say, of our transformative power. The chapter ranges widely, from the relatively well-established pathways to those relegated to the margins, and it generally finds the existing strategies wanting.

.

It concludes with a discussion of an insufficiently appreciated danger, that ecological movements may become reactionary or even fascistic. Having surveyed what is, we turn in the last two chapters to what could be. In Chapter 9, “Prefiguration,” the general question of what it takes to break loose from capital is addressed. This requires an excursion into the Marxist notion of “use-value,” as that particular point of the economic system open to ecological transformation; and another excursion into the tangled history of socialism, as the record of those efforts that tried – and essentially failed – to liberate labor in the past century. Finally, the chapter turns to the crucial matter of ecological or, as we will call it, ecocentric, production as such, using for this purpose a synthesis with ecofeminism, a doctrine that connects the liberation of gender to that of nature.

.

We conclude with the observation that the key points of activity are “prefigurative,” in that they contain within themselves the germ of transformation; and “interstitial,” in that they are widely dispersed in capitalist society. In the final chapter, “Ecosocialism,” we attempt a mapping from the present scattered and enfeebled condition of resistance to the transformation of capitalism itself. The term “ecosocialism” refers to a society that is recognizably socialist, in that the producers have been reunited with the means of production in a robust efflorescence of democracy; and also recognizably ecological, in that the “limits to growth” are finally respected, and nature is recognized as having intrinsic value, and thereby allowed to resume its inherently formative path. This imagining of ecosocialism does not represent a kind of god-like aspiration to tightly predict the future, but is an effort to show that we can, and had better begin to think in terms of fundamental alternatives to death-dealing capital. To this effect, a number of pertinent questions are addressed, and the whole effort is rounded off with a brief and speculative reflection.

.

Some last points before taking up the argument. I expect some criticism for not giving sufficent weight to the population question in what follows. At no point, for example, does overpopulation appear among the chief candidates for the mantle of prime or efficient cause of the ecological crisis. This is not because I discount the problem of population, which is most grave, but because I do see it as having a secondary dynamic – not secondary in importance, but in the sense of being determined by other features of the system.6 I remain a deeply committed adversary to the recurrent neo-althusianism which holds that if only the lower classes would stop their wanton breeding, all will be well; and I hold that human beings have ample power to regulate population so long as they, and specifically women, have power over the terms of their social existence. To me, giving people that power is the main point, for which purpose we need a world where there are no more lower classes, and where all people are in control of their lives. If people would voluntarily limit their childbearing to one per family, the global population would decline to about one billion in the next century – needless to say, a very problematic option, yet indicative of the possibilities.

.

The Enemy of Nature need make no apologies for moving within the Marxist tradition, and for adhering to fundamental tenets of socialism. Primary among these, and as we will see, theoretically foundational for this work, is the necessity of emancipating labor, or as Marx put it in both the Communist Manifesto and Volume I of Capital (in the section on the fetishism of commodities), developing a “free association” of producers. But its approach is not that of traditional Marxism.

.

What Marx bequeathed was a method and point of view that require fidelity to the particular forms of a given historical epoch, and the transforming of their own vision as history evolves. Since Marxism emerged a century before the ecological crisis matured, we would expect its received form to be both incomplete and flawed when grappling with a society, such as ours, in advanced ecosystemic decay. Marxism needs, therefore, to become more fully ecological in realizing its potential to speak for nature as well as humanity. In practice, this means replacing capitalist with ecocentrically-socialist production through a restoration of use-values open to nature’s intrinsic value.

.

I expect that many will find the views of The Enemy of Nature too one-sided. It will be said that there is a hatred of capitalism here which leads to the minimization of all its splendid achievements, including the “open society,” and its prodigious recuperative powers. Well, it is true that I hate capitalism and would want others to do so as well. Indeed, I hope that this animus has granted me the will to pursue a difficult truth to a transformative end. In any case, if the views expressed here seem harsh and unbalanced, I can only say that there are no end of opportunities to hear hosannas to the greatness of Lord Capital and obtain, as they say, a more nuanced view. Nor is hatred of capital the same, I hasten to add, as hating capitalists, though there are many of these who should be treated as common criminals, and all should be dispossessed of that instrument which corrupts their soul and destroys the natural ground of civilization.

.

This latter group includes myself, along with millions of others who have been tossed by life into the capitalist pot (in my case, for example, by pension funds in the form of tradeable securities; in all cases by holding a bank account or using a credit card).

.

One of the system’s marvels is how it makes all feel complicit in its machinations – or rather, tries to and usually succeeds. But it needn’t succeed; and one way of preventing it from doing so is to realize that in fighting for an ecologically sane society beyond capital, we are not just struggling to survive, but, more fundamentally, to build a better world and a better life upon it for all creatures.

•••

Joel Kovel (born 27 August 1936) is an American politician, academic, writer, and eco-socialist. A practicing psychiatrist and psychoanalyst until the mid-1980s, he has lectured in psychiatry, anthropology,political science and communication studies. He has published many books on his work in psychiatry, psychoanalysis and political activism. Kovel is a member of the Green Party of the United States (GPUS).

Thank you for visiting our animal defence section. Before leaving, please take a moment to reflect on these mind-numbing institutionalized cruelties.

The wheels of business and human food compulsions—often exacerbated by reactionary creeds— are implacable and totally lacking in compassion. This is a downed cow, badly hurt, but still being dragged to slaughter. Click on this image to fully appreciate this horror repeated millions of times every day around the world. With plentiful non-animal meat substitutes that fool the palate, there is no longer reason for this senseless suffering. And meat consumption is a serious ecoanimal crime. The tyranny of the palate must be broken. Please consider changing your habits and those around you in this regard.

The wheels of business and human food compulsions—often exacerbated by reactionary creeds— are implacable and totally lacking in compassion. This is a downed cow, badly hurt, but still being dragged to slaughter. Click on this image to fully appreciate this horror repeated millions of times every day around the world. With plentiful non-animal meat substitutes that fool the palate, there is no longer reason for this senseless suffering. And meat consumption is a serious ecoanimal crime. The tyranny of the palate must be broken. Please consider changing your habits and those around you in this regard.