The Coup in Chile

Ralph Miliband

The story of Chile, what happened during the Allende period, what followed, and what forces ultimately determined that nation's course, is very relevant these days because, in a sort of perverse historical warp, after a few defeats, the most painful in recent memory in Bolivia, the left is showing signs of re-awakening again in Latin America, with popular explosions in Chile, Ecuador, Bolivia, and even Argentina. But perhaps the sweetest irony is that the US itself may now get a taste of that kind of conflict, as Bernie Sanders, certainly several magnitudes less "socialist" than Dr Allende, but certainly "red" enough for the native Yahoos and liberals to go paranoid, appears to have a chance of miraculously winning the 2020 election. I say miraculous because, let's face it, his chances are simply remote. Remote of getting elected, and remote of being allowed to govern. In that sense, the Allende experience should be of deep interest to Sanders and his supporters, just in case. In a nation where many right-wingers sincerely believe that Obama was a communist, and where the obviously center-rightist Democratic party, supposedly the "left" opposition to Trump, is shamelessly in bed with the Pentagon and the CIA, the corporatist status quo is certain to have many helpers. Take a look, then, at this piece by Ralph Milliband, a British Marxist who understood such processes well. (I find his use of the word "regime" to denote Dr Allende's government a bit unfortunate, but that is a minor peeve in an overall thought-provoking article. Another problematic statement is his suggestion that it was Chile's Christian Democracy (a center right phalangist party) that gave direction to the opposition. In fact, it was the Christian Democrats in tacit alliance with the Partido Nacional, the traditional arch-conservative party, and satellite formations. ).—PG

Ralph Miliband on how the reasonable men of capitalism orchestrated a coup against Salvador Allende in Chile 45 years ago today.

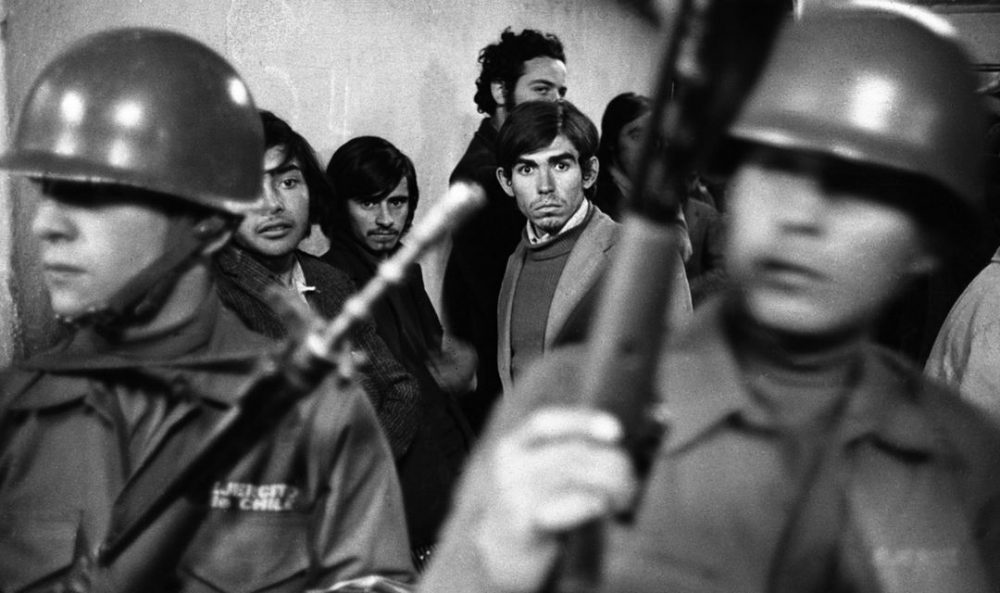

Daniel Cespedes, “a suspected leftist,” at the National Stadium in Santiago. His eyes betray the paralyzing fear inevitable in such horrific circumstances. Many years later the photographer went to Chile to find out what had happened to him. Had he survived? (Credit: David Burnett)

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hat happened in Chile on September 11, 1973 did not suddenly reveal anything new about the ways in which men of power and privilege seek to protect their social order: the history of the last 150 years is spattered with such episodes.

Even so, Chile has at least forced upon many people on the Left some uncomfortable reflections and questions about the “strategy” which is appropriate in Western-type regimes for what is loosely called the “transition to socialism.”

Of course, the Wise Men of the Left, and others too, have hastened to proclaim that Chile is not France, or Italy, or Britain. This is quite true. No country is like any other: circumstances are always different, not only between one country and another, but between one period and another in the same country. Such wisdom makes it possible and plausible to argue that the experience of a country or period cannot provide conclusive “lessons.”

This is also true; and as a matter of general principle, one should be suspicious of people who have instant “lessons” for every occasion. The chances are that they had them well before the occasion arose, and that they are merely trying to fit the experience to their prior views. So let us indeed be cautious about taking or giving “lessons.”

All the same, and however cautiously, there are things to be learnt from experience, or unlearnt, which comes to the same thing. Everybody said, quite rightly, that Chile, alone in Latin America, was a constitutional, parliamentary, liberal, pluralist society, a country which had politics: not exactly like the French, or the American, or the British, but well within the “democratic,” or, as Marxists would call it, the “bourgeois-democratic” fold.

This being the case, and however cautious one wishes to be, what happened in Chile does pose certain questions, requires certain answers, may even provide certain reminders and warnings. It may for instance suggest that stadiums which can be used for purposes other than sport — such as herding left-wing political prisoners — exist not only in Santiago, but in Rome and Paris or for that matter London; or that there must be something wrong with a situation in which Marxism Today, the monthly “Theoretical and Discussion Journal of the (British) Communist Party” has as its major article for its September 1973 issue a speech delivered in July by the General Secretary of the Chilean Communist Party, Luis Corvalan (now in jail awaiting trial, and possible execution), which is entitled “We Say No to Civil War! But Stand Ready to Crush Sedition.”

In the light of what happened, this worthy slogan seems rather pathetic and suggests that there is something badly amiss here, that one must take stock, and try to see things more clearly. Insofar as Chile was a bourgeois democracy, what happened there is about bourgeois democracy, and about what may also happen in other bourgeois democracies.

After all, the Times, on the morrow of the coup, was writing (and the words ought to be carefully memorized by people on the Left): “Whether or not the armed forces were right to do what they have done, the circumstances were such that a reasonable military man could in good faith have thought it his constitutional duty to intervene.”

Should a similar episode occur in Britain, it is a fair bet that, whoever else is inside Wembley Stadium, it won’t be the editor of the Times: he will be busy writing editorials regretting this and that, but agreeing, however reluctantly, that, taking all circumstances into account, and notwithstanding the agonizing character of the choice, there was no alternative but for reasonable military men . . . and so on and so forth.

When Salvador Allende was elected to the presidency of Chile in September 1970, the regime that was then inaugurated was said to constitute a test case for the peaceful or parliamentary transition to socialism. As it turned out over the following three years, this was something of an exaggeration. It achieved a great deal by way of economic and social reform, under incredibly difficult conditions — but it remained a deliberately “moderate” regime: indeed, it does not seem far-fetched to say that the cause of its death, or at least one main cause of it, was its stubborn “moderation.”

But no, we are now told by such experts as Professor Hugh Thomas, from the Graduate School of Contemporary European Studies at Reading University: the trouble was that Allende was much too influenced by such people as Marx and Lenin, “rather than Mill, or Tawney, or Aneurin Bevan, or any other European democratic socialist.” This being the case, Professor Thomas cheerfully goes on, “the Chilean coup d’état cannot by any means be regarded as a defeat for democratic socialism but for Marxist socialism.”

All’s well then, at least for democratic socialism. Mind you, “no doubt Dr Allende had his heart in the right place” (we must be fair about this), but then “there are many reasons for thinking that his prescription was the wrong one for Chile’s maladies, and of course the result of trying to apply it may have led an ‘iron surgeon’ to get to the bedside. The right prescription, of course, was Keynesian socialism, not Marxist.”

That’s it: the trouble with Allende is that he was not Harold Wilson, surrounded by advisers steeped in “Keynesian socialism” as Professor Thomas obviously is.

We must not linger over the Thomases and their ready understanding of why Allende’s policies brought an “iron surgeon” to the bedside of an ailing Chile. But even though the Chilean experience may not have been a test case for the “peaceful transition to socialism,” it still offers a very suggestive example of what may happen when a government does give the impression, in a bourgeois democracy, that it genuinely intends to bring about really serious changes in the social order and to move in socialist directions, in however constitutional and gradual a manner; and whatever else may be said about Allende and his colleagues, and about their strategies and policies, there is no question that this is what they wanted to do.

They were not, and their enemies knew them not to be, mere bourgeois politicians mouthing “socialist” slogans. They were not “Keynesian socialists.” They were serious and dedicated people, as many have shown by dying for what they believed in.

It is this which makes the conservative response to them a matter of great interest and importance, and which makes it necessary for us to try to decode the message, the warning, the “lessons.” For the experience may have crucial significance for other bourgeois democracies: indeed, there is surely no need to insist that some of it is bound to be directly relevant to any “model” of radical social change in this kind of political system.

Struggle and War

Perhaps the most important such message or warning or “lesson” is also the most obvious, and therefore the most easily overlooked. It concerns the notion of class struggle. Assuming one may ignore the view that class struggle is the result of “extremist” propaganda and agitation, there remains the fact that the Left is rather prone to a perspective according to which the class struggle is something waged by the workers and the subordinate classes against the dominant ones.

It is of course that. But class struggle also means, and often means firstof all, the struggle waged by the dominant class, and the state acting on its behalf, against the workers and the subordinate classes. By definition, struggle is not a one way process; but it is just as well to emphasize that it is actively waged by the dominant class or classes, and in many ways much more effectively waged by them than the struggle waged by the subordinate classes.

Secondly, but in the same context, there is a vast difference to be made — sufficiently vast as to require a difference of name — between on the one hand “ordinary” class struggle, of the kind which goes on day in day out in capitalist societies, at economic, political, ideological, micro- and macro-, levels, and which is known to constitute no threat to the capitalist framework within which it occurs; and, on the other hand, class struggle which either does, or which is thought likely to, affect the social order in really fundamental ways.

The first form of class struggle constitutes the stuff, or much of the stuff, of the politics of capitalist society. It is not unimportant, or a mere sham; but neither does it stretch the political system unduly. The latter form of struggle requires to be described not simply as class struggle, but as class war.

Where men of power and privilege (and it is not necessarily those with most power and privilege who are the most uncompromising) do believe that they confront a real threat from below, that the world they know and like and want to preserve seems undermined or in the grip of evil and subversive forces, then an altogether different form of struggle comes into operation, whose acuity, dimensions, and universality warrants the label “class war.”

Chile had known class struggle within a bourgeois democratic framework for many decades: that was its tradition. With the coming to the presidency of Allende, the conservative forces progressively turned class struggle into class war — and here too, it is worth stressing that it was the conservative forces which turned the one into the other.

Before looking at this a little more closely, I want to deal with one issue that has often been raised in connection with the Chilean experience, namely the matter of electoral percentages. It has often been said that Allende, as the presidential candidate of a six-party coalition, only obtained 36 percent of the votes in September 1970, the implication being that if only he had obtained, say, 51 percent of the votes, the attitude of the conservative forces towards him and his administration would have been very different. There is one sense in which this may be true; and another sense in which it seems to me to be dangerous nonsense.

To take the latter point first: one of the most knowledgeable French writers on Latin America, Marcel Niedergang, has published one piece of documentation which is relevant to the issue. This is the testimony of Juan Garces, one of Allende’s personal political advisers over three years who, on the direct orders of the president, escaped from the Moneda Palace after it had come under siege on September 11.

In Garces’s view, it was precisely after the governmental coalition had increased its electoral percentage to 44 percent in the legislative elections of March 1973 that the conservative forces began to think seriously about a coup. “After the elections of March,” Garces said, “a legal coup d’état was no longer possible, since the two-thirds majority required to achieve the constitutional impeachment of the president could not be reached. The Right then understood that the electoral way was exhausted and that the way which remained was that of force.”

This has been confirmed by one of the main promoters of the coup, the Air Force general Gustavo Leigh, who told the correspondent in Chile of the Corriere della Sera that “we began preparations for the overthrow of Allende in March 1973, immediately after the legislative elections.”

Such evidence is not finally conclusive. But it makes good sense. Writing before it was available, Maurice Duverger noted that while Allende was supported by a little more than a third of Chileans at the beginning of his presidency, he had almost half of them supporting him when the coup occurred; and that half was the one that was most hard hit by material difficulties. He writes:

Here is probably the major reason for the military putsch. So long as the Chilean right believed that the experience of Popular Unity would come to an end by the will of the electors, it maintained a democratic attitude. It was worth respecting the Constitution while waiting for the storm to pass. When the Right came to fear that it would not pass and that the play of liberal institutions would result in the maintenance of Salvador Allende in power and in the development of socialism, it preferred violence to the law.

Duverger probably exaggerates the “democratic attitude” of the Right and its respect for the Constitution before the elections of March 1973, but his main point does, as I suggested earlier, seem very reasonable.

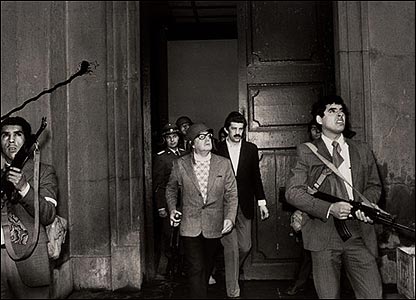

On September 11, 1973, president Salvador Allende appears shortly before his death in the presidential palace La Moneda during Pinochet’s military coup. It is the last known image of the president, rifle in hand, determined to resist till the bitter end.

Its implications are very large: namely, that as far as the conservative forces are concerned, electoral percentages, however high they may be, do not confer legitimacy upon a government which appears to them to be bent on policies they deem to be actually or potentially disastrous.

Nor is this in the least remarkable: for here, in the eyes of the Right, are vicious demagogues, class traitors, fools, gangsters, and crooks, supported by an ignorant rabble, engaged in bringing about ruin and chaos upon an hitherto peaceful and agreeable country, etc. The script is familiar. The idea that, from such a perspective, percentages of support are of any consequence is naive and absurd: what matters, for the Right, is not the percentage of votes by which a left-wing government is supported, but the purposes by which it is moved. If the purposes are wrong, deeply and fundamentally wrong, electoral percentages are an irrelevance.

There is, however, a sense in which percentages do matter in the kind of political situation which confronts the Right in Chilean-type conditions. This is that the higher the percentage of votes cast in any election for the Left, the more likely it is that the conservative forces will be intimidated, demoralized, divided, and uncertain as to their course.

These forces are not homogeneous; and it is obvious that electoral demonstrations of popular support are very useful to the Left, in its confrontation with the Right, so long as the Left does not take them to be decisive. In other words, percentages may help to intimidate the Right — but not to disarm it.

It may well be that the Right would not have dared strike when it did if Allende had obtained higher electoral percentages. But if, having obtained these percentages, Allende had continued to pursue the course on which he was bent, the Right would have struck whenever opportunity had offered. The problem was to deny it the opportunity; or, failing this, to make sure that the confrontation would occur on the most favorable possible terms.

The Opposition

I now propose to return to the question of class struggle and class war and to the conservative forces which wage it, with particular reference to Chile, though the considerations I am offering here do not only apply to Chile, least of all in terms of the nature of the conservative forces which have to be taken into account, and which I shall examine in turn, relating this to the forms of struggle in which these different forces engage:

I. Society as Battlefield

To speak of “the conservative forces,” as I have done so far, is not to imply the existence of a homogeneous economic, social, or political bloc, either in Chile or anywhere else. In Chile, it was among other things the divisions between different elements among these conservative forces which made it possible for Allende to come to the presidency in the first place.

Even so, when these divisions have duly been taken into account, it is worth stressing that a crucial aspect of class struggle is waged by these forces as a whole, in the sense that the struggle occurs all over “civil society,” has no front, no specific focus, no particular strategy, no elaborate leadership or organization: it is the daily battle fought by every member of the disaffected upper and middle classes, each in his own way, and by a large part of the lower middle class as well.

It is fought out of a sentiment which Evelyn Waugh, recalling the horrors of the Attlee regimein Britain after 1945, expressed admirably when he wrote in 1959 that, in those years of Labour government, “the kingdom seemed to be under enemy occupation.” Enemy occupation invites various forms of resistance, and everybody has to do his little bit.

It includes middle-class “housewives” demonstrating by banging pots and pans in front of the Presidential Palace; factory owners sabotaging production; merchants hoarding stocks; newspaper proprietors and their subordinates engaging in ceaseless campaigns against the government; landlords impeding land reform; the spreading of what was, in wartime Britain, called “alarm and despondency” (and incidentally punishable by law): in short, anything that influential, well-off, educated (or not so well-educated) people can do to impede a hated government.

Taken as a “detotalized totality,” the harm that can thus be done is very considerable — and I have not mentioned the upper professionals, the doctors, the lawyers, the state officials, whose capacity to slow down the running of a society, of any society, must be reckoned as being high. Nothing very dramatic is required: just an individual rejection in one’s daily life and activity of the regime’s legitimacy, which turns by itself into a vast collective enterprise in the production of disruption.

It may be assumed that the vast majority of members of the upper and middle classes (not all by any means) will remain irrevocably opposed to the new regime. The question of the lower middle class is rather more complex. The first requirement in this connection is to make a radical distinction between lower professional and white collar workers, technicians, lower managerial staffs, etc., on the one hand, and small capitalists and micro-traders on the other.

The former are an integral part of that “collective worker,” of which Marx spoke more than a hundred years ago; and they are involved, like the industrial working class, in the production of surplus value. This is not to say that this class or stratum will necessarily see itself as part of the working class, or that it will “automatically” support left-wing policies (nor will the working class proper); but it does mean that there is here at least a solid basis for alliance.

This is much more doubtful, in fact most probably untrue, for the other part of the lower middle class, the small entrepreneur and the micro-trader. In the article quoted earlier, Maurice Duverger suggests that “the first condition for the democratic transition to socialism in a Western country of the French type is that a left-wing government should reassure the ‘classes moyennes’ about their fate under the future regime, so as to dissociate them from the kernel of big capitalists who are for their part condemned to disappear or to submit to a strict control.”

The trouble with this is that, in so far as the “classes moyennes” are taken to mean small capitalists and small traders (and Duverger makes it clear that he does mean them), the attempt is doomed from the start. In order to accommodate them, he wants “the evolution towards socialism to be very gradual and very slow, so as to rally at each stage a substantial part of those who feared it at the start.” Moreover, small enterprises must be assured that their fate will be better than under monopoly or oligopolistic capitalism.

It is interesting, and would be amusing if the matter was not very serious, that the realism which Professor Duverger is able to display in regard to Chile deserts him as soon as he comes closer to home. His scenario is ridiculous; and even if it were not, there is no way in which small enterprises can be given the appropriate assurances.

I should not like to give the impression that I am advocating the liquidation of middle and small urban French kulaks: what I am saying is that to adapt the pace of the transition to socialism to the hopes and fears of this class is to advocate paralysis or to prepare for defeat. Better not to start at all. How to deal with the problem is a different matter. But it is important to start with the fact that as a class or social stratum, this element must be reckoned as part of the conservative forces.

This certainly appears to have been the case in Chile, notably with regard to the now-notorious 40,000 lorry owners, whose repeated strikes helped to increase the government’s difficulties. These strikes, excellently coordinated, and quite possibly subsidized from outside sources, highlight the problem which a left-wing government must expect to face, to a greater or lesser degree depending on the country, in a sector of considerable economic importance in terms of distribution.

The problem is further and ironically highlighted by the fact that, according to United Nations statistical sources, it was this “classe moyenne” which had done best under Allende’s regime in regard to the distribution of the national income. Thus, it would appear that the poorest 50 percent of the population saw its share of the total increase from 16.1 percent to 17.6 percent; that of the “middle class” (45 percent of the population) increased from 53.9 percent to 57.7 percent; while the richest 5 percent dropped from 30 percent to 24.7 percent. This is hardly the picture of a middle class squeezed to death — hence the significance of its hostility.

II. External conservative intervention

It is not possible to discuss class war anywhere, least of all in Latin America, without bringing into account external intervention, more specifically and obviously the intervention of United States imperialism, as represented both by private concerns and by the American state itself. The activities of ITT have received considerable publicity, as well as its plans for plunging the country into chaos so as to get “friendly military men” to make a coup.

Nor of course was ITT the only major American firm working in Chile: there was in fact no important sector of the Chilean economy that was not penetrated and in some cases dominated by American enterprises: their hostility to the Allende regime must have greatly increased the latter’s economic, social, and political difficulties. Everybody knows that Chile’s balance of payments very largely depends on its copper exports: but the world price of copper, which had almost been halved in 1970, remained at that low level until the end of 1972; and American pressure was exercised throughout the world to place an embargo on Chilean copper.

In addition, there was strong and successful pressure by the United States on the World Bank to refuse loans and credits to Chile, not that much pressure was needed, either on the World Bank or on other banking institutions. A few days after the coup, the Guardian noted that “the net new advances which were frozen as a result of the US pressure, included sums totaling £30 millions: all for projects which the World Bank had already cleared as worth backing.”

The president of the World Bank is of course Mr Robert McNamara. It was at one time being said that Mr McNamara had undergone some kind of spiritual conversion out of remorse for his part, when US Secretary of State for Defence, in inflicting so much suffering on the Vietnamese people: under his direction, the World Bank was actually going to help the poor countries. What those who were peddling this stuff omitted to add was that there was a condition — that the poor countries should show the utmost regard, as Chile did not, for the claims of private enterprise, notably American private enterprise.

Allende’s regime was, from the start, faced with a relentless American attempt at economic strangulation. In comparison with this fact, which must be taken in conjunction with the economic sabotage in which the internal conservative economic interests engaged, the mistakes which were committed by the regime are of relatively minor importance — even though so much is made of them not only by critics but by friends of the Allende government.

The really remarkable thing, against such odds, is not the mistakes, but that the regime held out economically as long as it did; the more so since it was systematically impeded from taking necessary action by the opposition parties in Parliament.

In this perspective, the question whether the United States government was or was not directly involved in the preparation of the military coup is not particularly important. It certainly had foreknowledge of the coup. The Chilean military had close associations with the United States military. And it would obviously be stupid to think that the kind of people who run the government of the United States would shrink from active involvement in a coup, or in its initiation.

The important point here, however, is that the US government had done its considerable best over the previous three years to lay the ground for the overthrow of the Allende regime by waging economic warfare against it.

III. The conservative political parties.

The kind of class struggle conducted by conservative forces in civil society to which reference was made earlier does ultimately require direction and political articulation, both in Parliament and in the country at large, if it is to be turned into a really effective political force. This direction is provided by conservative parties, and was mainly provided in Chile by Christian Democracy.

Like the Christian Democratic Union in Germany and the Christian Democratic Party in Italy, Christian Democracy in Chile included many different tendencies, from various forms of radicalism (though most radicals went off to form their own groupings after Allende came to power) to extreme conservatism. But it represented in essence the conservative constitutional right, the party of government, one of whose main figures, Eduardo Frei, had been president before Allende.

With steadily growing determination, this conservative constitutional right sought by every means in its power this side of legality to block the government’s actions and to prevent it from functioning properly. Supporters of parliamentarism always say that its operation depends upon the achievement of a certain degree of cooperation between government and opposition; and they are no doubt right. But Allende’s government was denied this cooperation from the very people who never cease to proclaim their dedication to parliamentary democracy and constitutionalism.

Here too, on the legislative front, class struggle easily turned into class war. Legislative assemblies are, with some qualifications that are not relevant here, part of the state system; and in Chile, the legislative assembly was solidly under opposition control. So were other important parts of the state system, to which I shall turn in a moment.

The opposition’s resistance to the government, in Parliament and out, did not assume its full dimensions until the victory which the Popular Unity coalition scored in the elections of March 1973. By the late spring, the erstwhile constitutionalists and parliamentarists were launched on the course towards military intervention.

After the abortive putsch of June 29, which marks the effective beginning of the final crisis, Allende tried to reach a compromise with the leaders of Christian Democracy, Aylwin and Frei. They refused, and increased their pressure on the government. On August 22, the National Assembly which their party dominated actually passed a motion which effectively called on the Army “to put an end to situations which constituted a violation of the Constitution.” In the Chilean case at least, there can be no question of the direct responsibility which these politicians bear for the overthrow of the Allende regime.

No doubt, the Christian Democratic leaders would have preferred it if they could have brought down Allende without resort to force, and within the framework of the Constitution. Bourgeois politicians do not like military coups, not least because such coups deprive them of their role. But like it or not, and however steeped in constitutionalism they may be, most such politicians will turn to the military where they feel circumstances demand it.

The calculations which go into the making of the decision that circumstances do demand resort to illegality are many and complex. These calculations include pressures and promptings of different kinds and weight.

One such pressure is the general, diffuse pressure of the class or classes to which these politicians belong. “Il faut en finir,” they are told from all quarters, or rather from quarters to which they pay heed; and this matters in the drift towards putschism. But another pressure which becomes increasingly important as the crisis grows is that of groups on the right of the constitutional conservatives, who in such circumstances become an element to be reckoned with.

IV. Fascist-type groupings

The Allende regime had to contend with much organized violence from fascist-type groupings. This extreme right-wing guerilla or commando activity grew to fever pitch in the last months before the coup, involved the blowing up of electric pylons, attacks on left-wing militants, and other such actions which contributed greatly to the general sense that the crisis must somehow be brought to an end.

Here again, action of this type, in “normal” circumstances of class conflict, are of no great political significance, certainly not of such significance as to threaten a regime or even to indent it very much. So long as the bulk of the conservative forces remain in the constitutionalist camp, fascist-type groupings remain isolated, even shunned by the traditional right.

But in exceptional circumstances, one speaks to people one would not otherwise be seen dead with in the same room; one gives a nod and a wink where a frown and a rebuke would earlier have been an almost automatic response. “Youngsters will be youngsters,” now indulgently say their conservative elders. “Of course, they are wild and do dreadful things. But then look whom they are doing it to, and what do you expect when you are ruled by demagogues, criminals, and crooks.” So it came about that groups like Fatherland and Freedom operated more and more boldly in Chile, helped to increase the sense of crisis, and encouraged the politicians to think in terms of drastic solutions to it.

V. Administrative and judicial opposition

Conservative forces anywhere can always count on the more or less explicit support or acquiescence or sympathy of the members of the upper echelons of the state system; and for that matter, of many if not most members of the lower echelons as well. By social origin, education, social status, kinship and friendship connections, the upper echelons, to focus on them, are an intrinsic part of the conservative camp; and if none of these factors were operative, ideological dispositions would certainly place them there.

Top civil servants and members of the judiciary may, in ideological terms, range all the way from mild liberalism to extreme conservatism, but mild liberalism, at the progressive end, is where the spectrum has to stop. In “normal” conditions of class conflict, this may not find much expression except in terms of the kind of implicit or explicit bias which such people must be expected to have.

In crisis conditions, on the other hand, in times when class struggle assumes the character of class war, these members of the state personnel become active participants in the battle and are most likely to want to do their bit in the patriotic effort to save their beloved country, not to speak of their beloved positions, from the dangers that threaten.

The Allende regime inherited a state personnel which had long been involved in the rule of the conservative parties and which cannot have included many people who viewed the new regime with any kind of sympathy, to put it no higher. Much in this respect was changed with Allende’s election, insofar as new personnel, which supported the Popular Unity coalition, came to occupy top positions in the state system.

Even so, and in the prevailing circumstances perhaps inevitably, the middle and lower ranks of that system continued to be staffed by established and traditional bureaucrats. The power of such people can be very great. The writ may be issued from on high: but they are in a good position to see to it that it does not run, or that it does not run as it should.

To vary the metaphor, the machine does not respond properly because the mechanics in actual charge of it have no particular desire that it should respond properly. The greater the sense of crisis, the less willing the mechanics are likely to be; and the less willing they are, the greater the crisis.

Yet, despite everything, the Allende regime did not “collapse.” Despite the legislative obstruction, administrative sabotage, political warfare, foreign intervention, economic shortages, internal divisions, etc. — despite all this, the regime held. That, for the politicians and the classes they represented, was the trouble.

In an article which I shall presently want to criticize, Eric Hobsbawm notes quite rightly that “to those commentators on the Right, who ask what other choice remained open to Allende’s opponents but a coup, the simple answer is: not to make a coup.” This, however, meant incurring the risk that Allende might yet pull out of the difficulties he faced.

Indeed, it would appear that, on the day before the coup, he and his ministers had decided on a last constitutional throw, namely a plebiscite, which was to be announced on September 11. He hoped that, if he won it, he might give pause to the putschists, and give himself new room for action. Had he lost, he would have resigned, in the hope that the forces of the Left would one day be in a better position to exercise power.

Whatever may be thought of this strategy, of which the conservative politicians must have had knowledge, it risked prolonging the crisis which they were frantic to bring to an end; and this meant acceptance of, indeed active support for, the coup which the military men had been preparing. In the end, and in the face of the danger presented by popular support for Allende, there was nothing for it: the murderers had to be called in.

VI. The military

Chilean dictator and Washington henchman Gen. Augusto Pinochet: his treacherous ilk is always on tap in America's long tortured backyard.

We had of course been told again and again that the military in Chile, unlike the military in every other Latin American country, was non-political, politically neutral, constitutionally-minded, etc.; and though the point was somewhat overdone, it was broadly speaking true that the military in Chile did not “mix in politics.” Nor is there any reason to doubt that, at the time when Allende came to power and for some time after, the military did not wish to intervene and mount a coup.

It was after “chaos” had been created, and extreme political instability brought about, and the weakness of the regime’s response in face of crisis had been revealed (of which more later) that the conservative dispositions of the military came to the fore, and then decisively tilted the balance. For it would be nonsense to think that “neutrality” and “non-political attitudes” on the part of the armed forces meant that they did not have definite ideological dispositions, and that these dispositions were not definitely conservative.

As Marcel Niedergang also notes, “whatever may have been said, there never were high ranking officers who were socialists, let alone communists. There were two camps: the partisans of legality and the enemies of the left-wing government. The second, more and morenumerous, finally won out.”

The italics in this quotation are intended to convey the crucial dynamic which occurred in Chile and which affected the military as well as all other protagonists. This notion of dynamic process is essential to the analysis of any such kind of situation: people who are thus and thus at one time, and who are or are not willing to do this or that, change under the impact of rapidly moving events. Of course, they mostly change within a certain range of choices: but in such situations, the shift may nevertheless be very great.

Thus conservative but constitutionally-minded army men, in certain situations, become just this much more conservative-minded: and this means that they cease to be constitutionally-minded. The obvious question is what it is that brings about the shift. In part, no doubt, it lies in the worsening “objective” situation; in part also, in the pressure generated by conservative forces.

But to a very large extent, it lies in the position adopted, and seen to be adopted, by the government of the day. As I understand it, the Allende administration’s weak response to the attempted coup of June 29, its steady retreat before the conservative forces (and the military) in the ensuing weeks, and its loss by resignation of General Prats, the one general who had appeared firmly prepared to stand by the regime — all this must have had a lot to do with the fact that the enemies of the regime in the armed forces (meaning the military men who were prepared to make a coup) grew “more and more numerous.” In these matters, there is one law which holds: the weaker the government, the bolder its enemies, and the more numerous they become day by day.

Thus it was that these “constitutional” generals struck on September 11, and put into effect what had — significantly in the light of the massacre of left-wingers in Indonesia — been labelled Operation Djakarta. Before we turn to the next part of this story, the part which concerns the actions of the Allende regime, its strategy and conduct, it is as well to stress the savagery of the repression unleashed by the coup, and to underline the responsibility which the conservative politicians bear for it.

Writing in the immediate aftermath of the Paris Commune, and while the Communards were still being killed, Marx bitterly noted that “the civilization and justice of bourgeois order comes out in its lurid light whenever the slaves and drudges of that order rise against their masters. Then this civilization and order stand forth as undisguised savagery and lawless revenge.” The words apply well to Chile after the coup. Thus, that not very left-wing magazine Newsweek had a report from its correspondent in Santiago shortly after the coup, headed “Slaughterhouse in Santiago,” which went as follows:

Last week, I slipped through a side door into the Santiago city morgue, flashing my junta press pass with all the impatient authority of a high official. One hundred and fifty dead bodies were laid out on the ground floor, awaiting identification by family members. Upstairs, I passed through a swing door and there in a dimly lit corridor lay at least fifty more bodies, squeezed one against another, their heads propped up against the wall. They were all naked.

Most had been shot at close range under the chin. Some had been machine-gunned in the body. Their chests had been slit open and sewn together grotesquely in what presumably had been a pro formaautopsy. They were all young and, judging from the roughness of their hands, all from the working class. A couple of them were girls, distinguishable among the massed bodies only by the curves of their breasts. Most of their heads had been crushed. I remained for perhaps two minutes at most, then left.

Workers at the morgue have been warned that they will be court-martialled and shot if they reveal what is going on there. But the women who go in to look at the bodies say there are between 100 and 150 on the ground floor every day. And I was able to obtain an official morgue body-count from the daughter of a member of its staff: by the fourteenth day following the coup, she said, the morgue had received and processed 2796 corpses.

On the same day as it carried this report, the London Timescommented in an editorial that “the existence of a war or something very like it clearly explains the drastic severity of the new regime which has taken so many observers by surprise.”

The “war” was of course The Times’s own invention. Having invented it, it then went on to observe that “a military government confronted by widespread armed opposition is unlikely to be over-punctilious either about constitutional niceties or even about basic human rights.” Still, lest it be thought that it approved the “drastic severity” of the new regime, the paper told its readers that “it must remain the hope of Chile’s friends abroad, as no doubt of the great majority of Chileans, that human rights will soon be fully respected and that constitutional government will before long be restored.” Amen.

No one knows how many people have been killed in the terror that followed the coup, and how many people will yet die as a result of it. Had a left-wing government shown one tenth of the junta’s ruthlessness, screaming headlines across the whole “civilized” world would have denounced it day in day out.

As it is, the matter was quickly passed over and hardly a pip squeaked when a British government rushed in, eleven days after the coup, to recognize the junta. But then so did most other freedom-loving Western governments.

We may take it that the well-to-do in Chile shared and more than shared the sentiments of the editor of the London Times that, given the circumstances, the military could not be expected to be “over-punctilious.” Here too, Hobsbawm puts it very well when he says that “the Left has generally underestimated the fear and hatred of the Right, the ease with which well-dressed men and women acquire a taste for blood.”

This is an old story. In his Flaubert, Sartre quotes Edmond de Goncourt’s Diary entry for May 31, 1871, immediately after the Paris Commune had been crushed:

It’s good. There has been no conciliation or compromise. The solution has been brutal. It has been pure force . . . a bloodletting such as this, by killing the militant part of the population (‘la partie bataillante de la population’) puts off by a generation the new revolution. It is twenty years of rest which the old society has in front of it if the rulers dare all that needs to be dared at this moment.

Goncourt, as we know, had no need to worry. Nor has the Chilean middle class, if the military not only dare, but are able, i.e. are allowed, to give Chile “twenty years of rest.” A woman journalist with a long experience of Chile reports, three weeks after the coup, the “jubilation” of her upper class friends who had long prayed for it. These ladies would not be likely to be unduly disturbed by the massacre of left-wing militants. Nor would their husbands.

What did apparently disturb the conservative politicians was the thoroughness with which the military went about restoring “law and order.” Hunting down and shooting militants is one thing, as is book-burning and the regimentation of the universities. But dissolving the National Assembly, denouncing “politics” and toying with the idea of a fascist-type “corporatist” state, as some of the generals are doing, is something else, and rather more serious.

Soon after the coup, the leaders of Christian Democracy, who had played such a major role in bringing it about, and who continued to express support for the junta, were nevertheless beginning to express their “disquiet” about some of its inclinations.

Indeed, ex-President Frei went so far, stout fellow, as to confide to a French journalist his belief that “Christian Democracy will have to go into opposition two or three months from now” — presumably after the military had butchered enough left-wing militants. In studying the conduct and declarations of men such as these, one understands better the savage contempt which Marx expressed for the bourgeois politicians he excoriated in his historical writings. The breed has not changed.

The Cost of Conciliation

The configuration of conservative forces which has been presented in the previous section must be expected to exist in any bourgeois democracy, not of course in the same proportions or with exact parallels in any particular country — but the pattern of Chile is not unique. This being the case, it becomes the more important to get as close as one can to an accurate analysis of the response of the Allende regime to the challenge that was posed to it by these forces.

As it happens, and while there is and will continue to be endless controversy on the Left as to who bears the responsibility for what went wrong (if anybody does), and whether there was anything else that could have been done, there can be very little controversy as to what the Allende regime’s strategy actually was. Nor in fact is there, on the Left. Both the Wise Men and the Wild Men of the Left are at least agreed that Allende’s strategy was to effect a constitutional and peaceful transition in the direction of socialism.

The Wise Men of the Left opine that this was the only possible and desirable path to take. The Wild Men of the Left assert that it was the path to disaster. The latter turned out to be right: but whether for the right reasons remains to be seen. In any case, there are various questions which arise here, and which are much too important and much too complex to be resolved by slogans. It is with some of these questions that I should like to deal here.

To begin at the beginning: namely with the manner in which the Left’s coming to power — or to office — must be envisaged in bourgeois democracies. The overwhelming chances are that this will occur via the electoral success of a left coalition of Communists, Socialists and other groupings of more or less radical tendencies. The reason for saying this is not that a crisis might not occur, which would open possibilities of a different kind — it may be for instance that May 1968 in France was a crisis of such a kind.

But whether for good reasons or bad, the parties which might be able to take power in this type of situation, namely the major formations of the Left, including in particular the Communist Parties of France and Italy, have absolutely no intention of embarking on any such course, and do in fact strongly believe that to do so would invite certain disaster and set back the working class movement for generations to come. Their attitude might change if circumstances of a kind that cannot be anticipated arose — for instance the clear imminence or actual beginning of a right-wing coup. But this is speculation.

What is not speculation is that these vast formations, which command the support of the bulk of the organized working class, and which will go on commanding it for a very long time to come, are utterly committed to the achievement of power — or of office — by electoral and constitutional means. This was also the position of the coalition led by Allende in Chile.

There was a time when many people on the Left said that, if a Left clearly committed to massive economic and social changes looked like winning an election, the Right would not “allow” it to do so — i.e. it would launch a pre-emptive strike by way of a coup.

This has ceased to be a fashionable view: it is rightly or wrongly felt that, in “normal” circumstances, the Right would be in no position to decide whether it could or could not “allow” elections to take place. Whatever else it and the government might do to influence the results, they could not actually take the risk of preventing the elections from being held.

The present view on the “extreme” left tends to be that, even if this is so, and admitting that it is likely to be so, any such electoral victory is, by definition, bound to be barren. The argument, or one of the main arguments on which this is based, is that the achievement of an electoral victory can only be bought at the cost of so much maneuver and compromise, so much “electioneering” as to mean very little.

There seems to me to be rather more in this than the Wise Men of the Left are willing to grant; but not necessarily quite as much as their opponents insist must be the case. Few things in these matters are capable of being settled by definition.

Nor have opponents of the “electoral road” much to offer by way of an alternative, in relation to bourgeois democracies in advanced capitalist societies; and such alternatives as they do offer have so far proved entirely unattractive to the bulk of the people on whose support the realization of these alternatives precisely depends; and there is no very good reason to believe that this will change dramatically in any future that must be taken into account.

In other words, it must be assumed that, in countries with this kind of political system, it is by way of electoral victory that the forces of the Left will find themselves in office. The really important question is what happens then. For as Marx also noted at the time of the Paris Commune, electoral victory only gives one the right to rule, not the power to rule.

Unless one takes it for granted that this right to rule cannot, in these circumstances, ever be transmuted into the power to rule, it is at this point that the Left confronts complex questions which it has so far probed only very imperfectly: it is here that slogans, rhetoric and incantation have most readily been used as substitutes for the hard grind of realistic political cogitation. From this point of view, Chile offers some extremely important pointers and “lessons” as to what is, or perhaps what is not, to be done.

The strategy adopted by the forces of the Chilean left had one characteristic not often associated with the coalition, namely a high degree of inflexibility. In saying this, I mean that Allende and his allies had decided upon certain lines of action, and of inaction, well before they came to office. They had decided to proceed with careful regard to constitutionalism, legalism, and gradualism; and also, relatedly, that they would do everything to avoid civil war.

Having decided upon this before they came to office, they stuck to it right through, up to the very end, notwithstanding changing circumstances. Yet, it may well be that what was right and proper and inevitable at the beginning had become suicidal as the struggle developed.

What is at issue here is not “reform versus revolution”: it is that Allende and his colleagues were wedded to a particular version of the “reformist” model, which eventually made it impossible for them to respond to the challenge they faced. This needs some further elaboration.

To achieve office by electoral means involves moving into a house long occupied by people of very different dispositions — indeed it involves moving into a house many rooms of which continue to be occupied by such people.

In other words, Allende’s victory at the polls — such as it was — meant the occupation by the Left of one element of the state system, the presidential-executive one — an extremely important element, perhaps the most important, but not obviously the only one. Having achieved this partial occupation, the president and his administration began the task of carrying out their policies by “working” the system of which they had become a part.

In so doing, they were undoubtedly contravening an essential tenet of the Marxist canon. As Marx wrote in a famous letter to Kugelmann at the time of the Paris Commune, “the next attempt of the French Revolution will be no longer, as before, to transfer the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to another, but to smash it, and this is the preliminary condition for every real people’s revolution on the continent.”

Similarly in “The Civil War in France,” Marx notes that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes,” and he then proceeded to outline the nature of the alternative as foreshadowed by the Paris Commune.

So important did Marx and Engels think the matter to be that in the preface to the 1872 German edition of The Communist Manifesto they noted that “one thing especially was proved by the Commune,” that thing being Marx’s observation in “The Civil War in France” that I have just quoted. It is from these observations that Lenin derived the view that “smashing the bourgeois state” was the essential task of the revolutionary movement.

I have argued elsewhere that in one sense in which it appears to be used in The State and Revolution (and for that matter in “The Civil War in France”) i.e. in the sense of the establishment of an extreme form of council (or “soviet”) democracy on the very morrow of the revolution as a substitute for the smashed bourgeois state, the notion constitutes an impossible projection which can be of no immediate relevance to any revolutionary regime, and which certainly was of no immediate relevance to Leninist practice on the morrow of the Bolshevik revolution; and it is rather hard to blame Allende and his colleagues for not doing something which they never intended in the first place, and to blame them in the name of Lenin, who certainly did not keep the promise, and could not have kept the promise, spelt out in The State and Revolution.

However, disgracefully “revisionist” though it is even to suggest it, there may be other possibilities which are relevant to the discussion of revolutionary practice, and to the Chilean experience, and which also differ from the particular version of “reformism” adopted by the leaders of the Popular Unity coalition.

Thus, a government intent upon major economic, social, and political changes does, in some crucial respects, have certain possibilities, even if it does not contemplate “smashing the bourgeois state.” It may, for instance, be able to effect very considerable changes in the personnel of the various parts of the state system; and in the same vein, it may, by a variety of institutional and political devices, begin to attack and outflank the existing state apparatus. In fact, it must do so if it is to survive; and it must eventually do so with respect to the hardest element of all, namely the military and police apparatus.

The Allende regime did some of these things. Whether it could have done more of them, in the circumstances, must be a matter of argument; but it seems to have been least able or willing to tackle the most difficult problem, that presented by the military. Instead, it appears to have sought to buy the latter’s support and goodwill by conciliation and concessions, right up to the time of the coup, notwithstanding the ever-growing evidence of the military’s hostility.

In the speech he made on July 8 of this year, and to which I referred at the beginning of this article, Luis Corvalan observed that “some reactionaries have begun to seek new ways to drive a wedge between the people and the armed forces, maintaining little less than we are intending to replace the professional army. No, sirs! We continue to support the absolutely professional character of the armed institutions. Their enemies are not amongst the rank of the people but in the reactionary camp.”

It is a pity that the military did not share this view: one of their first acts after their seizure of power was to release the fascists from the Fatherland and Freedom group who had belatedly been put in jail by the Allende government. Similar statements, expressing trust in the constitutional-mindedness of the military were often made by other leaders of the coalition, and by Allende himself.

Of course, neither they nor Corvalan were under much illusion about the support they could expect from the military: but it would seem nevertheless that most of them thought that they could buy off the military; and that it was not so much a coup on the classical “Latin American” pattern that Allende feared as “civil war.”

Regis Débray has written from personal knowledge that Allende had a “visceral refusal” of civil war: and the first thing to be said about this is that it is only people morally and politically crippled in their sensitivities who would scoff at this “refusal” or consider it ignoble. This however does not exhaust the subject. There are different ways of trying to avoid civil war: and there may be occasions where one cannot do it and survive.

Débray also writes (and his language is itself interesting) that “he (i.e. Allende) was not duped by the phraseology of ‘popular power’ and he did not want to bear the responsibility of thousands of useless deaths: the blood of others horrified him. That is why he refused to listen to his Socialist Party which accused him of useless maneuvering and which was pressing him to take the offensive.”

It would be useful to know if Débray himself believes that “popular power” is necessarily a “phraseology” by which one should not be “duped”; and what was meant by “taking the offensive.” But at any rate, Allende’s “visceral refusal” of civil war, as Débray does make clear, was only one part of the argument for conciliation and compromise; the other was a deep skepticism as to any possible alternative. Débray’s account, describing the argument that went on in the last weeks before the coup, has a revealing paragraph on this:

Don Salvador Allende: Chile's martyred president remains a painful memory in the continent's struggle for sovereignty. An object lesson in the perfidy of local elites allied with Washington, and possible hesitancy at a critical moment..

“Disarm the plotters?” “With what?” Allende would reply. “Give me first the forces to do it.” “Mobilize them,” he was told from all sides. For it is true (this is Débray speaking – R.M.) that he was gliding up there, in the superstructures, leaving the masses without ideological orientations or political direction. “Only the direct action of the masses will stop the coup d’état.” “And how many masses does one need to stop a tank?” Allende would reply.

Whether one agrees that Allende was “gliding up there, in the superstructures” or not, this kind of dialogue has the ring of truth; and it may help to explain a good deal about the events in Chile.

Considering the manner of Salvador Allende’s death, a certain reticence is very much in order. Yet, it is impossible not to attribute to him at least some of the responsibility for what ultimately occurred. In the article from which I have just quoted, Débray also tells us that one of Allende’s closest collaborators, Carlos Altamirano, the general secretary of the Socialist Party, had said to him, Débray, with anger at Allende’s maneuverings, that “the best way of precipitating a confrontation and to make it even more bloody is to turn one’s back upon it.”

There were others close to Allende who had long held the same view. But, as Marcel Niedergang has also noted, all of them “respected Allende, the center of gravity and the real ‘patron’ of the Popular Unity coalition”; and Allende, as we know, was absolutely set on the course of conciliation — encouraged upon that course by his fear of civil war and defeat; by the divisions in the coalition he led and by the weaknesses in the organization of the Chilean working class; by an exceedingly “moderate” Communist Party; and so on.

The trouble with that course is that it had all the elements of self-fulfilling catastrophe. Allende believed in conciliation because he feared the result of a confrontation. But because he believed that the Left was bound to be defeated in any such confrontation, he had to pursue with ever-greater desperation his policy of conciliation; but the more he pursued that policy, the greater grew the assurance and boldness of his opponents.

Moreover, and crucially, a policy of conciliation of the regime’s opponents held the grave risk of discouraging and demobilizing its supporters. “Conciliation” signifies a tendency, an impulse, a direction, and it finds practical expression on many terrains, whether intended or not. Thus, in October 1972, the government had got the National Assembly to enact a “law on the control of arms” which gave to the military wide powers to make searches for arms caches.

In practice, and given the army’s bias and inclinations, this soon turned into an excuse for military raids on factories known as left-wing strongholds, for the clear purpose of intimidating and demoralizing left-wing activists — all quite “legal,” or at least “legal” enough.

The really extraordinary thing about this experience is that the policy of “conciliation”, so steadfastly and disastrously pursued, did not cause greater and earlier demoralization on the Left. Even as late as the end of June 1973, when the abortive military coup was launched, popular willingness to mobilize against would-be putschists was by all accounts higher than at any time since Allende’s assumption of the presidency.

This was probably the last moment at which a change of course might have been possible — and it was also, in a sense, the moment of truth for the regime: a choice then had to be made. A choice was made, namely that the president would continue to try to conciliate; and he did go on to make concession after concession to the military’s demands.

I am not arguing here, let it be stressed again, that another strategy was bound to succeed — only that the strategy that was adopted was bound to fail. Eric Hobsbawm, in the article I have already quoted, writes that “there was not much Allende could have done after (say) early 1972 except to play out time, secure the irreversibility of the great changes already achieved (how? – R.M.) and with luck maintain a political system which would give the Popular Unity a second chance later . . . for the last several months, it is fairly certain that there was practically nothing he could do.” For all its apparent reasonableness and sense of realism, the argument is both very abstract and is also a good recipe for suicide.

For one thing, one cannot “play out time” in a situation where great changes have already occurred, which have resulted in a considerable polarization, and where the conservative forces are moving over from class struggle to class war. One can either advance or retreat — retreat into oblivion or advance to meet the challenge.

Nor is it any good, in such a situation, to act on the presupposition that there is nothing much that can be done, since this means in effect that nothing much will be done to prepare for confrontation with the conservative forces. This leaves out of account the possibility that the best way to avoid such a confrontation — perhaps the only way — is precisely to prepare for it; and to be in as good a posture as possible to win if it does come.

This brings us directly back to the question of the state and the exercise of power. It was noted earlier that a major change in the state’s personnel is an urgent and essential task for a government bent on really serious change; and that this needs to be allied to a variety of institutional reforms and innovations, designed to push forward the process of the state’s democratization.

But in this latter respect, much more needs to be done, not only to realize a set of long-term socialist objectives concerning the socialist exercise of power, but as a means either of avoiding armed confrontation, or of meeting it on the most advantageous and least costly terms if it turns out to be inevitable.

What this means is not simply “mobilizing the masses” or “arming the workers.” These are slogans — important slogans — which need to be given effective institutional content. In other words, a new regime bent on fundamental changes in the economic, social, and political structures must from the start begin to build and encourage the building of a network of organs of power, parallel to and complementing the state power, and constituting a solid infrastructure for the timely “mobilization of the masses” and the effective direction of its actions.

The forms which this assumes — workers’ committees at their place of work, civic committees in districts and sub-districts, etc. — and the manner in which these organs “mesh” with the state may not be susceptible to blueprinting. But the need is there, and it is imperative that it should be met, in whatever forms are most appropriate.

This is not, to all appearances, how the Allende regime moved. Some of the things that needed doing were done; but such “mobilization” as occurred, and such preparations as were made, very late in the day, for a possible confrontation, lacked direction, coherence, in many cases even encouragement.

Had the regime really encouraged the creation of a parallel infrastructure, it might have lived; and, incidentally, it might have had less trouble with its opponents and critics on the Left, for instance in the MIR, since its members might not then have found the need so great to engage in actions of their own, which greatly embarrassed the government: they might have been more ready to cooperate with a government in whose revolutionary will they could have had greater confidence. In part at least, “ultra-leftism” is the product of “citra-leftism.”

Salvador Allende was a noble figure and he died a heroic death. But hard though it is to say it, that is not the point. What matters, in the end, is not how he died, but whether he could have survived by pursuing different policies; and it is wrong to claim that there was no alternative to the policies that were pursued. In this as in many other realms, and here more than in most, facts only become compelling as one allows them to be so.

Allende was not a revolutionary who was also a parliamentary politician. He was a parliamentary politician who, remarkably enough, had genuine revolutionary tendencies. But these tendencies could not overcome a political style which was not suitable to the purposes he wanted to achieve.

The question of course is not one of courage. Allende had all the courage required, and more. Saint Just’s famous remark, which has often been quoted since the coup, that “he who makes a revolution by half digs his own grave” is closer to the mark — but it can easily be misused. There are people on the Left for whom it simply means the ruthless use of terror, and who tell one yet again, as if they had just invented the idea, that “you can’t make omelettes without breaking eggs.” But as the French writer Claude Roy observed some years ago, “you can break an awful lot of eggs without making a decent omelette.”

Terror may become part of a revolutionary struggle. But the essential question is the degree to which those who are responsible for the direction of that struggle are able and willing to engender and encourage the effective, meaning the organized, mobilization of popular forces. If there is any definite “lesson” to be learnt from the Chilean tragedy, this seems to be it; and parties and movements which do not learn it, and apply what they have learnt, may well be preparing new Chiles for themselves.

Addendum

Part One of The Battle of Chile, perhaps the best political documentary (certainly the most didactic) ever made. By Chilean director Patricio Guzmán.

[premium_newsticker id="211406"]

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in Deiner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

[google-translator]

[/su_spoiler]

THE DEEP STATE IS CLOSING IN

![]() The big social media —Google, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter—are trying to silence us.

The big social media —Google, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter—are trying to silence us.

THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License