David Walsh and Joanne Laurier

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s part of an eight-film series, Turner Classic Movies, the US cable and satellite television network, presented Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944) at selected theaters on July 19 and 20. It is unusual—and gratifying—in this day and age to watch an older film on the size screen it was intended for.

CLICK IMAGE TO EXPAND TO FUL RESOLUTION

…

Wilder’s film stands up well overall. In terms of its general qualities, Double Indemnityrepresents an example of what American filmmaking could once do: produce a significant artistic work, which expressed an active interest in life and revealed something definite and important about it, that appealed to a wide audience.

Based on a novella by James M. Cain and with a script written by Raymond Chandler (and Wilder), Double Indemnity follows the involvement of insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) with the wife of one of his clients.

A seriously wounded Neff provides a voiceover narration of the sequence of events, in the form of a confession he makes into a Dictaphone machine intended for his superior and friend, Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson).

In a flashback, Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), by her indiscreet questions about taking out accident insurance on her husband, makes it known to Neff that she would like something fatal to happen to Mr. Dietrichson (Tom Powers), a gruff older man whose life and interests seem centered on his work as a site manager in the oilfields.

Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity

After initially rejecting her insinuations, Neff quickly falls in with Phyllis, motivated by both lust and greed. He devises a perfect murder, one that will fool investigators from the insurance company he works for, including Keyes, its top-notch claims adjustor, who boasts that after 26 years in the business he can see through all the “phony” claims that land on his desk.

Neff manages to have Dietrichson sign an application form for the accident insurance without his knowing what he has put his name to. The policy has a “double indemnity” clause, which, as Neff explains to Phyllis, means the insurance companies “pay double on certain accidents. The kind that almost never happen. Like for instance if a guy got killed on a train, they’d pay a hundred thousand instead of fifty.”

Some time later, Neff and Phyllis murder her husband, and arrange things so it seems as though he fell off the back of a moving train. Neff’s company faces having to pay out $100,000 ($1.3 million in current dollars) to Dietrichson’s widow.

Of course the foolproof plot unravels. In fact, as soon as he has committed the murder, Neff knows he is finished. He explains in his voiceover: “Nothing had slipped, nothing had been overlooked, there was nothing to give us away. And yet, Keyes … suddenly it came over me that everything would go wrong. It sounds crazy, Keyes, but it’s true, so help me: I couldn’t hear my own footsteps. It was the walk of a dead man.”

The difficulties arise from several sources. In the first place, Keyes has the intuition that “there’s something wrong with that Dietrichson case,” although he can’t pinpoint what it is to begin with. Moreover, Phyllis’s stepdaughter, Lola (Jean Heather), has well-grounded suspicions about her stepmother. The most destabilizing factor of all, however, is the moral-psychological dilemma the two accomplices of murder find themselves in.

As Keyes later explains to Neff, assuming that one of Dietrichson’s killers is Phyllis and not yet knowing that the other is his younger colleague: “Their [the murderers’] emotions are all kicked up. Whether it’s love or hate doesn’t matter. … They’re stuck with each other. They’ve got to ride all the way to the end of the line. And it’s a one-way trip, and the last stop is the cemetery.”

Neff and Phyllis eventually fall out, with predictably tragic results. In their final encounter, at which each plans to eliminate the other, part of the exchange goes like this:

PHYLLIS: We’re both rotten, Walter.

NEFF: Only you’re just a little more rotten. You’re rotten clear through. You got me to take care of your husband, and then you got Zachetti to take care of Lola [Zachetti is Lola’s boyfriend], and maybe take care of me too, and then somebody else would have come along to take care of Zachetti for you. That’s the way you operate, isn’t it, baby?

PHYLLIS: Suppose it is, Walter. Is what you’ve cooked up for tonight any better?

She shoots him in the shoulder, but is unable to finish him off. He takes the gun out of her hand.

NEFF: Why didn’t you shoot, baby? [“Phyllis puts her arms around him in complete surrender.”] Don’t tell me it’s because you’ve been in love with me all this time.

PHYLLIS: No. I never loved you, Walter. Not you, or anybody else. I’m rotten to the heart. I used you, just as you said. That’s all you ever meant to me—until a minute ago. I didn’t think anything like that could ever happen to me. …

NEFF: Goodbye, baby.

He then shoots her twice.

Double Indemnity proceeds with great intensity from the opening credits, in which the silhouetted figure of a man on crutches approaches the camera (a reference to the eventual murder sequence) against composer Miklós Rózsa’s ominous score, to its opening sequence of an automobile traveling erratically through downtown Los Angeles’ nighttime streets before stopping in front of an office building …

The urgency and tension persist over the course of the entire film.

Seventy years after its release, Double Indemnity remains an intriguing, entertaining and complex work. The precision of the dialogue, acting, cinematography and editing stands in sharp contrast to most of our contemporary films, which look like amateurish, self-indulgent trivia against Wilder’s film.

In the first place, the filmmakers collectively had something to say about American life, and specifically life in Southern California. Billy Wilder, born in what was then Austria-Hungary, Raymond Chandler, educated in England, and James M. Cain, from the East Coast, brought a certain “outsider’s” perspective to the work.

James M. Cain

Cain loosely based his novella—first published in serial form in 1936 and then in a collection of three short novels in 1943—on a notorious 1927 murder committed in Queens, New York by the wife of the victim and her boyfriend, both of whom were eventually executed. A “double indemnity” insurance policy was involved in the case.

Critic Edmund Wilson termed Cain one of “the poets of the tabloid murder,” noting further that “Such a subject might provide a great novel: in [Theodore Dreiser’s] An American Tragedy, such a subject did.” While acknowledging the genuine gifts of the hardboiled Cain (influenced by Dreiser, as well as Ernest Hemingway), who possessed “enough of the real poet,” Wilson criticized the presence in his work “of something we know all too well: the wooden old conventions of Hollywood.”

In fact, Double Indemnity is a weaker effort than Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, Serenade or Mildred Pierce, truly going off the rails toward the end. The Stanwyck character’s counterpart in the novel, Phyllis Nirdlinger, proves to be genuinely psychotic and the author engages in more than his share of dime-store psychologizing.

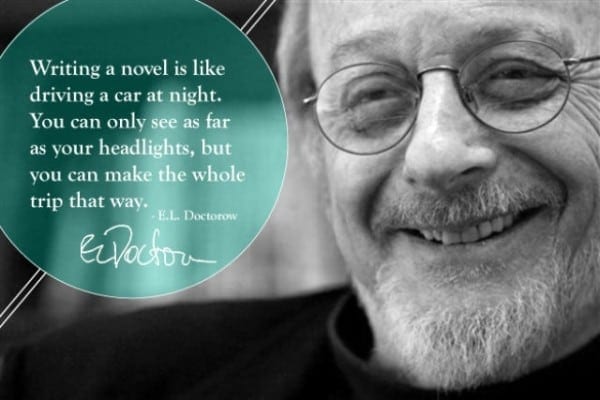

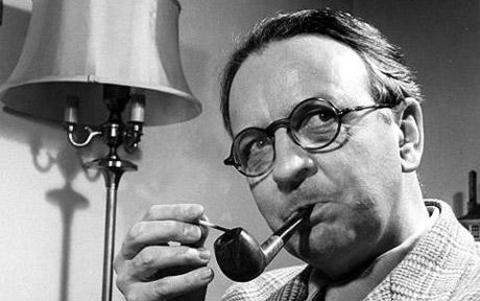

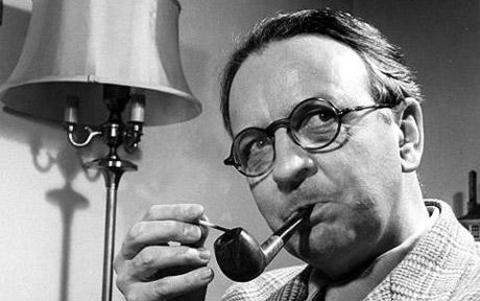

Raymond Chandler

Cain later admitted that the screenplay by mystery writer Chandler (The Big Sleep; Farewell, My Lovely; The High Window; The Lady in the Lake; The Little Sister; The Long Goodbye), with help from Wilder, was an improvement on his original novel. Chandler knocked much of the extraneous and distracting material out of the story, while retaining its critical focus on the doomed couple thrashing hopelessly about against the backdrop of sunny Southern California and the implacable workings of the insurance business.

…

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]ilder brought his own strengths to the work. Born to a Jewish family in Sucha Beskidzka, Austria-Hungary, which is today in southern Poland, Wilder moved with his family to Vienna and later, to pursue a career as a journalist, he settled in Berlin. Wilder began working as a screenwriter and in 1929 he wrote the script for People on Sunday (Menschen am Sonntag), which follows a group of ordinary Berlin residents over the course of one weekend. Remarkably, other participants on the 73-minute film included future Hollywood directors Robert Siodmak, Fred Zinnemann and Edgar G. Ulmer, screenwriter Curt Siodmak and famed cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan.

Wilder left Nazi-ruled Germany one day after the Reichstag fire in February 1933, eventually making his way, a year later, to the US. As Wilder subsequently noted, he and other refugees from Germany of his generation did not arrive in Hollywood “because we were invited … we came to save our lives.” The entire Jewish population of Wilder’s native town, including his mother, grandmother and stepfather, perished in the Holocaust.

Billy Wilder in 1942

Wilder spoke only a few words of English when he began work in the film industry. In 1936, Paramount executives teamed him with screenwriter Charles Brackett and the pair produced a number of primarily comic scripts for Ernst Lubitsch (Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife, Ninotchka), Mitchell Leisen (Midnight, Hold Back the Dawn) and Howard Hawks (Ball of Fire). Wilder got his first directorial assignment with The Major and the Minor(1942), featuring Ginger Rogers, pretending to be a 12-year-old to save train fare, and Ray Milland. Double Indemnity was only his third feature film as director.

The typical Hollywood production in the 1940s could call on an immense pool of talent and professional experience, consisting in many cases of individuals with serious artistic biographies. One should not of course forget the performers themselves, Stanwyck and Robinson, two of the finest film actors of all time, MacMurray, who effectively played “against type” in Double Indemnity(Wilder had great difficulty casting the role of the villainous Neff), and Porter Hall, Richard Gaines and Powers in smaller roles.

As noted above, the film’s music was composed by the Budapest-born and Leipzig-trained Rózsa, who wrote scores for nearly 100 films, as well as many classical pieces. Cinematographer John Seitz, whose career extended back into the days of silent films provided low-key lighting and the “newsreel style” photography, influenced by the wartime conditions. “We attempted to keep it extremely realistic,” he said.

Paramount’s art department, headed by the German-born Hans Dreier and represented on Double Indemnity by Hal Pereira (who would go on to work on 270 more films, including many of Alfred Hitchcock’s major films in the 1950s), made its own contribution. Both the Dietrichson home and Walter Neff’s apartment suggest drabness, depression and a lack of generosity or warmth. These are locations where people live among inanimate objects and other people to which or to whom they have little or no connection.

The head office of the Pacific All-Risk Insurance Company, which employs Neff and Keyes, is grim and confining in its own way. From a balcony that runs all the way around the floor that houses the executive offices and claims and sales departments, according to the script, we see the floor below: “one enormous room filled with [identical] desks, typewriters, filing cabinets, business machines, etc.”

The company president, Norton (Gaines), occupies “the best office in the building; modern but not modernistic, spacious, very well furnished; flowers, smoking stands, easy chairs, etc.” In fact, that “spaciousness” comes in for an ironic reference. Having summoned Keyes and Neff to his office to discuss the Dietrichson claim, Norton launches into his theory of the case by announcing, “There’s a widespread feeling that just because a man has a large office … he must be an idiot,” which, naturally, he proves to be.

There are weaknesses in Double Indemnity. The rapid transformation of Walter Neff from smirking, wisecracking salesman into cold-blooded murderer is never properly or convincingly motivated. Nor is there the explosive chemistry between MacMurray and Stanwyck that the storyline seems to require. The most spontaneous and warmest relationship in the film, as various commentators have noted, takes place between Neff and Keyes.

Critic Andrew Sarris sought to justify some of the psychological implausibility inDouble Indemnity by pointing to “Wilder’s tendency to jump the gap between motivation and action by using very personal feelings of guilt and corruption,” but isn’t that merely a diplomatic way of indicating that Wilder is not an artist of the most patient and profound order?

This is not An American Tragedy. That novel takes some 500 dense and highly charged pages to arrive at its death scene, and by that time, from the point of view of selfish, social-climbing lead character Clyde Griffiths, killing Roberta Alden, his pregnant, working class girlfriend, or at least allowing her to drown, appears to be the only logical course of action. The determinism of Dreiser’s novel, rooted in a tremendous understanding of American society, is devastating and unimpeachable.

Neither the Cain novella nor the Chandler-Wilder film is committed to such a ferocious critique, although the futility and destructiveness of pursuing the American Dream of material success at any cost is certainly a theme here.

The filmmakers’ principal concerns lie with other, perhaps related features of American life.

In the first place, Double Indemnity depicts a mercenary social world in which the possibility of murdering Dietrichson or someone like him for insurance money arises almost organically.

Edward G. Robinson (Adjustor Keyes) and Fred MacMurray (the antihero Walter Neff) in Double Indemnity

After all, the everyday calculations made by Pacific All-Risk are just as unfeeling and brutal as Neff and Phyllis’s own. The insurance company makes wagers on life and death and coins vast profits from the insecurities and dangers of modern existence. (“NEFF: Anything wrong? KEYES: The guy’s dead, we had him insured and it’s going to cost us money. That’s always wrong.”)

Moreover, the murder of Dietrichson also fits seamlessly into things in the sense that it speaks to a type of American pragmatic shortsightedness, perhaps the weakest side of the national character. There may be an immediate psychic improbability in Neff’s actions, which weakens the art, but there is a broader social probability.

Both Neff and Phyllis are chasing a “quick fix” and a “quick buck.” They want to make a fortune by taking a shortcut. Doing away with Dietrichson, who has not committed any crime against either one of them, and collecting the insurance payoff appeals to their essential laziness. The killing arises as the practical solution to a problem. It seems, in some sordid fashion, the easiest and most “natural” thing to do. Neff has to expend some brain power coming up with a plan, but the murder itself does not appear to require any more special effort than drinking a beer at a drive-in restaurant (where a waitress brings the beer to his car window) or bowling “a few lines” at a local bowling alley, other activities we see him engaged in.

The crime, meticulously prepared and over in an instant, somehow figures into the contemporary, efficient pace of American life. In his valuable More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts, James Naremore observes that Double Indemnity owes much of its imagery to “Fordist” America: “On the level of language alone, as William Luhr points out, the film is pervaded with grimly deterministic metaphors of modern industry: the lovers promise to remain committed to one another ‘straight down the line’; Walter devises a clockwork murder involving a train, and when he puts his plan in motion he remarks that ‘the machinery had started to move and nothing could stop it’; later, looking back over his crime, he claims that fate had ‘thrown the switch’ and that the ‘gears had meshed.’”

Inevitably, Neff and Phyllis’s plan to dispatch their victim in a well-oiled, dispassionate manner, their dream of a homicide without “after effects,” proves delusional and catastrophic. Neff explains: “I killed him for money and for a woman. I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman. Pretty, isn’t it?” As though you could kill another human being and suffer no consequences, moral or otherwise!

Their plot also runs up against the need of the state apparatus to maintain law and order, including a monopoly on the ability to put people to death. The assembly line, including for the purposes of execution, only operates for the benefit of those who run capitalist society.

In the initial version of the film, Neff became a victim of the American assembly line of death. A final scene, that Wilder actually shot, took place in San Quentin prison, from the point of view of the witness room in the death chamber. Naremore writes: “Paramount built an exact replica of the gas chamber, depicting it as a modern, sanitized apparatus for administering official death sentences.”

Neff and Keyes in the final gas chamber scene. The final cut eliminated this segment.

Keyes watches as Neff is brought into the gas chamber. The original script continues: “The executioner and one guard close the door. The guard spins the big wheel which tightens it. The wheel at first turns very quickly, then, as it tightens, the guard uses considerable force to seal the chamber tight. The guard steps out of the shot. The gas chamber is now sealed.”

Although the viewer would not have seen Neff undergo the agony of death, the camera took in all the horrific preliminaries, including the actions of the “acid man,” who “releases the mixed acid into a pipe connecting with a countersunk receptacle under Neff’s chair.” The executioner then pushes a metal lever that “immerses the pellets of cyanide in the acid under the chair.”

As the gas floats up into the air in the chamber, “Keyes, unable to watch, looks away.” The script describes the final shot of Keyes leaving the prison in these words: “Suddenly he stops, with a look of horror on his face. … When he has almost reached the door, the guard stationed there throws it wide, and a blaze of sunlight comes in from the prison yard outside. Keyes slowly walks out into the sunshine. stiffly, his head bent, a forlorn and lonely man.”

Wilder agreed to suppress the scene, apparently under pressure “from both the studio and the Breen Office [Hollywood’s censors], which insisted that the gas chamber sequence was ‘unduly gruesome’” (Naremore). Wilder later justified his decision on the ground that the scene was unnecessary. He may have been right.

In any case, Naremore adds: “The grimmest irony of Double Indemnity, which he [Wilder] did not know at the time, was that his own mother had been gassed at Auschwitz only a year or two before the film began production.” Historical research now apparently indicates that Wilder’s mother was murdered at another camp, but that hardly alters the matter.

Film noir

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]ilder’s Double Indemnity is often held up as a classic example of Americanfilm noir, a term invented by French critics meaning “black” or “dark film.” The production of the most meaningful cluster of such films occurred between the end of World War II and the early 1950s.

Whether film noir is a genre or style or a sub-genre is an academic and not very interesting question. More important is the fact that the thoughts and feelings that went into hundreds of films during this period reflect similar and complex moods.

In the most general sense, film noir reflected, through the peculiar prism of the American popular entertainment business, the accumulated, intensely contradictory artistic response to the immense events of the first half of the 20th century, the slaughter of two world wars, the Russian Revolution and the growth of Stalinism, the Great Depression, the rise and ultimate collapse of fascism, a response that combined optimism and despair, left-wing opposition and cynicism, a sense of social solidarity and pronounced individualism, defiance and fatalism.

On the one hand, the widespread radicalism of the 1930s and the great combativity of the American working class at the end of the war, illusions in Roosevelt and the New Deal and in the possibility of expanding “Popular Front” or “socialistic” policies in the US, and the continued existence and military successes of the Soviet Union, buoyed the left filmmakers and permitted a cautious optimism about the future. The residual effect of socialist thought in the American intelligentsia was still a factor at this time.

On the other, the horrors of Nazism and the Holocaust, and, to the extent that the artists were honest with themselves, the brutality of the Allied powers’ fire-bombing of Dresden and other German cities and the annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki led many in the direction of despair.

Naremore comments that “postwar thrillers also seemed more downbeat and perverse, perhaps because the war and its aftermath created a vision of ontological evil and a growing appetite for sadism.” He observes that Hollywood now regularly portrayed fascist or militarist “killers who loved to inflict pain” and that this imagery “contributed to the psychotic villains portrayed at almost the same time by Richard Widmark, Dan Duryea, and Raymond Burr. Because of the war, screen violence also became more frighteningly realistic. … As the fighting drew to an end, the sense of victory was bound up with a vision of horror.”

One has only to compare the relatively straightforward gangster films of the late 1930s and early 1940s, like Each Dawn I Die, I Stole a Million, The Roaring Twenties, You Can’t Get Away with Murder, even High Sierra, with the tortured products of the late war and immediately postwar (and pre-blacklist) years (1944-47), such as Double Indemnity, The Woman in the Window, Detour, Mildred Pierce, The Blue Dahlia, The Killers, The Postman Always Rings Twice, Born to Kill, Brute Force, Kiss of Death and Out of the Past, to see the marked difference.

On balance, however, the best film noir works are pleasurable and intriguing, first, because an attitude of social resistance, distrust of the authorities and sympathy for the underdog predominates. And this attitude is conveyed, as in Double Indemnity, with breath-taking vigor, directness and urgency.

Naremore’s More Than Night makes the important point, contrary to the self-serving argument of certain film historians that film noir was characterized by a “hopeless” and “relentlessly cynical” mood, that “most of the 1940s directors subsequently associated with the form—including Orson Welles, John Huston, Edward Dmytryk, Jules Dassin, Joseph Losey, Robert Rossen, Abraham Polonsky, and Nicholas Ray—were members of Hollywood’s committed left-wing community.” And many other filmmakers of the time, including Michael Curtiz, Fritz Lang, Edgar Ulmer, Max Ophuls, Robert Siodmak, Anthony Mann, Andre de Toth, John Farrow, Raoul Walsh, Joseph H. Lewis and later Robert Aldrich were hardly untouched by oppositional or rebellious sentiments.

Among the writers that would be an even more pronounced tendency. The wartime, during which the US was allied to the Soviet Union, and its immediate aftermath marked the high point of Communist Party influence, among the screenwriters. [S]upport for the CP obviously indicated a desire, however confused or misdirected, for significant social change.

There is a complex but real correspondence between the overall feeling communicated by the films of this era and the sentiments of millions. With the war over and fascism dispatched by themselves and people like themselves, wide layers of the American population had no intention of being driven back to the miseries and humiliations of the Depression. A strong and confident desire existed to tackle life, even if the horrors of the war and fascism had saddened and deepened mass sentiment, made it more complex and troubled, “less surprised” and more mature. Great events, as Trotsky once noted, do not elapse in vain, they bring with them great experiences.

The finest films of this period, including Double Indemnity, suggest that despite the dark streets and sometimes cruel and nightmarish goings-on, despite the possibility of betrayal and bitter disappointment, reality is not something to be evaded, shied away from or mystified.

Unlike the vast majority of current films, Double Indemnity both merits and requires serious thought. The words and images here make a lasting impression, they simultaneously entertain and disturb. Wilder’s film is flawed, but it retains its force and speaks not only to a particular historical moment but to persisting characteristics of American life.

David Walsh and Joanne Laurier are senior cinema critics with wsws.org.

FACT TO REMEMBER:

IF THE WESTERN MEDIA HAD ITS PRIORITIES IN ORDER AND ACTUALLY INFORMED, EDUCATED AND UPLIFTED THE MASSES INSTEAD OF SHILLING FOR A GLOBAL EMPIRE OF ENDLESS WARS, OUTRAGEOUS ECONOMIC INEQUALITY, AND DEEPENING DEVASTATION OF NATURE AND THE ANIMAL WORLD, HORRORS LIKE THESE WOULD HAVE BEEN ELIMINATED MANY YEARS, PERHAPS DECADES AGO. EVERY SINGLE DAY SOCIAL BACKWARDNESS COLLECTS ITS OWN INNUMERABLE VICTIMS.

[printfriendly]

REBLOGGERS NEEDED. APPLY HERE!

Get back at the lying, criminal mainstream media and its masters by reposting the truth about world events. If you like what you read on The Greanville Post help us extend its circulation by reposting this or any other article on a Facebook page or group page you belong to. Send a mail to Margo Stiles, letting her know what pages or sites you intend to cover. We MUST rely on each other to get the word out!

And remember: All captions and pullquotes are furnished by the editors, NOT the author(s).

What is $5 a month to support one of the greatest publications on the Left?

![]()