With Syriza approaching the gates of power in Greece, the Internet has been full of analyses, opinion pieces, and endorsements and denunciations. In this interview with Stathis Kouvelakis conducted earlier this month, we take a critical distance to understand the origins, trajectory, and possible challenges of this political formation.

To do this, we have not hesitated to delve into some of the internal complexities of the astonishingly diverse Greek radical left. But Kouvelakis also talks to us about some of the immediate and concrete challenges that will face the party once in power.

Lenin Reloaded and Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism. He was interviewed for Jacobin by Sebastian Budgen, an editor for Verso Books who serves on the editorial board of Historical Materialism.

Tell us about Syriza: when and how did this coalition of radical left parties come into being?

Syriza was set up by several different organizations in 2004, as an electoral alliance. Its biggest component was Alexis Tsipras’s party Synaspismos — initially the Coalition of the Left and Progress, and eventually renamed the Coalition of the Left and of the Movements — which had existed as a distinct party since 1991. It emerged from a series of splits in the Communist movement.

On the other hand, Syriza also comprises much smaller formations. Some of these came out of the old Greek far left. In particular, the Communist Organization of Greece (KOE), one the country’s main Maoist groups. This organization had three members of parliament (MPs) elected in May 2012. That’s also true of the Internationalist Workers’ Left (DEA), which is from a Trotskyist tradition, as well as other groups mostly of a Communist background. For example, the Renewing Communist Ecological Left (AKOA), which came out of the old Communist Party (Interior).

The Syriza coalition was founded in 2004, and at first it had what we might call relatively modest successes. Nevertheless it managed to get into parliament, overcoming the 3 percent minimum threshold. To cut a long story short, Syriza resulted from a relatively complex recomposition of the Greek radical left.

Since 1968, the radical Left had been divided into two poles. The first was the Greek Communist Party (KKE), which itself underwent two splits: the first, in 1968, under the colonels’ dictatorship, which gave rise to the KKE (Interior), which was of a Eurocommunist bent, and a second one in 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The Eurocommunist party underwent a split in 1987, with its rightist wing constituting the Greek Left (EAR) and joining Synaspismos from the outset, and the leftist one reforming as the AKOA. The KKE that remained after these two splits was peculiarly traditionalist, clinging on to a Stalinist framework that became considerably more rigid after the 1991 split. The party was rebuilt on a both combative and sectarian basis. It managed to win a relatively significant activist base among working-class and popular layers, as well as among the youth, particularly in the universities.

The other pole, Synaspismos, opened out in 2004 with the creation of Syriza, which itself came from the joining together of the two previous splits from the KKE. Synaspismos has changed considerably over time. At the beginning of the 1990s, it was the kind of party that could vote for the Maastricht Treaty, and it was mainly of a moderate left coloration.

But it was also a heterogeneous party composed of various distinct currents. Very hard-fought internal struggles pitted the left wing of the party against the right wing, and the right wing gradually lost control. The foundation of Syriza sealed Synaspismos’s turn to the left.

What is the influence of the Communist tradition on Synaspismos?

The Communist matrix is clearly perceptible in the majority culture of the party. One part came out of the Eurocommunist-influenced tendency that opened up to the new social movements from the 1970s onward. It thus proved able to renew its organizational and theoretical reference points, grafting the traditions of the new forms of radicalism onto its existing Communist framework.

It is a party that’s at ease among feminist movements, youth mobilizations, alter-globalization, and antiracist movements and LGBT currents, while also continuing to make a considerable intervention in the trade union movement. Another part comes from the layer of cadres and members that left the KKE in 1991, the largest part of them being now in the Left Current, although many members of the majority group of the leadership and of the cadres, also come from that strand.

We should note that the party’s cadres and activist base are mainly educated wage earners — people with degrees. It is a very urban electorate, a party with very strong roots among intellectuals. Until very recently Synaspismos had an absolute majority in the higher education union, unlike the KKE, which has lost since the 1989–1991 splits any kind of privileged relation with intellectual circles.

The party leadership also bears a Communist stamp. Don’t be fooled by Tsipras’s age: he himself started out as an activist in the KKE youth organization, in the early 1990s. Many of the oldest cadres and leaders fought side-by-side in the clandestine period, and are veterans of prisons and deportation camps.

For this very reason there is a fratricidal atmosphere on the Greek radical left, though currently it is the KKE alone who keeps it going — branding Synaspismos and then Syriza as “traitors” who thus represent its “main enemy.” That’s why when Syriza established bilateral relations with almost all the parties represented in parliament after the May 2012 elections — when it had the right to try and form a government — the KKE refused even to meet with them.

And how would you characterize Syriza’s line? Would you also say that this coalition is following an anticapitalist line, or is its activity part of a more gradual, reformist approach?

In terms of its programmatic and ideological identity, Syriza has a strong anticapitalist line, and it has very sharply set itself apart from social democracy. That consideration is all the more important if we think about the history of the battles within Synaspismos that pitched tendencies who were favorable to allying with social democrats against other currents who were hostile to any sort of agreement or coalition, including at the local level or in trade union activity.

The “social democratic” wing of Synaspismos definitely lost control of the party in 2006 when Alekos Alavanos was elected its president. This right wing, led by Fotis Kouvelis, almost exclusively originating in the Eurocommunist right group coming from EAR, ultimately left Synaspismos and set up another party called Democratic Left (Dimar): a formation that claims to be a sort of halfway house between Pasok and the radical left.

So Syriza is an anticapitalist coalition that addresses the question of power by emphasizing the dialectic of electoral alliances and success at the ballot box with struggle and mobilizations from below. That is, Syriza and Synaspismos see themselves as class-struggle parties, as formations that represent specific class interests.

What they want to do is advance a fundamental antagonism against the current system. That’s why it’s called “Syriza”: meaning, “coalition of the radical left.” And this assertion of radicalism is an extremely important part of the party’s identity.

What are the relations of force among Syriza activists, and how many people are there in each of the formations that make up this coalition?

In 2012, Synaspismos had around 16,000 members. The Maoist KOE had about 1,000-1,500 activists, and you can say more or less the same for AKOA. Synaspismos’s practice and organizational form have developed in tandem with its ideological positioning. Traditionally it was not an party of activists at all, instead it had a lot of big names and an essentially electoral orientation. But the party’s organizational substance and activism have changed considerably, at two different levels.

Firstly, a very dynamic youth wing developed during the alter-globalization and antiracist movements. This allowed the party to strengthen its youth presence, particularly among students, an area where it had traditionally been lacking. Its youth organization now has many thousands of members. Indeed, cadres who have come from this youth wing make up a good part of Tsipras’s entourage. They are characterized by real ideological radicalism, and they identify with Marxism, mostly of an Althusserian hue.

Secondly, trade unionists took on more of a role in Synaspismos in the 2000s, becoming the anchor of the party’s left wing. Largely coming from the KKE, this left wing is a more working-class element that stands for relatively traditional class-struggle positions and is very critical of the European Union.

That is not to say that there are no longer any moderates in the party today. In particular we could think of leading economics spokesman Yannis Dragasakis and some of the cadre who used to be close to Fotis Kouvelis but refused to follow him out of the party into Dimar.

You said that thus far Syriza has had an essentially urban activist and electoral base. Did this change with Syriza’s electoral breakthrough in May 2012, where it became the second party in Greece with 16.7 percent of the vote, beating Pasok?

Absolutely so. Understanding the sociology of the 2012 Syriza vote is of decisive importance. The qualitative transformation is just as seismic as the quantitative leap. It’s relatively easy to understand what happened in May and June 2012 — it was essentially a class vote. The wage-earning working-class voters of the main urban centers, who had mainly used to vote Pasok, abruptly broke in favor of Syriza.

Syriza came first in greater Athens, in which around a third of the Greek population lives, as well as in all the main urban centers, and now controls the elected “regional council” since last May’s local elections. It achieved its best scores in working-class and popular districts that used to be Pasok — and also KKE — strongholds.

The KKE’s decline began in these constituencies, and it’s going to get worse. We have seen KKE voters going over to Syriza. This is a working-class vote, but also a vote from educated employees — a vote from people active in the labor market. Syriza’s score among eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds and twenty-four- to thirty-year-olds was close to its overall national average, but among the layers that make up the core of the working population (thirty-plus) it did better than its average.

Its weakest scores were among the economically inactive, the rural population (including the peasantry), pensioners, housewives, the self-employed, and independent professionals. So the dynamic of Syriza support is based on a wage-earning class vote — including its upper strata — popular layers, and unemployed people in Greece’s main urban centers.

To what extent is Syriza’s support based on public-sector workers?

Electoral sociology shows that Syriza got in June 2012 33 percent of public sector workers’ votes and 34 percent in the private sector: so more or less similar scores, with slightly more support among public-sector workers if we consider the evolution of the vote between June 2012 and last May’s European elections. But its very best results were in the second Piraeus constituency — a major industrial and working-class constituency — as well as in the Xanthi province in northern Greece, among the majority-Muslim and Turkish-speaking population. Indeed two Syriza MPs from the Turkish-speaking Muslim minority were was elected for this area.

How do you explain Syriza’s sudden electoral success in 2012?

There are three factors to consider. The first lies in the violence of the social and economic crisis in Greece and the way it developed from 2010 onward, with the austerian purge that has been inflicted under the infamous memorandums of understanding (the agreements the Greek government signed with the troika in order to secure the country’s ability to pay off its debts).

The second factor resides in the fact that Greece — and now also Spain — are the only countries where this social and economic crisis has transformed into a political crisis. The old political system, which was based on a very stable two-party duopoly, has collapsed.

The third factor is popular mobilization. It’s not a coincidence that the two European countries where the radical left has taken off are Greece and Spain, namely the countries that have seen the strongest popular mobilizations in recent years. In Spain they had the indignados movement, whereas in Greece there was a deeper and socially more diverse movement.

Most of the forces that have freed themselves of the traditional forms of political representational binds have turned toward the radical Left, while part of society that has remained outside of this dynamic has turned to abstention, which also rose very significantly since the start of the crisis, or toward the extreme right, namely the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party.

But Syriza’s electoral and political success is explained more precisely by the fact that the party has opposed the memorandums and austerity shock therapy from the outset. This is because after long debates, especially within Synaspismos, Syriza had rejected the idea of alliances with the Pasok ever since its creation as a coalition.

And due to its “movementist” sensibility, it has proven concretely and practically able to commit itself to the social movements and collective actions that have taken place in Greece in recent years. It has done so at the same time as respecting these movements’ autonomy, including the most novel and spontaneous forms of mobilization. For example, it supported the city square occupations movements we saw in 2011, whereas KKE denounced this movement as “anti-political” and accused it of being dominated by petty-bourgeois and anticommunist elements.

It is a party that has also done much for solidarity networks at a local level, in order to deal with the traumatic social crisis and its concrete effects on people’s everyday lives. It is also a formation that has enough visibility in the institutions to seem capable of transforming the balance of forces at the level of national political life.

That said, Syriza took off in the opinion polls only in the last few weeks of the 2012 electoral campaign. The real breakthrough came when Tsipras focused his discourse on the theme of constituting an “anti-austerity government of the Left” now, which he presented as an alliance proposal reaching out to the KKE, the far left, the parliamentary left, and the small dissident elements of Pasok.

That’s what literally changed the course of the electoral campaign, setting a whole new agenda. That was when we began to hear a stir — it was almost something physical — and Syriza’s polling numbers soared. From that moment onward, the other parties had to react to Syriza’s offer, which had emerged as a concrete political perspective — indeed, one within reach — allowing Greece to shake off the yoke of the memorandums and the troika.

That’s a very ecumenical approach, for the Left . . .

Yes, indeed. Syriza is a particularly credible source for this kind of proposal because of its practice in the social movements, but also on account of its own internal makeup. That is, it is a political front, and even within Syriza there is a practical approach allowing the coexistence of different political cultures. I would say that Syriza is a hybrid party, a synthesis party, with one foot in the tradition of the Greek Communist movement and its other foot in the novel forms of radicalism that have emerged in this new period.

Do you think that the social movement that we saw with the city square occupations in Greece is linked to Syriza’s advances at the ballot box?

Absolutely. Some people believed that these movements were not only spontaneous but even anti-political, that they stood outside and against politics. But while they did indeed reject the politics they saw in front of them, they were also looking for something different. The Podemos experience in Spain as well as Syriza in Greece shows that if the radical Left makes suitable proposals, then it can arrive at an understanding with these movements and provide a credible political “condensation” of their demands.

What are Syriza’s concrete experiences of local and regional government since 2012?

From the 1990s–2000s the radical left set itself against any alliances with Pasok, and for that reason neither Syriza or the KKE were involved in regional governments, and in very few local authorities either, until recently. Now there is a sharp contrast between the breakthrough Syriza has made at the national and European level and its local implantation.

The party scored less at the local and regional polls — which took place on May 25, 2014 — than it has in the national and European elections: 18 percent instead of 27 percent. But nonetheless it did make major advances, with two regions going to Syriza, including Attica, where nearly 40 percent of the Greek population lives.

How is Alexis Tsipras seen in Greece?

The foremost aspect of Tsipras’s image is his age: he is a young man, after all. But the Greek radical left’s cadres and leadership groups are still dominated by a generation approaching its sixties, or even older people who still enjoy the prestige of having been involved in the struggle against the colonels’ dictatorship.

Alekos Alavanos, who used to be the Synaspismos president, organized the handing of control to Tsipras in order to mark a break with this kind of generational sclerosis. It was a great act of political will. Tsipras is popular because even before being elected to the Synaspismos leadership, he topped the party list in the Athens municipal elections.

He is not exactly a charismatic tribune. He is not a bad public speaker either, but certainly he doesn’t have the oratorical talent of a George Galloway or Jean-Luc Mélenchon. He has also made some mistakes, particularly insofar as he, like a lot of the Greek radical left, initially underestimated the depth of the crisis and the extent to which the question of public debt would be used to justify the implementation of austerity measures.

He has changed the image of the Greek radical left, which right up till now was always considered a considerable, important, or useful part of social movements but not as a force that sought to take on the historic responsibility of offering a way out of the crisis. This is a real turnaround for a radical left that is still traumatized by the defeat of twentieth-century communism. And today it wants to leave behind its role as an eternal minority — the role of a force doomed to perpetually just “resisting.”

Could you update us on any figures you have about the relative strength of Syriza in terms of membership and its social weight since 2012, and then say more about the internal dynamics of Syriza, the left platform, different constituent elements of that — and also the opposing side, the center, and the right?

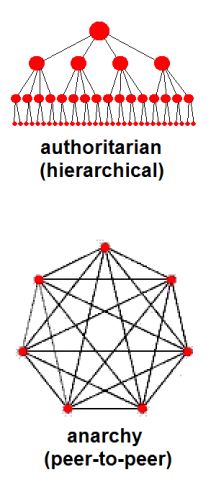

Immediately after the 2012 elections, the process of unification of what was as until then a coalition of parties started. First with a national conference, which elected for the first time a leadership body and then the founding congress of Syriza in July 2013. I think that some important decisions concerning the structure of the party, and what we could qualify as the party form, were made at that stage, but the priority was to have a speedy process, which didn’t leave time for a proper in-depth political discussion.

At the same time, and it was a process of opening up, but it was a process of opening up without addressing specific social constituencies and layers of people involved in social movements. So it was more or less a process leading more to a party of members than a party of activists or active members, a parti d’adhérents rather than a parti de militants. Which also means that this rendered Syriza as an organization to a certain extent permeable to the practices of, if not clientelism, at least the practice of local, traditional networks of power, which are still very strong in Greek society.

The establishment parties have been de-structured at the national level. They do not exist as centralized parties, or hardly so. Pasok has completely disintegrated and it was by far the most powerful party machine in Greece, and because New Democracy, which used to be a rightwing mass organization, is also very seriously weakened, but the networks linked to these parties are still very strong at the local level. We saw that in the last local elections, for instance, where the gap between the local electoral influence of Syriza and the capacity to win local councils is very, very significant.

The other negative feature of the new structure is that Syriza has become clearly a leader-centered party, and this is accentuated by the fact that the internal structures are very numerous, dysfunctional, and they tend less and less to function as real centers of policymaking or of decision making. The whole process of decision making has become actually more centralized, more opaque, with the leader playing a very crucial role, combined with various informal leadership circles, rather than a collective leadership, or even a more restricted group of leaders.

One of the aims, I think, which was pursued by the party leadership was to marginalize the left tendencies within Syriza. They very seriously thought that we were relatively strong in the old Syriza (in the pre-2012 Syriza), which was organized as a coalition, a constellation of various parties, but with the influx of new members, our relative weight would diminish drastically inside the party.

To give you an example, which is more specifically about the biggest — by far — component of Synaspismos: at the last congress of the party, the congress in which Dimar departed, the left current, led by Alavanos, got about 25 percent of the vote.

So when the Left Platform got 25 percent at the November 2012 inaugural National Conference of Syriza, it came as a big surprise to the leadership. It was an even bigger surprise for them that the Left Platform increased its relative weight in the founding congress of Syriza and got over 30 percent.

In between, the membership of Syriza approximately doubled, and it remains stable around these figures, an increase from about 17,000–18,000 members to 35,000–36,000. It developed geographically quite significantly, but the gap between the electoral influence and the organized force is still huge, and the links between the party and the core of its electorate — the urban working class, essentially — remain weak.

Syriza is still dominated very much by intellectual layers: public-sector workers with a high level of skills and education. In terms of age, it is also quite problematic: the relative weight of the younger layers remains quite limited.

Is there a youth wing?

Yes, there is a specific youth wing, which is the outcome of the unification of the youth wings of all the components of Syriza, but it remains relatively small compared to the electoral influence of the party in those layers. The most encouraging result is probably that Syriza’s relative weight in the trade unions improved, approximately doubled, but it started from a very low level, which means that it is still the case that, overall, the strength of Syriza in the trade union movement and more specifically in the private sector remains inferior to the weight of the KKE.

Qualitatively, of course, things are a bit different because — and this is quite interesting — although the Communist Party overall remains even now a more organized and coherent force, its strongholds tend to be located in the less dynamic sectors of the trade union movement, or even in areas which haven’t been very active in terms of mobilizations recently, for various reasons (partly because there has been very little happening in the private sector.)

In the most dynamic unions, where mobilizations have been important, not only is Syriza stronger (that was actually already the case before), but it is in those places that it has developed the most. It is now, for instance, the leading force in the national union of teachers in secondary education, a key union in the Greek trade union movement. It is also significant that, in these sectors, the relative weight of the far left also increased, as did specific forms of trade union fronts, where you can see people coming both from Syriza and from Antarsya.

So there is a radical milieu that has developed in the trade union movement over this last period, and this is also the case in universities, where the radical left improved its position (even the KKE actually slightly improved its position), and the far left even more. While Syriza in universities stagnated — the turnout is quite significant in student elections in Greece, so it’s actually a relevant indicator — it is interesting that the milieu of radicalized left-wing students, which tends to vote for lists where Antarsya activists are actually the backbone, tends to vote more and more for Syriza outside the university in national political elections.

We have seen confirmation of this dual expression in other elections, specifically in the local elections, or in the gap between the regional elections and the European elections. In the regional elections, the lists presented by Antarsya, the far-left coalition, got about 2 percent nationally, and in the European elections, just one week later, it only got about 0.72 percent.

So it’s quite clear that for certain sectors very involved in mobilizations and social movements, at a local level or at the level of the union, they tend to support or regroup around initiatives or structures in which far-left activists are led. But, when it comes to political representation, then Syriza acts in a way as the key political representation for this overall constellation of forces.

The result is that one of the most significant evolutions of the last period has been the fact that the remaining divide within the Greek radical left now is between a very entrenched, and very sectarian, and very isolated KKE and all the rest (Syriza, Antarsya, etc.).

Could you tell us a bit more about the development of the Left Platform, since 2012: its components, its growth, its degree of coherence, and so on?

The Left Platform has two components, the Left Current, which is a kind of traditional communist current — essentially constituted by trade unionists and controlling most of the trade union sector of Syriza. These people in their vast majority come from the KKE, so they are those who broke with the KKE in the last split of the party in 1991. And then there is the Trotskyist component (DEA and KOKKOINO, recently fused).

The Left Platform has been put under intense pressure by the leadership but also by the way the functioning and the structure of the party has developed during and after the process of unification. This pressure from the majority of the party is combined with more structural reasons, due to the evolution of the form of the party, and the decline of movements and mobilizations over the last period in Greece.

All of these factors had a negative influence, or could have had a negative influence, on the relative weight of the Left Platform. But overall, the Left Platform resisted these pressures quite well. Its relative diversity acted as a strength. In this respect, we could say that despite the fact that the Left Platform is constituted by two different political cultures, its internal cohesion is much stronger than that of the majority bloc of the party, which is a much more heterogeneous regroupment of political cultures.

In the majority, you can find for instance people coming from mainstream social democracy as well as activists who feel close to the far left, movementist people oriented towards the so-called new social movements together, and very traditional reformist figures coming either from a Eurocommunist or from a KKE background, but also left nationalists, usually coming from Pasok, and the most extreme form of anti-nationalists — almost a Greek version of an anti-Deutsch phenomenon.

Not to speak of the Maoists (KOE)!

The Maoists are of course closer to that first left-nationalist pole, let’s say. So overall the level of heterogeneity is much higher on the side of the majority.

I think that what the Left Platform succeeded in doing in the period between the 2012 elections and the founding congress is that it attracted a broader layer of activists who do not identify with either the Left Current or with the Trotskyists, and who don’t really care about these distinctions.

What they do care about is supporting an internal left opposition or left perspective, a more clear-cut radical perspective within Syriza, and this is why the very manipulative tactics of the majority during the founding congress triggered a backlash and ended up strengthening the weight of the Left Platform, even during the very days of the congress.

We ended up by getting more than 30 percent of the delegates, even when you take into account that we were under-represented in the body of the delegates compared to the votes we got within the party. And to this one can add the 1.5 percent of the votes of the so-called Communist Platform (formed by the followers of Alan Woods and the International Marxist Tendency).

The evolution since the founding congress has been positive not only for the Left Platform, but more generally for the internal balance of forces within Syriza, because the majority of the party fissured during the period of the last regional/local and European elections. To be more precise, the left part of the majority — composed mostly of the movementists and a left split away from Tsipras’s current in Synaspismos (Left Unity) — has demarcated itself from the rest. (In typically Greek style, the result of this process is that we now have Left Left Unity (sic) and Right Left Unity (sic) around Tsipras).

The left of the majority has coalesced around the “Platform of the Fifty-Three,” signed by fifty-three members of the central committee and some MPs in June 2014, immediately after the European elections. They strongly criticized Tsipras’s attempts to attract establishment politicians, and for leading a campaign that didn’t give a big enough role to social mobilizations and movements, for developing a campaign style that was very centered on him as a person and structured around PR techniques and tricks, and also for softening some crucial edges of the program — more specifically on issues such as the debt, the nationalization of the banks, and so on.

So if the Left Platform got over 30 percent of the founding congress (plus the 1.5 percent of the Woodsites), has there been any way to measure since then what influence the Left Platform has within the party? And what would you estimate to be the size of the Left Left Unity people?

Well, my sense is that — and this is reflected at least at the level of central committee — the Left Platform plus the left wings of the majority bloc are actually the majority inside the party, and we have seen that in the last period, for example on the crucial issue of alliances. The leadership pushed very much for an alliance with Dimar, and it didn’t succeed. It didn’t succeed because the reaction inside the party was overwhelming, and the motor of that reaction were these two left components.

So despite the fact that the question of the euro still works to prevent a more cohesive attitude in what we can now call the broad left of the party, it is nevertheless the case that the room for maneuver for the leadership has become much more limited.

Unfortunately, the majority of the leadership has autonomized itself yet further from the party and disregarded the party decisions. I’m not here talking about some kind of simple divide between the base and the leadership — I mean autonomous from the party as a whole. And that is, of course, a very serious risk for the future.

The central committee has been convened very infrequently, and it is more and more the case that crucial decisions are made in a very opaque way, as a product of constant bargaining between various groups and lobbies trying to impose their views, and so on.

And how solid would you estimate the Left Platform is? I mean, they know what they’re against — the majority — but to what extent are they united and what are they for, especially in a context where governmental power is in prospect and thus there are potentially on offer jobs, governmental positions, and so on?

Well I think that as I said before, the level of cohesion, not only negatively, but also positively, of the Left Platform, is by far superior to that of the party majority. And even in terms of its programmatic intervention, it is much more cohesive and coherent. The role here of Costas Lapavitsas and his intervention on the economic front has been quite crucial, giving specific expertise on a whole number of economic issues.

What is very characteristic of the majority is that their views are not at all more coherent. Some people, to give a specific example, adopt a very firm attitude on the issue of the debt. They are positive that defaulting should absolutely be an option and that we should stand very firm on the demand of writing off the major part of the debt.

But when one asks, “Okay, and what will we do if we default?” and how viable is such an option without exiting the Euro — an almost immediate consequence, and not a matter of choice — they tend to refuse to give an answer and bypass the issue by saying that it will depend on the overall balance of forces in Europe. The Left Platform, in contrast, has much more precise answers.

In contrast, DEA has a more internationalist — or what it thinks as being a more internationalist — type of culture. This means that, on issues such as Cyprus or relations with Turkey, or on Ukraine or things of that kind, there are differences, with qualifications, depending on the specific issue.

What about how the Left Platform faces the question of the potential victory of Syriza? Is there a common line about not being part of the government, not taking on ministries, or about what kind of mobilizations — extra-parliamentary or social mobilizations — they could engage in?

I think that what defines not only the Left Platform but the broad left within Syriza, which includes a substantial part of the majority bloc, is the fact that it sees the whole prospect of accessing governmental power as a means of triggering social mobilization. And it really means it, because it is immersed in a type of practice which is oriented towards mobilization.

The very conception it has of the party and what the political process is about is oriented toward activism, to put it briefly. It’s quite clear that the type of political approach which has been put forward by Tsipras or the majority of the leadership during this last period tended to give a much more limited role to social movements and mobilizations.

Just to give you an example, in 2012, Tsipras very strongly emphasized at that time that the perspective was not just a Syriza government, but a government of the whole of the anti-austerity left — which is still the case, but doesn’t mean much now, because it’s clear that neither the far left nor the KKE will ever accept this type of collaboration.

But also — and at least as importantly — it was to be the government of the anti-austerity left and of the social movements. At that time, Tsipras referred specifically to the experience of Bolivia, and one of the most significant initiatives taken by Syriza, between the May and June 2012 elections, was to call a kind of general assembly of the movements in a dialogue with the leadership of Syriza. It was an absolutely extraordinary event.

The participation of leaders of campaigns, of trade unions, of things of that type in a dialogue with Tsipras and some other members of the leadership gave a very strong image of the type of political and social perspective that Syriza at the time was defending. There has been nothing comparable to that in the last period.

On the other hand, we should also say that the whole atmosphere in Greece has changed dramatically since: there has been a decline in social movements, combined with an atmosphere of relative demoralization and passivity — despite, of course, important sectoral struggles.

With qualifications of course, the overall atmosphere in the country is very different than in 2012, marked especially by the decline of social mobilization, so the line of Syriza from that perspective is more one of an adaptation to the dominant trend.

So the model for the Left Platform would be something like the Popular Front in France, where left government is the leverage to mobilize class struggles and social movements outside, and who then put pressure on the government? So one foot in, one foot out?

Well, it’s difficult to predict. You refer to the Popular Front government, but the Popular Front situation was one where the demands of the social movement were completely different from the very limited program of the Popular Front itself. So, the victories, the conquests, the successes of the Popular Front immediately came from the pressure of the mass movement.

In the case of Syriza now, I think that it would be more adequate to see the victory of Syriza acting itself as a trigger, because it gives confidence and it breaks with the atmosphere of resignation of the last period, but also because it will takes measures to open up a space for social mobilization. Regarding the latter, I think that the most crucial question is probably the proposal to put the minimum wage back to its pre-memorandum level and, perhaps even more importantly, to re-establish the whole system of collective contracts and labor legislation, which has been completely slashed over the last four years.

That would liberate a space not only for struggles, but also for rebuilding the trade union movement, which is in a terrible state in Greece now.

But on the question of ministries and playing a role in the government, there’s no common line? People will decide when the time comes?

No. Absolutely not. I think the Left Platform is very clear on the fact that its level of involvement at the purely governmental level depends on the type of line that will prevail in the strategic choices of that very government. This is the way it approaches the whole issue, and not the other way around.

And this is perhaps the indicator, I think, of the differences that we have with the political practice of others: we do not put the issue of ministries first, we put the issue of the line taken, and of the key immediate strategic decisions which will be taken by the government. So everything depends on what line will prevail. And, at the moment we are speaking, not everything is clear, you know? To put it very gently: there are many things that need to be clarified within Syriza’s program.

But, overall, our line is the following: we should stick to the absolute fundamental commitments of Syriza as they are.

The present program or the 2012 program?

I mean the present program. Even the minimal platform presented at the Thessaloniki congress and slightly updated by Tsipras recently: even sticking to that means going to a major confrontation, which means of course being supported by and stimulating popular mobilization on the one hand, and mobilizing the party and other social and political subjects in the whole process.

This is the role, I think, of the Left Platform: to play, to be a catalyst in this kind of dialectic between what will happen at the level of government and what will happen at the level of society. And this is the mission, perhaps the historical mission, if things go well, of the Left Platform. We have a more coherent force within the party that can act as a catalyst of energies and prevent a gap from opening up between what’s going on at the level of grassroots mobilization and at the level of government.

As you know perfectly well, the classic maneuver would be to offer the ministry of labor and the ministry of sports and culture to the left and keep more of the key ministries for the right wing of the party . . .

Yes. But this is not the risk now, actually. I think the risk now is that they will precisely not do this. They will offer some strategic ministries, but without perhaps being clear on the political line. Which means that they will tie our hands in advance.

So I think the crucial thing is whether the line of taking responsibility for a confrontational approach, both internal, and of course, with the EU and European forces, prevails. If we go in that direction, that battle cannot be won without very serious clarifications within Syriza and within the Greek left, more broadly.

My hope (but I think it is a realistic one) is that such a perspective will also provoke realignments beyond Syriza, generally, and that sectors that remain now skeptical, hesitant about Syriza, in that type of conjuncture, would take a more decisive stance. Then I think we would have something like a united front.

Can you talk a bit about Panagiotis Lafazanis as the key spokesperson of the Left Platform?

Yes, he really is the key figure, and this is a strength and also a weakness. Syriza is such a leader-centered party, or tends to be such a leader-centered party, and I’m afraid that the Left Platform, and more specifically, the Left Current, which is its biggest component, is very much a person-centered organization. Of course Antonis Davanellos (of DEA) is also quite prominent, but at the level of national politics, Lafazanis plays a very crucial role.

Lafazanis is representative of that generation of activists who have come to the forefront during the struggle against the dictatorship. He’s one of the very rare cadres of the Communist youth — fewer than ten throughout Greece — to escape from arrest during the entire period of the dictatorship. So he’s of that generation.

He climbed the hierarchy of the KKE in the 1970s and 1980s, and he became a member of the politburo of the party, but he was more particularly close to the former and historical secretary general of the KKE from 1973–1989, Harilaos Florakis. He left the party with a whole number of leading figures in the 1991 split, of which he was a central figure.

But the specificity of Lafazanis is that, where the others drifted to the right, broadly speaking, and many of them actually left Synaspismos or Syriza, or stayed but moved towards much more rightist positions (such as Dragasakis), Lafazanis stayed staunchly Marxist and very coherent, but breaking decisively with Stalinism (although we have to say that he was one of the people who, behind the closed gates of the KKE leadership, were already very critical of the Soviet Union during the late 1970s and 1980s.)

Lafazanis is now identified and targeted by the Greek media because he’s seen as the hardliner. He is the figure of Syriza that the media and of course the Right and the pro-system forces love to hate, and constantly stigmatize. He is presented as the Mr Anti-Euro and the Mr Break-with-the-EU of Syriza. Just to give you a very recent example, immediately after the breakdown of negotiations between Syriza and Dimar, the main daily paper in Greece (Ta Nea) ran an vociferous editorial on the first page, unsigned, saying “Greeks, beware: You vote for Tsipras, but actually it is Lafazanis who rules the party.”

One has to understand that one of the main reasons why the media and the political elite and the dominant class are hostile to Syriza is that, within Syriza, there are very strong left currents. Tsipras has to take that into account, and this is why there are front-page headlines saying “Tsipras! Do a Papandreou!” namely get rid of internal opposition and be a real leader. Get rid of these loony leftists and hardliners and so on.

Since we mentioned the KKE, we might as well deal with that quickly. People are still curious about it. To what extent do you think its line has some kind of rationality, or is it just suicidal?

Both. I think that the KKE’s only preoccupation is actually to keep the party ticking, to keep the party afloat. It’s clear that the KKE’s dream would be to go back to the 2009 situation, when it was still the dominant force of the radical left. This is what the KKE really wants. It wants to be a party of 7–8 percent of the electorate, managing certain sectors, etc.

It is a very conservative type of apparatus, and this creates a big gap between the KKE’s internal nature and the type of Third Periodrhetoric, which at the surface is what the KKE is spouting. At the level of discourse, you have constant references to revolutionary rhetoric, to socialism, to the working class, workers’ power, and so on, but actually, the KKE has remained extremely passive all these years.

It was consistently very hostile to grassroots mobilizations. It condemned in an absolutely crazy way the movement of the squares (in spring 2011), describing it as part of an anticommunist plot. So it’s a very conservative party, a party that doesn’t like fundamental changes.

But is this an organic worldview? Isn’t it imposed by authoritarian forces in the leadership?

It is imposed, but they have a very strong apparatus, and they have built a very cohesive party. They have ruthlessly eliminated all oppositions over all these years and have succeeded in keeping control of the party. I suspect that the very poor results it will achieve in the forthcoming elections will probably have an impact.

At the last KKE congress, in April 2013, we saw that there were serious internal disagreements, but the leadership succeeded in getting rid of most of the dissidents, and I think everything will depend on how the situation will develop. The whole worldview of the KKE and part of the far left is to bet on the failure and the betrayal of Syriza. They are calling for it, and there is a dimension of a self-fulfilling prophecy in this.

This perspective has played a role, and we have to take it into account — and I’m not saying that to excuse the leadership of Syriza from its responsibilities. The fact that these forces did everything they could to isolate Syriza from any other force within the radical left certainly facilitated attempts to moderate the line and the approach of the party.

The wager is precisely this imminent failure of Syriza will lead to the radicalization of the masses and liberate them from their reformist illusions, but this is something that is categorically rejected by growing sectors of Greek society, who see it for what it is, namely a completely irresponsible and pretty mad line. The result is a waste of forces, which might only change if the situation warms up over the forthcoming period.

For the first time in Europe since the aftermath of World War II, a party of the radical left has beaten the social democrats at the polls. Syriza overtook Pasok thanks to its own breakthrough but also due to the collapse of the social democratic vote. Do you think that its predominance can last?

The shock therapy that has been applied in Greece has had the same political results as in the other countries of the global South where it has been previously implemented. The old political system has collapsed, and this is the first time it is happening in a western European country in the postwar era.

The two main parties have been struck by this: Pasok, yes, but also, if to a lesser degree, New Democracy. In 2012, it lost 20 percent of its support, receiving the weakest vote the Right has ever had in all the time that Greece has been an independent state.

Pasok’s qualitative collapse is even more serious than what the numbers at the national level would suggest. In the main urban centers, Pasok came in sixth or seventh place. In most of the working-class districts that used to be its strongholds, it was beaten by the neo-Nazis of Golden Dawn. Its score among eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds stood at just 2.6 percent, and most of its electorate (obtaining a total of 13.4 percent of the vote) was made up of pensioners and the inhabitants of rural areas and small provincial towns.

So we could say that in Greeks’ eyes Pasok has been totally discredited.

Today there is no relation between Syriza and Pasok . . .

Outside Greece it is hard to imagine the gulf separating Pasok not only from the radical left but also from Greek society itself. Since the 1990s, for the KKE, and since the mid-2000s for Syriza, there is no possible or desirable alliance between Pasok and the radical left, at any level.

So the reason why there’s a cordon sanitaire around Pasok is that the rest of the Greek left no longer consider it a party of the Left.

You need to understand one thing about the language of the Greek left. Up till 1974 there was no socialist party in Greece, and in our political lexicon to say “I’m on the Left” means “I am to the left of Pasok.” Indeed, Pasok has never been considered a party of the Left in the Greek sense of the word. In Greece, the Left is connected to the communist tradition, in the broad sense of the term. And that excludes social democrats like Pasok.

Let’s talk about the re-centering of the last year of the line of Syriza. What has been going on?

Essentially, what we are talking about in the so-called re-centering of the party is the fact that the discourse of the party became a kind of double- or triple-level discourse. Tsipras or the leadership of the party have developed many levels of discourse.

The two main economists of the party — and they are the real representatives of the most rightist tendencies within Syriza, Giannis Dragasakis and George Stathakis, in a much more straightforward way for Stathakis, in a much more tactically maneuvering kind of way for Dragasakis — developed their own distinctive approaches to the economic issues, which were systematically different from the decisions of party congresses or the official position of the party.

Often, Tsipras has had to intervene to re-establish some kind of balance, but this process meant that the initial position — the position of the 2013 congress — was softened up. Dragasakis and Stathakis, for example, made statements that a Syriza government would never move unilaterally on the position of the debt, but the decision of the party congress explicitly says that all weapons are on the table and that nothing can be ruled out, if a Syriza government is blackmailed by the creditors.

The two of them have been unclear at times, depending on the interlocutor or the audience they had in front of them, even about the issue of canceling the memorandums or whether Syriza was demanding a write-off of all or just part of the debt.

Secondly, Tsipras has been traveling a lot over the last period. It was necessary, because he is the leader of a party which until recently had about 5 percent of the vote, and he lacked any credibility as a head of a state. He needed to improve his credibility not to speak of his knowledge of the international scene.

So he went to places or institutions that are patronized by the mainstream or even the economic oligarchy, like the Ambrosetti Forum. These are kinds of very exclusive clubs in which very important people of business and of finance convene and discuss. The impression was that when he was there, he was presenting a much milder version of the approach of the party.

So for instance, when he went to New York and spoke at the Brookings Institute, he made repeated references to the New Deal and Franklin Roosevelt. When he went to Austin, TX he said that Syriza would never abandon the euro, whereas the position of the party — and also what he himself also said later — was that we do not want to stay unconditionally in the euro, without qualifications and so on.

All this created the impression that on the very crucial, strategic issues Syriza is not completely clear, and that it has different levels of discourse, thus provoking skepticism about the real intentions of Syriza and how determined it is to resist the pressure which every sensible person is aware a Syriza government will have to face.

This has constantly triggered cycles of internal debates and arguments within the party — which has been painful at times, but nevertheless delivered some results. I think it was necessary, but it was, as I said, quite painful at times. In the end, there has been a cost, but at least Syriza didn’t publicly renege on its fundamental commitments.

And we see that now, actually. Although there is a lack of clarity concerning the means to achieve those commitments, it has become clear to everyone that what Syriza is putting forward has very little to do with any agenda of any European social democratic party today. It is an agenda of really breaking with neoliberalism and austerity. Syriza appears as bringing a type of political culture that is linked to a social, political, and even ideological radicalism still very much inscribed in the DNA of the party.

So there has been some fallout from this process in the last period? John Milios is known in the Anglophone world for his books and now for his interview in the Guardian and seems to have taken his distance from the leadership?

Until recently, Milios didn’t have a very specific strategic position within the main economic team, (Dragasakis and Stathakis have been leading the game). His role was to provide a kind of Marxist argumentation against those who were advocating a break, or a clear break, with the EU, and more specifically, on the issue of the euro.

Milios provided a lot of Marxist and radical types of arguments, saying that breaking with euro means the devaluation of labor, a regression to nationalist positions. He more or less accused — in a manner that he has carved out for himself theoretically over decades — people who put forward such themes of breaking with the euro of recycling the old “developmentist” center versus periphery type of approach of the 1970s, and of having as their real political project the development of a nation-centered Greek capitalism.

On this view, presumably, avoiding the break with the euro at any cost acted as almost a mythical guarantee for an internationalist and socialist perspective. What that meant, in terms of concrete choices, was that Milios defended the mildly reformist positions of Dragasakis and Stathakis.

Milios started taking distance from that at two levels. First on the issue of political alliances, where it was clear that, with qualifications, he doesn’t want openings to people coming from Pasok or old establishment elements. He also rejects softening of the anti-neoliberal edges of the program, and I think he was very disappointed by the fact that Syriza in the end doesn’t have a very specific elaboration on the subject of fiscal reform (which was one of his main themes), i.e. audacious redistributive policies — taxing the rich, and so on.

It is quite unclear what Syriza will do with the banks, and what it will do about privatizations. It will certainly cancel at least some of the more scandalous cases of selloffs of public assets at completely ridiculous prices. But the recent statements by Dragasakis and Stathakis about banks and privatization are not very encouraging, clearly retreating from the decisions and commitments of the congress.

So these are very important issues that a Syriza government will have to face, not even in long- or mid-term, but immediately.

Maybe you can say something about the series of candidates that have been appointed by the majority before the forthcoming election?

I think this is once again a very real issue in the party. At the level of the party branches, and also at the level of regions, nearly all the attempts of people from this old political elite — either locally or nationally — to infiltrate, to get posts or positions, failed. They were rejected by overwhelming majorities, and this is also an indicator of the fact that the Left Platform and the “broad left” of the party are not isolated sectors but are really capable of imposing their views on very crucial issues.

The reaction of Tsipras and the leadership was first to systematically delay the sessions of the central committee, thus paralyzing this level of decision making. Thereby, the leadership obtained something like a carte blanche for 50 out of those 450 overall candidates (there are 300 MPs, but 450 candidates) — which means that it’s only right now that we know the final composition of all the lists.

The idea of a collaboration with Dimar failed because of the reaction it encountered. Many candidates at the local level were also rejected by the local federations and branches. And now there is a kind of dispute about the people who will be parachuted, in a very top-down way.

On the other hand, the fact that Costas Lapavitsas has been accepted as a candidate is a major development. There was already a discussion about this during the European election, and in the end his candidacy was rejected by the majority of the party leadership.

This is very important because Lapavitsas is not just an individual — he really is the symbol of a very specific and very determined approach to the whole issue of how to deal with the crisis, with Europe, with the debt, with the whole set of economic issues. And having him on the list and as an MP makes it much more credible that when Syriza says “really, all options are on the table” — it really means it.

If Syriza wins first place in the parliamentary elections, it will need to form a parliamentary majority. Is this possible — and how?

I wouldn’t rule out a Syriza landslide. The polls have it at 35 percent, so not far from an absolute majority, since the Greek electoral system gives a fifty-seat bonus to the leading party. So it is possible and even probable that Syriza will have an absolute majority.

It is true that it does not have any obvious allies: the KKE has ruled out any alliance, while Dimar, which was part of the ruling coalition a year ago, has been wiped out. So that is one of the difficulties it faces, but we shouldn’t forget that this in its own way expresses a crucial political question: after all, some people want to moderate Syriza’s positions, relying on the concessions it is going to have to make in order to build alliances.

The Greek electorate is aware of this, and it could very well give Syriza a clear majority so it can carry out its program without having to make concessions in order to enjoy a parliamentary majority.

What do you think of New Democracy’s attitude, playing a lot on the “red scare” and the fear of chaos if Syriza wins?

It should be understood that after four years of memorandums not only the Right but also the center-left — or what’s left of it — are extremely authoritarian formations, the partisans of an iron fist policy.

The current prime minister, New Democracy’s Antonis Samaras, comes from the nationalist wing of that party, and he is surrounded by an entourage most of whom came from the extreme right. This is a diehard right wing that plays on the deeply anticommunist reflexes of part of the Greek population.

So the government uses a rhetoric of fear: they have no other arguments. And that is part of their authoritarian, “muscular” vision of politics. If Syriza fails then the prospects for the country will be very reactionary and authoritarian.

What are Syriza’s priorities for Greece?

There are four main things to work on — and here I’m not putting them in any particular order. The first consists of emergency measures to deal with the most shocking aspects of the disaster of recent years: reconnecting the electricity supply to all homes, school meals for all kids, and reestablishing a health care service worthy of the name — as things stand, a third of the population is excluded from the health care system.

The second thing: dismantling the hard core of the memorandums. That would mean setting the minimum wage back where it was before 2010, as well as the collective bargaining agreements and social legislation that have been entirely destroyed. That would open up a field of action for labor, and would result in immediate improvements. We also have to get rid of the absurd property taxes that the state has been extorting from the population for several years. All this is non-negotiable.

The third thing to work on is the debt — and here there will be some negotiation. There is no chance of sorting out Greece so long as servicing the debt under the memorandum régime continues to grind the country through the mill.

There has been a bloodbath of public and social spending cuts in order to free up budget surpluses to pay off the debt and end the need to finance it. This is impracticable. The budget surpluses could never be enough to cover the costs of servicing the debt, whose burden has increased as the GDP has fallen — it’s now reached 177 percent of GDP.

We need to find a solution to this. Syriza will insist on a solution like the one that was demanded in the case of Germany in 1953: that is, canceling the greater part of the debt and paying back the rest within the terms of a growth clause.

But what will we do if the Europeans refuse? Once again all the options are on the table, but Syriza will not retreat and let itself be blackmailed the way Anastassiades, the rightwing Cypriot president was in spring 2013 when the parliament of his country reject by a unanimous vote the bailout plan proposed by the EU.

The fourth thing to work on is kickstarting the economy, which has been destroyed, in order to deal with the massive unemployment (26 percent, and 50 percent among youth) that Greece is currently experiencing. Only public investment can really get to grips with this. It’s a very complicated question, but we need to relaunch the economy in a way that suits social and environmental needs, much unlike what we have currently.

So let’s imagine that the elections have happened and that Syriza has obtained an overall majority without having to rely on an unreliable ally. A landslide victory. As you know, Paul Mason wrote a piece about what the dangers would be for Syriza in the first few weeks after such an event, and the kinds of enormous pressure it would come under, both from markets and from the EU.

First, it is not appreciated how violent the overall political climate and the electoral campaigns are in Greece. And this was the case in 2012. Honestly, it’s much closer to an electoral campaign in a Latin American country than a European country.

The whole approach, and types of rhetoric and discourse, developed both by the current government and the media are to paint Syriza as a fundamentally illegitimate force. This is the deeper meaning: to say that, when Syriza comes to power, it will be a totally apocalyptic scenario — that Greece will be expelled from the eurozone, the shelves of the supermarkets will be empty. They are even making photomontages with empty, or supposedly empty, shelves in Venezuela or Argentina, with the message, “This is what will happen in Greece.”

On the other hand, Syriza wants to reassure the electorate that there are people and forces in Europe that are more open to negotiation and to some forms of concession. Tsipras for example wrote a very unfortunate article suggesting that the Italian and the French governments were taking some distance vis-à-vis austerity politics.

Now they are highlighting statements made by the German Social Democrats or an article in Bloomberg, claiming that there is no possibility of “Grexit” — this is not a feasible scenario, that no one is considering it. But the crux of the matter is that it is the case that the way Syriza is presented by dominant European media has changed in the very last weeks or days.

What is the meaning of this change? Before, the line was, “These are hard leftists, and they are a threat, and we should counter them and smash them and so forth.” Outright hostility. Now, the tone is, “Actually, they are more reasonable than they seem, and, in any case, not much will change.”

So, the bottom line is that, whatever you do, you will have to remain within the existing framework, and some people are playing the good cop version of this and others are playing the bad cop version. But, the reality is that the iron cage is still there and the room to move you will have is actually nonexistent.

I think that the moderate position within the party is understandable up to a certain point — as some kind of a more defensive discourse might be perhaps necessary in certain circumstances — but the problem is that it doesn’t prepare the people in society for what will inevitably come in the case of a victory for Syriza, namely that decisions to implement completely its program will turn out to be very confrontational, both internally and with the rest of the European Union.

Once again, I think that even during the campaign the left of Syriza has a role to play by, in a very loyal way, remaining faithful to the program and so on, but emphasizing the fact that things will not be easy, that we should be prepared for a serious battle, and we have to emphasize this depending on the moments and the types of weaknesses of the majority positions.

But Tsipras is also playing that card sometimes, so there is a constant game to balance these various contradictions. If you consider things from a certain distance, the contradictions lie within the situation itself in the sense that it would have been difficult not to have these type of contradictions within the existing situation.

We are talking about a situation where the level of social mobilization has been very low for a quite significant period, and the context is an electoral context, not an insurrectional one. The balance of forces internationally is at Syriza’s disadvantage, despite the recent developments in Spain. Overall, in Europe, it’s quite clear that a Syriza government will be quite isolated.

Therefore, these hesitations, ambiguities, and oscillations, are partly inevitable, provided that we are lucid about the fact that what is ahead of us is a choice between going ahead towards confrontation or giving up and surrendering. I think there are no intermediate options between surrender and confrontation.

Let’s tackle the question of the debt and the euro, which are the main cleavages and essential questions on the radical left. They are, in part, taken up both by the Left Platform within Syriza, and by Antarsya.

They are key questions that they claim the majority doesn’t address adequately, avoids, or tries to fudge. Can you say something about both the symbolic importance and more concretely, the strategic importance, in light of a possible victory for Syriza?

There are many questions in one here. Let’s start with the symbolic level: I think that, in terms of ideological hegemony, there is no doubt that the ideological hegemony of the dominant class in Greece has been based on the European project — the idea that, by joining the process of European integration, Greece would become a “modern” country, a “developed Western European” country, and would definitely and irreversibly move into the club of the most developed and advanced Western European society.

So that’s a kind of longue durée fantasy, I think, of the Greek nation since independence, to become a fully accepted part of the Western European world, as it were. And it seemed, in the first decade after joining the Euro, that this fantasy had become a reality.

Of course, one shouldn’t underestimate the symbolic strength of the euro: we can think here of Marx’s analysis of the role of money and currency, and all the symbolic value attached to that. And it worked. Everyone knows that, before the crisis, before the memorandums, Greece — as well as the other countries of the European periphery — had the highest levels of approval, both for the European project and for the common currency.

I think this is a typical mentality of a subaltern country. Of course these levels of support have dramatically declined during the crisis, however the reality is actually much more ambivalent than this: on the one hand, there is distrust of the EU, because they imposed the memorandums and the troika rule.

On the other side, it seems that in a state of despair, the people cling to the last remnants of their former symbolic status. So they’re even more desperate sometimes about losing their status or their supposed status as full members of the “club” of the most advanced European countries. Things are thus quite complex on the level of common sense.

Now, concerning political strategies: the currents within Syriza, and more particularly the currents coming from a certain Eurocommunist background (and, to a lesser extent, the currents coming from a more movementist background), display a strong sense of support of the European project as such.

On the contrary, the currents coming from the left of the KKE (which is the case of the Left Current, essentially) are traditionally much more hostile to European integration and have maintained from the outset of the crisis a much more negative attitude vis-à-vis the euro and the whole strategy, and the EU as an institution or as a set of institutions.

But not from a left nationalist perspective?

I think it’s a mistake to say that the currents coming from the KKE are left nationalist currents. There is a tradition of left-wing patriotism, which is linked heavily to the antifascist sequence, let’s say. But if you take, for instance, the conflict with Macedonia, or even the relations with Turkey, the KKE and the people coming from the KKE matrix, had extremely mild positions on Turkey, or in the case of Macedonia, the KKE was the only party not to be part of the so-called national consensus in the early nineties, against national recognition of Macedonia.

Within Syriza, the forces of the Left Platform developed a principled critique of the EU as such and sees Greece being part of the eurozone as one of the key dimension of the problem. If you are not ready to break with the eurozone, if that turns out as the only option left in the case of a Cypriot-type blackmail, then your hands are tied in advance.

The majority of Syriza strongly objected to that approach and put forward arguments which superficially seem very leftist, saying that such an approach leads to a withdrawal back into national solutions. They criticize not only a lack of internationalism but a even lack of anticapitalism, because the project underlying this is, they claim, a return to nationalist capitalism. And this was very much in line with what the rest of the European radical left was saying.

Under the influence of Antonio Negri, or those kinds of positions?

Concerning the majority of Syriza, I think that it’s not Negri. Negri might have played the role concerning the more movementist components, but concerning the majority of Syriza, I think the key role is played by Die Linke and the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. They play a role in the diffusion of a number of themes such as an agenda for an internal reform of the EU, an understanding of the crisis, and of the way to get out of it as essentially an issue of redistribution.

And behind this is the idea that we have to change the balance of forces directly at the level of the EU, avoiding any kind of unilateral move at the national level. Any other strategy is said to amount to a regression because it demonstrates nostalgia for the old nation state and so on. So these were the term of the debate. The question of the euro became a point of cleavage.

The other issue, which is at least as important, is the issue of the debt. Here, the geometry or the terms of the debate are not the same. Some of the people who are not in favor of breaking with the euro are in favor of a radical attitude on the debt. They seriously consider defaulting on the debt as something that might be unavoidable or at least needs to be considered as a weapon in the negotiation around the restructuring of the Greek debt.

The approach of the majority of Syriza still is that you can distinguish the two issues and start the process around the discussion of the debt. According to this logic, because breaking with austerity and the memorandums is non-negotiable, you are in a position of reverse blackmail, the weak against the strong. You break with austerity unilaterally, and therefore Merkel et al have no other choice than to accept a positive restructuring of the debt in favor of the debtor country.

I think that these terms of the debate themselves are somehow circular. The real issue is the following: everyone agrees that breaking with austerity and acting unilaterally on the issue of the memorandum is the only way out of the current situation. And, on that issue, we can have the majority support of Greek society, so this is a decisive aspect of the terrain.

Then the question is whether this can happen within the framework of the eurozone or not? This is, I think, a still open question, and only practice will provide an effective answer.

My opinion, and that of the Left Platform, is that these issues cannot be resolved without dealing with this question. The issues of the debt and the memorandums are the litmus tests of the approach of the majority of Syriza.

Neither drachma nor euro, but the ruble and international socialism!

Well, you can take the ruble out of the equation now, but yes some kind of mythical workers’ power. This is turned into an immediate line of demarcation between reformists and revolutionaries, thereby completely underestimating (a) the balance of forces within Greek society, and the position of the radical left properly speaking, and (b) confusing a more strategic goal with transitional objectives and demands.

And this ultimatism, which puts this question forward as a prerequisite for any kind of radical or common or joint political approach, has been decisively rejected in the present conjuncture. The test of reality will come very soon. We’ll know whether it is possible to break with austerity and remain within the eurozone. Everything so far suggests that this is not possible.

This is the message of both the type of blackmail Ireland and Cyprus have been subjected to in the recent past, and of the current approach of the European governments who now say, “Okay, perhaps Grexit is avoidable provided that you stay within the current framework. Perhaps you’re not as dangerous and threatening as you appear or pretend to be, therefore you will very quickly follow the path other left-wing governments have followed in the recent past, in various European countries, starting with France.”

So I think that the Left Platform will be vindicated by what is coming and what is ahead of us, but the right way to approach the issue is not to address the euro as a prerequisite but also to decisively reject the idea that we should accept sacrifices or concessions in order to stay within the eurozone.

But doesn’t that in a sense reduce the difference between the majority and the Left Platform on this question to a false choice? The cleavage doesn’t seem to be so important, and much of it hangs on public declarations, which are partly performative: bluff, facing off, and calling Merkel and company’s bluff. It doesn’t seem very substantive.

I think it’s far more substantive than what you suggest it seems. On paper, you can have a text that reflects this kind of compromise: “we will not accept sacrifices for the euro,” “all options are on the table, but our choice is not exiting the euro as such,” and this is indeed the type of formulations you find in all the key party documents. But this compromise is very unstable, and what has happened has eventually revealed this.

There is thus a position, on the one hand, that “we should stick to the euro,” and, on the other, “we should prepare ourselves for all kinds of initiatives and objectives.” The concrete outcome is that Syriza is unprepared. There is no plan B. There has been no political preparation of the party, of Greek society, of the people. And this fact is still used as a way to blackmail the Greek population and will undoubtedly be used in the future to blackmail a Syriza-led government.

Just to be clear: we are talking about exit, or potential exit, from the eurozone, not from the European Union? Nobody’s proposing exit from the EU in Syriza?

Not completely true. At the very least, the Left Current is hostile to the EU as such.

But one could imagine Greece nevertheless remaining a non-eurozone member of the EU?

Well, yes, but it also raises a whole issue about European treaties as such and the extent to which they are compatible with following any kind of alternative path. From that perspective, you might say that the position of the Left Front in France, at least on paper, regarding disobedience vis-à-vis the European treaties is relevant here. Except that, as we have seen in the recent elections, although this was in the program and on paper as a position, it has never been publicly supported and developed and defended.

The state of the debate is more advanced in Greece because these have become real stakes in a debate in broader society and not just in very narrow intellectual or activist circles. And I think there are precious lessons to be drawn from that for the broader European left.

How does NATO relate to all this?

I think that opposition to NATO is still very much part of the genetic code of the Greek radical left. However, since the start of the crisis, the opposition to the troika rule has superseded all the rest. It is even the case that the US with Obama is now perceived by many, even on the Left, as more benevolent than Merkel’s Germany.