Piketty: Tediously telling us the obvious. In a way the pinnacle of useless mainstream economic theory. Statistical economists are in a way the willful moles of a notoriously myopic profession.

“I am Not a Marxist”

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen the “Public” Broadcasting System Newshour’s Paul Solman sat down with the overnight academic rock-star Thomas Piketty at the height of the latter’s celebrity in the United States (US) last spring, Solman’s first question was about his politics:

Solman: “Capital, capitale, the name of Karl Marx’s famous work, so are you a French Marxist?”

Piketty: “Not at all. No. I am not a Marxist. I turned 18 when the Berlin Wall fell, and I traveled to Eastern Europe to see the fall of the communist dictatorship….I had never had any temptation for communism or, you know, Marxism.” [1]

The celebrated French economist Piketty may have invited comparisons with the great anti-capitalist Marx by writing a bestselling tome titled Capital in the 21st Century (NY: Belknap, 2014), using Marx-like (or Marx-mimicking) phrases like “the central contradiction of capitalism” and “the fundamental laws of capitalism,” and arguing that economic inequality is deeply rooted in the institutional sinews of the profit system. But in his surprise spring and summer US bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Belknap, 2014) Piketty tells us that Marx was wrong. While he admits that “Modern economic growth and the diffusion of knowledge… have not modified the deep structures of capital and inequality,” he argues that they “have made it possible to avoid the Marxist apocalypse.” (Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, p.1, emphasis added).

In the introduction to his magnum opus, Piketty says that he “belongs to a generation that came of age listening to news of the collapse of the [Soviet bloc] communist dictatorships,” something that “vaccinated [him] for life against the conventional but lazy rhetoric of anticapitalism….” He says he “ha[s] no interest in denouncing inequality or capitalism per se – especially since social inequalities are not in themselves a problem as long as they are justified, that is, ‘founded upon common utility,’ as article 1 of the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen proclaims.” (Piketty, 31, emphasis added)

Savage Inequalities Right Out of Capitalism

But what justifications of “common utility” can possibly be found in the extraordinary level of the socioeconomic disparity the profits system has brought into being today? Just here in the US, where 16 million children languish below the federal government’s inadequate poverty level, the top 1% owns more wealth than the bottom 90% and a probably comparable share of the nation’s “democratically elected” officials. Six Walmart heirs have more wealth between them than the bottom 40%. Between 1983 and 2010, the Economic Policy Institute has calculated, 74% of the gains in wealth in the U.S. went to the richest 5%, while the bottom 60% suffered a decline.

This savage inequality comes courtesy of the class-based socioeconomic regime called capitalism, a defining aspect of which is its constant underlying tendency towards the concentration of more wealth in fewer hands – a tendency Piketty demonstrates with more than two centuries of brilliantly compiled and analyzed data. It also comes from forms of elite business-class agency that Piketty does not come close to thoroughly examining. Last May, the left economist Jack Rasmus rightly took Piketty to task for missing two leading explanations for dramatically increased inequality in the US since the 1970s: “the manipulation of global financial assets and speculative financial trading” and the “reducing of labor costs across the board.” Focusing almost exclusively on changes in the tax system (the third leading explanation by Rasmus’ account), Piketty ignores both the remarkable proliferation and de-/non-regulation of financial instruments (credit default swaps and other complex derivatives and financial “innovations”) and the “top-down class war” (former UAW president Douglass Fraser) that corporations have waged on unions, wages, job benefits, and the social safety net over the last four decades. These are critical omissions.[2]

An Alternative System?

Does the misery and collapse of the Soviet Union/bloc really discredit Marxism or other forms of “anticapitalism”? “One can debate the meaning of the term ‘socialism,’” Noam Chomsky noted in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, “but if it means anything, it means control of production by the workers themselves, not owners and managers who rule them and control all decisions, whether in capitalist enterprises or an absolutist state.”[3]Bearing that consideration (true to Marx) in mind and adding in the question of who controls the economic surplus, the US Marxist economist Richard Wolff reasonably describes the Soviet experiment as a form of “state capitalism.” Under the Soviet model, “hired workers produced surpluses that were appropriated and distributed by…state officials who functioned as employers. Thus, Soviet industry was actually an example of state capitalism in its class structure.” By calling itself socialist – a description of “Marxist” Russia that US Cold Warriors and business propagandists eagerly embraced, for obvious reasons – the Soviet Union “prompted the redefinition of socialism to mean state capitalism.”[4]

In a mostly flattering review of Piketty’s book, the Brooklyn-based Marx fan and political-economic commentator Doug Henwood remarked that “the USSR…for all its problems, was living proof that an alternative [to capitalism] economic system was possible.”[5] Alternative post-capitalist systems are indeed achievable, but Henwood’s statement on Soviet Russia is dubious in light of the Soviet Union’s class structure and demise.

The nature and collapse of the Soviet system might with reason be seen as discrediting the “lazy anti-capitalism” of say, the old (Stalinist) French Communist Party. But, as Henwood wrote in his Piketty review, and here we must concur, “Anticapitalist rhetoric need not be lazy.” Marx’s certainly wasn’t. Neither is that of numerous subsequent radical thinkers and activists like, say, Chomsky or Wolff. (Or Sweezy or Baran, Huberman and dozens of others.—Eds)

“Dark Prophecy”?

What is “the Marxist apocalypse” that we have “avoided” in Piketty’s view? Piketty means the growing division of Western industrial society between a wealthy bourgeoisie on one hand and a vast ever more miserable property-less proletariat, leading to working class socialist/communist revolution – what he calls “Marx’s dark prophecy.” (Capital in the Twenty-First Century, p.9).

Piketty’s insidious choice of words reflects his own class bias (in favor of the capitalist elites).

Piketty is correct that the European and North American socialist revolutions that many leftists dreamed of didn’t happen in the late 19th or early 20th centuries. Neither did proletarian immiseration on the scale that Marx predicted – at least not in the core Western countries at the center of capitalist development. But why call Marx’s dialectical divination “apocalyptic” and “dark”? Piketty’s word choices strongly suggest elite bias: it’s always been the ruling classes who have most particularly found radical anticapitalists’ ideas catastrophic, for obvious reasons. For socialist, communist, and left anarchist revolutionaries of the mid and late-19th century, the overthrow of private capital and its amoral profits system and the replacement of the capitalist ruling class by the democratic reign of the associated producers and citizens in service to the common good was hardly an apocalypse. It was for them the dawning of the end of the long human pre-history of class rule, ushering in the possibility of a world beyond exploitation and the de facto class dictatorship of privileged owners. It was a “true realm of freedom” beyond endless toil and necessity and “worthy of …‘human nature.’” (Marx, Capital, v.3, p.820). “In the place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms,” Marx and his indispensable comrade Frederick Engels proclaimed in their 1848 Communist Manifesto, “we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.”

The Capitalist Apocalypse That Is

Another, more genuinely dark question arises. Have we really “avoid[ed]” Marxist, well, capitalist apocalypse in the years since Marx wrote? Forget for a moment the cataclysmic global wars, imperial policies, abject plutocracy, and misery of the 20th and early 21st centuries, terrible problems that Marxist and other radical intellectuals reasonably root to no small degree in the system of class rule called capitalism. Never mind the global pauperization that has spread like something out of the Communist Manifesto in the neoliberal era, however much the rich nations may have avoided Piketty’s “Marxist apocalypse.”

Put all that aside for a moment, if you can, and reflect on the growing environmental catastrophe that now poses a genuine threat of human extinction. Marx suggested two stark alternatives in the Manifesto: “either…a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.” Can there be any serious doubt in the current age of accelerating and catastrophic climate change that the very “modern economic growth” that Piketty praises for having kept “the Marxist apocalypse” at bay threatens to bring about “the common ruin of the contending classes” – indeed the degradation and final destruction of life on Earth – because it is taking place under the command of capital? More than merely dangerous, uncomfortable, and expensive, anthropogenic global warming (AGW) threatens the world’s food and water supplies. It raises the very real specter of human extinction if and when terrible “tipping points” like the large-scale release of Arctic methane (a potential near-term context for truly “runaway” warming) are passed. The related problem of ocean acidification (a change in the ocean’s chemistry resulting from excessive human carbon emissions) is attacking the very building blocks of life under the world’s great and polluted seas. Thanks to AGW and other forms of toxic human intervention in global ecology we most add drastically declining biodiversity – a technical phrase for the massive dying off of other species – to the list of “ecological rifts” facing humanity and other living and sentient beings in the 21stcentury.

The findings and judgments of the best contemporary earth science are crystal clear. As the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research (UK) concluded last year: “Today, in 2013, we face an unavoidably radical future…We either continue with rising emissions and reap the radical repercussions of severe climate change, or we acknowledge that we have a choice and pursue radical emission reductions.” Sadly, however, the Tyndall scientists failed to radically confront the social-systemic cancer behind AGW. The deeper disease is capitalism, for whose masters and apologists the answer to the venerable popular demand for equality has long been “more.”[6]The answer is based on the theory that growth creates “a rising tide that lifts all boats” in ways that make us forget about the fact that a wealthy few are sailing luxuriantly in giant yachts while most of us are struggling to keep afloat in modest motorboats and rickety dinghies.

As Le Monde’s ecological editor Herve Kempf noted in his aptly titled book The Rich Are Destroying the Earth (2007), “the oligarchy” sees the pursuit of material growth as “the solution to the social crisis,” the “sole means of fighting poverty and unemployment,” and the “only means of getting societies to accept extreme inequalities without questioning them. . . . Growth,” Kempf explained, “would allow the overall level of wealth to arise and consequently improve the lot of the poor without — and this part is never spelled out [by the economic elite] — any need to modify the distribution of wealth.”

“Growth,” the liberal economist Henry Wallich explained (approvingly) in 1972, “is a substitute for equality of income. So long as there is growth there is hope, and that makes large income differentials tolerable.” (1)

But growth is more than an ideology and a promise to cover inequality under the profits system. It is also a material imperative for investors, managers, workers, and policymakers caught up in the disastrous competitive world-capitalist logic of what the Marxist environmental sociologist John Bellamy Foster calls “the global ‘treadmill of production.” Capitalism demands constant growth to meet the competitive accumulation requirements of capital, the employment needs of an ever-expanding global class or proletarians (workers dependent on wages), the sales needs of corporations, and governing officials’ need to legitimize their power by appearing to advance national economic development and security. This system can no more forego growth and survive than a person can stop breathing and live. It is, as the eco-socialist Joel Kovel notes, a system based on the “eternal expansion of the economic product,” and the “conver [sion of] everything possible [including the air we breathe, the water we drink, the soil and plants] into monetary [exchange] value.”

“The Earth we live on,” Kovel notes, “is finite, and its ecosystems have evolved to accommodate to that finitude. Therefore, a system built on endless growth is going to destroy the integrity of the ecosystems upon which life depends for food, energy, and other resources.” [7]

Consistent with this harsh reality, the system’s leading investors have invested massively in highly wasteful advertising, marketing, packaging and built-in-obsolescence. The commitment has penetrated into core processes of capitalist production, so that millions toil the world over in the making of complex electronic (and other) products designed to lose material and social value (and thus to be dumped in landfills) in short periods of time.[8]

Along the way, U.S. capital has invested huge amounts of fixed capital in the existing fossil fuel-addicted energy system – “sunk” capital investments that make giant and powerful petrochemical corporations and utilities all too “rationally” (from a profit perspective) resistant to a much needed clean energy conversion. And there are more than enough fossil fuels left underground to push the planet past livability before carbon capital’s drillers and frackers run out – something to keep in mind in light of a recent report that methane released from melting permafrost has opened a gigantic crater in Siberia’s Yamal peninsula [9]. Talk about a “specter haunting Europe” (Marx and Engels, 1848) and indeed the whole world.

The same irrational systemic imperatives that drive capitalism into recurrent cycles of boom and bust turn the profits system into a cancerous threat to human existence. The extermination of the species is practically an “institutional imperative” (Noam Chomsky[10]) for the state-capitalist ruling class that imposes the lethal triumph of “exchange value” over “use value” (a key dichotomy in Marx’s analysis) atop the malignant rat-wheel of endless accumulation.

“The World’s Principal Long-Term Worry”

The Jacobin growth and equity advocate Piketty (he reports that high economic and demographic growth rates tend historically to reduce inequality) is not completely unconcerned with the problem. In a brief sub-section of his book, he writes the following: “The second important issue on which [capital accumulation] questions have a major impact is climate change and, more generally, the possibility of deterioration of humanity’s natural capital in the century ahead. If we take a global view then this is clearly the world’s principal long-term worry.” Piketty’s statement comes on page 567, like a tiny afterthought near the end of Capital in the 21st Century, in the volume’s mere three pages that focus on the leading specter haunting humanity in the 21st century, brought to us courtesy of capital. A “global view” would seem to be the view to take when it comes to planetary ecology, but “deterioration of natural capital” is econospeak for eco-cide.

According to the conservative Marxian Meghnad Desai more than a decade ago (in a book provocatively claiming that Marx would have predicted and welcomed the collapse of the Soviet Union), Marx felt that a real and viable socialism would only come after capitalism had exhausted its limits and was no “no longer capable of progress.”[10A] Whatever the accuracy of Desai’s claim regarding Marx (questionable since the mature Marx told Russian radicals they could skip the capitalist stage on the path to socialism), the ecological limits to “progress” under the profits system (private and/or state versions) were passed decades ago. It’s “[eco-] socialism or barbarism if we’re lucky” (Istvan Meszaros): a revolutionary red-green transcendence of continuing bourgeois class rule or a capitalist eco-apocalypse that is right out of Marx.

One can label this stark conclusion as a form dysfunctional “catastrophism” – a nasty term hurled by some Marxians (including the aforementioned Henwood[11]) at those who (like Chomsky) warn of the ever more imminent environmental….well, catastrophe. But to paraphrase and adapt Che Guevera, it’s not my fault if reality is now eco-socialist. “The Earth,” as the young Buddha was reported to have said, “is my [our] witness.”

“Capitalism is Awful but There is Nothing We Can Do About it”

The “catastrophist” matter of capital-o-genic eco-cide aside, what does the neo-Jacobin Piketty recommend in the way of solutions, so as to bring inequality back into the proper bourgeois-revolutionary boundaries of “common utility”? Proclaiming that that the standard liberal-domestic tax, spending and regulatory agenda is now ineffective in the face of capital’s planetary reach, he advocates a measure that is beyond the grasp of any currently existing national or international body: “a global tax on capital”– something Piketty candidly calls “a utopian idea” (Capital in the 21st Century, 515). Only such a worldwide levy “would contain the unlimited growth of global inequality of wealth,” Piketty writes.

Given the monumental logistical and political barriers to the implementation of such a tax, it’s hard not to see Piketty’s heralded Capital as feeding popular pessimism about the existence of any alternatives to the United States’ drift into what former New York State Tax Commissioner James Wezler calls “a plutocratic dystopia characterized by wealth inequality approaching that of ancien régime France.”[12] Piketty feeds the “de facto mental slavery” (David Barsamian[13]) of our time: the widespread sense of powerlessness and isolation shared by millions of citizens and workers and the intimately related idea that there’s no serious or viable replacement for – and nothing much that can be done about – the dominant order.

Given all this and more, including its oversized and tedious nature, why was Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Centurysuch a hit with relatively well-off, highly “educated” and supposedly “left”-leaning US liberals this last spring and summer? Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, got to the heart of the matter last May, at the peak of the Piketty craze. In an email to Columbia University journalism professor Thomas B. Edsall, Baker wrote that “a big part of the appeal is that it allows people to say capitalism is awful but there is nothing that we can do about it.” The author of a comprehensive domestic policy agenda for reducing inequality, Baker told Edsall “that many people will feel that they have done their part after struggling through a lengthy book on economics, and now they can go back to their vacation homes and say it’s all a shame.”[14]

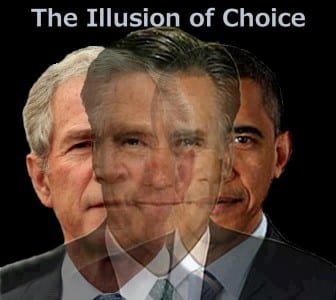

It takes a lot more time and energy to read Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century than it does to vote for Barack Obama. Still, it’s hard to miss the parallel here. Like poking a ballot card for the first half-white US president, purchasing (and maybe even working their way through some or all of) Piketty’s book seems to help some liberals think they’ve made a contribution to solving the world’s injustices even while it asks them to do nothing of substance to fight inequality and justifies that nothingness by suggesting that nothing much can be done anyway.

Alternative Reading

For readers interested in deeper anti-capitalist substance and more than Pikettyan powerlessness, there is no lack of first-rate writing on how to construct a radically transformed and democratized America Beyond Capitalism – title of an important book by the University of Maryland economist Gar Alperovitz. Alperovitz advocates giving workers and communities stakes and self-management through the expansion and support of significantly empowered employee stock ownership and other programs and policies (including highly progressive tax rates and a 25-hour work week) designed to replace the current top-down plutocracy with a bottom-up “pluralist commonwealth.”

Another “utopian” proposal is MIT engineering professor Seymour Melman’s call – developed in his 2001 book After Capitalism and other works—for a nonmarket system of workers’ self-management. Also important: left economist Rick Wolff’s Democracy at Work: A Cure for Capitalism,combining a Marxian analysis of the current economic crisis with a call for “worker self-directed enterprises”; David Schweikert’s After Capitalism,calling for worker self-management combined with national ownership of underlying capital; Michael Liebowitz’s The Socialist Alternative,taking its cue from Latin America’s leftward politics to advance a vision of participatory and democratic socialism; Joel Kovel’s The Enemy of Nature (arguing that solving the current grave environmental crisis requires a shift away from private and corporate control of the planet’s resources); and Michael Albert’s prolific writing and speaking on behalf of participatory economics (“parecon”),inspired to some degree by the “council communism” once advocated by the libertarian Marxist Anton Pannekeok. In his book Parecon: Life After Capitalism (2003), Albert calls for a highly but flexibly structured model of radically democratic economics that organizes work and society around workers’ and consumers councils – richly participatory institutions that involve workers and the entire community in decisions on how resources are allocated, what to produce and how, and how income and work tasks are distributed.

More recently, a sprightly and highly readable Occupy-inspired volume published by a major US publishing house, HarperCollins, is titled IMAGINE Living in a Socialist America (2014). It includes essays from leading intellectuals and activists and provides practical reflections on how numerous spheres of American life and policy – ecology, workplace, finance/investment, criminal justice, gender, sexuality, immigration, welfare, food, housing, health care/medicine, education, art, science, media, and spirituality – might be experienced and transformed under an American version of democratic socialism.

Imagine the lively, inspirational, and forward-looking Imagine and not Piketty’s lumbering, backwards-looking, and pessimism-inducing Capital in the 21st Century (which offers little in the way of solutions and comes up very short on the problem) as the surprise bestseller of 2014. It’s not too late: order your copy here: http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/imagine-frances-goldin/1115888725?ean=9780062305572.

Author and historian Paul Street’s latest book is They Rule: The 1% v. Democracy (order at http://www.paradigmpublishers.com/Books/BookDetail.aspx?productID=367810) Street is the author of “Part I: What’s Wrong with Capitalism?” in IMAGINE Living in a Socialist USA.

K%= Capitalists’ share of income; P%= People’s share; K/i= Capitalists’ per capita annual income; P/i= Ordinary citizen per capita annual income.

| YEAR |

GDP (MM) |

K% |

P% |

K/i ($) |

P/i ($) |

| 1 |

1000 |

10 |

90 |

200,000 |

900 |

| 2 |

1500 |

15 |

85 |

450,000 |

1275 |

| 3 |

1850 |

18 |

82 |

660,000 |

1518 |

| 4 |

2100 |

23 |

77 |

966,000 |

1617 |

| 9 |

6700 |

78 |

22 |

10,452,000 |

1475 |

| 10 |

8300 |

78 |

|

12,948,000 |

1827 |

|

|

|

|

6374% gain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Summation: Selected Endnotes

1. “P”BS Newshour, May 12, 2014, http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/piketty-takes-on-inequality-in-capital/

2. As Marx would certainly note with no small disdain. See Jack Rasmus, “Economists Discover Inequality But Have Yet to Explain It,” Jack Rasmus: Predicting the Global Economic Crisis (May 13, 2014), http://jackrasmus.com/2014/05/13/economists-discover-income-inequality-but-have-yet-to-explain-it/.

3. Noam Chomsky, What Uncle Sam Really Wants (Berkeley, CA: Odonian Press, 1991), 91.

4. Richard Wolff, Democracy at Work: A Cure for Capitalism (Chicago: Haymarket, 2012), 82). For a brilliant left-anarchist historical perspective on the Soviet model (and the broader evolution of capitalist class relations in the workplace), see the formerly radical Stephen Marglin’s classic essay, “What do Bosses Do?,” pp. 13-54 in Andre Gorz, ed., The Division of Labor: The Labour Process and Class Struggle in Modern Capitalism (Humanities Press, NJ, 1976). The Soviet “model” was hardly without real accomplishments. It succeeded in significantly modernizing Russia (the nation that more than any other defeated Hitler’s fascist regime) outside the pure Western capitalist model of privately owned means of production, distribution, transportation, finance, and communications. This was the main reason for U.S.-led Western hostility of the “Soviet specter,” not (following the doctrinal U.S. Cold War line) Russia’s alleged commitment to global revolution, something it abandoned with the exile of Trotsky in the 1920s. On Western/US Cold War complicity in the false description of the USSR as socialist, see Chomsky, Want Uncle Sam Really Wants, 92: “The world’s two major propaganda systems did not agree on much, but they did agree on using the term socialism to refer to the immediate destruction of every element of socialism by the Bolsheviks. That’s not too surprising. The Bolsheviks called their system socialist so as to exploit the moral prestige of socialism. The West adopted the same usage for the opposite reason: to defame the feared libertarian ideals [of workers’ control and true popular governance] by associating them with the Bolshevik dungeon, to undermine the popular belief that there really might be progress towards a more just society with democratic control over its basic institutions and concern for human needs and rights. If socialism is the tyranny of Lenin and Stalin, then sane people will say: not for me. And if that’s the only alternative to corporate state capitalism, then many will submit to its authoritarian structures as the only reasonable choice.”

5. Doug Henwood, “The Top of the World,” Book Forum, April/May 2014, http://www.bookforum.com/inprint/021_01/12987 It is interesting to compare this description of the Soviet model as proof that “an alternative system was possible” with Henwood’s dismissal of Mike Albert’s Parecon – the most elaborate attempt in recent post-Cold War times to develop a comprehensively non-and anti-capitalist economic vision (including non-hierarchical work relations) – as an unhelpful “off-the-shelf utopia.” See Doug Henwood, “A Post-Capitalist Future is Possible,” The Nation, March 13, 2009, http://www.thenation.com/article/post-capitalist-future-possible#. Parecon is a dysfunctional dreamland but the Soviet state-capitalist tyranny shows “that an alternative economic system was possible.”

http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/21215-beyond-growth-or-beyond-capitalism

http://clogic.eserver.org/3-1&2/foster.html; Joel Kovel, Chapter 2: “The Future Will be Ecosocialist Because Without Ecosocialism There Will be No Future,” in Francis Goldin, Debby Smith, and Michael Steven Smith, IMAGINE Living in a Socialist USA (New York: Harper Collins, 2014), 27-28.

8. John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark, “The Planetary Emergency,” Monthly Review (December 2013),http://monthlyreview.org/2012/12/01/the-planetary-emergency

http://www.nature.com/news/mysterious-siberian-crater-attributed-to-methane-1.15649

10. “I do not want to end without mentioning another externality that is dismissed in market systems: the fate of the species. Systemic risk in the financial system can be remedied by the taxpayer, but no one will come to the rescue if the environment is destroyed. That it must be destroyed is close to an institutional imperative.” Noam Chomsky, “Is t he World Too Big to Fail?” TomDispatch (August 20, 2012), www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175581/best_of_tomdispatch%3A_noam_chomsky,_who_owns_the_world_ On the permafrost crater in Siberia, see Nature (July 31, 2014), http://www.nature.com/news/mysterious-siberian-crater-attributed-to-methane-1.15649

10A. Meghnad Desai, Marx’s Revenge: The Resurgence of Capitalism and the Death of State Socialism (New York: Verso, 2002).

11. See the horrid ecological chapter by Eddie Yuen in Sasha Lilley, David McNally, James Davis, Eddie Yuen, and Doug Henwood, Catastrophism: The Apocalyptic Politics of Collapse and Rebirth (PM Press, 2012). For a measured and brilliant response to Yuen, see Ian Angus, “The Myth of ‘Environmental Catastrophism,’” Monthly Review(September 1, 2013), http://monthlyreview.org/2013/09/01/myth-environmental-catastrophism/

12. Wezler is quoted in Thomas B. Edsall, “Thomas Piketty and His Critics,” New York Times, May 14, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/14/opinion/edsall-thomas-piketty-and-his-critics.html?_r=0

13. Noam Chomsky, Power Systems: Interviews with David Barsamian (New York: Metropolitan, 2013), 34.

14. Edsall, “Piketty and his Critics.”

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t is ironic, considering democracy’s pitiful state worldwide that, in accordance to its etymology, it literally means “common people’s rule” or, more simply, “people’s power.” The English term democracy and the 14th-century French word democratie come from the Greek demokratia via the Latin democratia. The Greek radical demos means “common people,” and kratos means “rule, or power.” How did we manage to pervert such a laudable notion of power to the people and diametrically turn it into a global system of rule at large under the principles of oligarchy and plutocracy? Everywhere we look, from east to west and north to south, plutocrats and oligarchs are firmly in charge: puppet masters of the political class. They have transformed democracy into a parody of itself and a toxic form of government. The social contract implied in a democratic form of governance is broken.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t is ironic, considering democracy’s pitiful state worldwide that, in accordance to its etymology, it literally means “common people’s rule” or, more simply, “people’s power.” The English term democracy and the 14th-century French word democratie come from the Greek demokratia via the Latin democratia. The Greek radical demos means “common people,” and kratos means “rule, or power.” How did we manage to pervert such a laudable notion of power to the people and diametrically turn it into a global system of rule at large under the principles of oligarchy and plutocracy? Everywhere we look, from east to west and north to south, plutocrats and oligarchs are firmly in charge: puppet masters of the political class. They have transformed democracy into a parody of itself and a toxic form of government. The social contract implied in a democratic form of governance is broken. The electoral process is an essential part of “the consent of the governed” defined by Rousseau. In almost all of the so-called democratic countries, however, the important act of voting to elect the people’s representatives has become an exercise in futility. Today politicians, who still have the audacity to call themselves public servants, are the obedient executors of the trans-national global corporate elite. These politicians are actors who are cast to perform in opaque screenplays written by top corporate power brokers and marketed to the public like products. In this sad state of affairs that passes for democracy, citizens have become blind consumers of products, which are political figureheads working for global corporate interests. For any organism to remain healthy, it must be able to excrete. The same applies to our collective social body, but instead of regularly eliminating our political residue and flushing it away, we recycle it.

The electoral process is an essential part of “the consent of the governed” defined by Rousseau. In almost all of the so-called democratic countries, however, the important act of voting to elect the people’s representatives has become an exercise in futility. Today politicians, who still have the audacity to call themselves public servants, are the obedient executors of the trans-national global corporate elite. These politicians are actors who are cast to perform in opaque screenplays written by top corporate power brokers and marketed to the public like products. In this sad state of affairs that passes for democracy, citizens have become blind consumers of products, which are political figureheads working for global corporate interests. For any organism to remain healthy, it must be able to excrete. The same applies to our collective social body, but instead of regularly eliminating our political residue and flushing it away, we recycle it.