The Liberal Attack on Naomi Klein and This Changes Everything

Crossing the River of Fire Klein with documentarian Brian Long. (Via @mjb.flickr)

The front cover of Naomi Klein’s new book, This Changes Everything, is designed to look like a protest sign. It consists of the title alone in big block letters, with the emphasis on Changes. Both the author’s name and the subtitle are absent. It is only when we look at the spine of the book, turn it over, or open it to the title page that we see it is written by North America’s leading left climate intellectual-activist and that the subtitle is Capitalism vs. the Climate.1 All of which is clearly meant to convey in no uncertain terms that climate change literally changes everything for today’s society. It threatens to turn the mythical human conquest of nature on its head, endangering present-day civilization and throwing doubt on the long-term survival of Homo sapiens.

The source of this closing circle is not the planet, which operates according to natural laws, but rather the economic and social system in which we live, which treats natural limits as mere barriers to surmount. It is now doing so on a planetary scale, destroying in the process the earth as a place of human habitation. Hence, the change that Klein is most concerned with, and to which her book points, is not climate change itself, but the radical social transformation that must be carried out in order to combat it. We as a species will either radically change the material conditions of our existence or they will be changed far more drastically for us. Klein argues in effect for System Change Not Climate Change—the name adopted by the current ecosocialist movement in the United States.2

In this way Klein, who in No Logo ushered in a new generational critique of commodity culture, and who in The Shock Doctrine established herself as perhaps the most prominent North American critic of neoliberal disaster capitalism, signals that she has now, in William Morris’s famous metaphor, crossed “the river of fire” to become a critic of capital as a system.3 The reason is climate change, including the fact that we have waited too long to address it, and the reality that nothing short of an ecological revolution will now do the job.

In the age of climate change, Klein argues, a system based on ever-expanding capital accumulation and exponential economic growth is no longer compatible with human well-being and progress—or even with human survival over the long run. We need therefore to reconstruct society along lines that go against the endless amassing of wealth as the primary goal. Society must be rebuilt on the basis of other principles, including the “regeneration” of life itself and what she calls “ferocious love.”4 This reversal in the existing social relations of production must begin immediately with a war on the fossil-fuel industry and the economic growth imperative—when such growth means more carbon emissions, more inequality, and more alienation of our humanity.

Klein’s crossing of the river of fire has led to a host of liberal attacks on This Changes Everything, often couched as criticisms emanating from the left. These establishment criticisms of her work, we will demonstrate, are disingenuous, having little to do with serious confrontation with her analysis. Rather, their primary purpose is to rein in her ideas, bringing them into conformity with received opinion. If that should prove impossible, the next step is to exclude her ideas from the conversation. However, her message represents the growing consciousness of the need for epochal change, and as such is not easily suppressed.

The Global Climateric

The core argument of This Changes Everything is a historical one. If climate change had been addressed seriously in the 1960s, when scientists first raised the issue in a major way, or even in the late 1980s and early ’90s, when James Hansen gave his famous testimony in Congress on global warming, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was first established, and the Kyoto Protocol introduced, the problem could conceivably have been addressed without a complete shakeup of the system. At that historical moment, Klein suggests, it would still have been possible to cut emissions by at most 2 percent a year.5

Today such incremental solutions are no longer conceivable even in theory. The numbers are clear. Over 586 billion metric tons of carbon have been emitted into the atmosphere. To avoid a 2°C (3.6°F) increase in global average temperature—the edge of the cliff for the climate—it is necessary to stay below a trillion metric tons in cumulative carbon emissions. At the present rate of carbon emissions it is estimated that we will arrive at the one trillionth metric ton—equivalent to the 2°C mark—in less than a quarter century, around 2039.6 Once this point is reached, scientists fear that there is a high probability that feedback mechanisms will come into play with reverberations so great that we will no longer be able to control where the thermometer stops in the end. If the world as it exists today is still to avoid the 2°C increase—and the more dangerous 4°C, the point at which disruption to life on the planet will be so great that civilization may no longer be possible—real revolutionary ecological change, unleashing the full power of an organized and rebellious humanity, is required.

What is necessary first and foremost is the cessation of fossil-fuel combustion, bringing to a rapid end the energy regime that has dominated since the Industrial Revolution. Simple arithmetic tells us that there is no way to get down to the necessary zero emissions level, i.e., the complete cessation of fossil-fuel combustion, in the next few decades without implementing some kind of planned moratorium on economic growth, requiring shrinking capital formation and reduced consumption in the richest countries of the world system. We have no choice but to slam on the brakes and come to a dead stop with respect to carbon emissions before we go over the climate cliff. Never before in human history has civilization faced so daunting a challenge.

Klein draws here on the argument of Kevin Anderson, of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change in Britain, who indicates that rich countries will need to cut carbon emissions by 8–10 percent a year. “Our ongoing and collective carbon profligacy,” Anderson writes, “has squandered any opportunity for ‘evolutionary change’ afforded by our earlier (and larger) 2°C budget. Today, after two decades of bluff and lies, the remaining 2°C budget demands revolutionary change to the political and economic hegemony.”7

Instead of addressing climate change when it first became critical in the 1990s, the world turned to the intensification of neoliberal globalization, notably through the creation of the World Trade Organization. It was the very success of the neoliberal campaign to remove most constraints on the operations of capitalism, and the negative effect that this had on all attempts to address the climate problem, Klein contends, that has made “revolutionary levels of transformation” of the system the only real hope in avoiding “climate chaos.”8 “As a result,” she explains,

we now find ourselves in a very difficult and slightly ironic position. Because of those decades of hardcore emitting exactly when we were supposed to be cutting back, the things that we must do to avoid catastrophic warming are no longer just in conflict with the particular strain of deregulated capitalism that triumphed in the 1980s. They are now in conflict with the fundamental imperative at the heart of our economic model: grow or die….

Our economy is at war with many forms of life on earth, including human life. What the climate needs to avoid collapse is a contraction in humanity’s use of resources; what our economic model demands to avoid collapse is unfettered expansion. Only one of these sets of rules can be changed, and it’s not the laws of nature….

Because of our lost decades, it is time to turn this around now. Is it possible? Absolutely. Is it possible without challenging the fundamental logic of deregulated capitalism? Not a chance.9

Of course, “the fundamental logic of deregulated capitalism” is simply a roundabout way of pointing to the fundamental logic of capitalism itself, its underlying drive toward capital accumulation, which is hardly constrained at all in its accumulation function even in the case of a strong regulatory environment. Instead, the state in a capitalist society generally seeks to free up opportunities for capital accumulation on behalf of the system as a whole, rationalizing market relations so as to achieve greater overall, long-run expansion. As Paul Sweezy noted nearly three-quarters of a century ago in The Theory of Capitalist Development, “Speaking historically, control over capitalist accumulation has never for a moment been regarded as a concern of the state; economic legislation has rather had the aim of blunting class antagonisms, so that accumulation, the normal aim of capitalist behavior, could go forward smoothly and uninterruptedly.”10

To be sure, Klein herself occasionally seems to lose sight of this basic fact, defining capitalism at one point as “consumption for consumption’s sake,” thus failing to perceive the Galbraith dependence effect, whereby the conditions under which we consume are structurally determined by the conditions under which we produce.11 Nevertheless, the recognition that capital accumulation or the drive for economic growth is the defining property, not a mere attribute, of the system underlies her entire argument. Recognition of this systemic property led the great conservative economist Joseph Schumpeter to declare: “Stationary capitalism would be a contradictio in adjecto.”12

It follows that no mere technological wizardry—of the kind ideologically promoted, for example, by the Breakthrough Institute—will prevent us from breaking the carbon budget within several decades, as long as the driving force of the reigning socioeconomic system is its own self-expansion. Mere improvements in carbon efficiency are too small as long as the scale of production is increasing, which has the effect of expanding the absolute level of carbon dioxide emitted. The inevitable conclusion is that we must rapidly reorganize society on other principles than that of stoking the engine of capital with fossil fuels.

None of this, Klein assures us, is cause for despair. Rather, confronting this harsh reality head on allows us to define the strategic context in which the struggle to prevent climate change must be fought. It is not primarily a technological problem unless one is trying to square the circle: seeking to reconcile expanding capital accumulation with the preservation of the climate. In fact, all sorts of practical solutions to climate change exist at present and are consistent with the enhancement of individual well-being and growth of human community. We can begin immediately to implement the necessary changes such as: democratic planning at all levels of society; introduction of sustainable energy technology; heightened public transportation; reductions in economic and ecological waste; a slowdown in the treadmill of production; redistribution of wealth and power; and above all an emphasis on sustainable human development.13

There are ample historical precedents. We could have a crash program, as in wartime, where populations sacrificed for the common good. In England during the Second World War, Klein observes, driving automobiles virtually ceased. In the United States, the automobile industry was converted in the space of half a year from producing cars to manufacturing trucks, tanks, and planes for the war machine. The necessary rationing—since the price system recognizes nothing but money—can be carried out in an egalitarian manner. Indeed, the purpose of rationing is always to share the sacrifices that have to be made when resources are constrained, and thus it can create a sense of real community, of all being in this together, in responding to a genuine emergency. Although Klein does not refer to it, one of the most inspiring historical examples of this was the slogan “Everyone Eats the Same” introduced in the initial phases of the Cuban Revolution and followed to an extraordinary extent throughout the society. Further, wartime mobilization and rationing are not the only historical examples on which we can draw. The New Deal in the United States, she indicates, focused on public investment and direct promotion of the public good, aimed at the enhancement of use values rather than exchange values.14

Mainstream critics of This Changes Everything often willfully confuse its emphasis on degrowth with the austerity policies associated with neoliberalism. However, Klein’s perspective, as we have seen, could not be more different, since it is about the rational use of resources under conditions of absolute necessity and the promotion of equality and community. Nevertheless, she could strengthen her case in this respect by drawing on monopoly-capital theory and its critique of the prodigious waste in our economy, whereby only a miniscule proportion of production and human labor is now devoted to actual human needs as opposed to market-generated wants. As the author of No Logo, Klein is well aware of the marketing madness that characterizes the contemporary commodity economy, causing the United States alone to spend more than a trillion dollars a year on the sales effort.15

What is required in a rich country such as the United States at present, as detailed in This Changes Everything, is not an abandonment of all the comforts of civilization but a reversion to the standard of living of the 1970s—two decades into what Galbraith dubbed “the affluent society.” A return to a lower per capita output (in GDP terms) could be made feasible with redistribution of income and wealth, social planning, decreases in working time, and universal satisfaction of genuine human needs (a sustainable environment; clean air and water; ample food, clothing, and shelter; and high-quality health care, education, public transportation, and community-cultural life) such that most people would experience a substantial improvement in their daily lives.16 What Klein envisions here would truly be an ecological-cultural revolution. All that is really required, since the necessary technological means already exist, is people power: the democratic mass mobilization of the population.

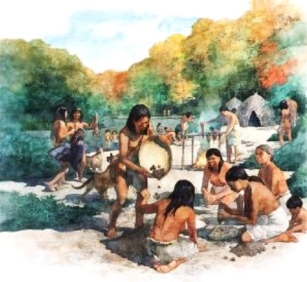

Such people power, Klein is convinced, is already emerging in the context of the present planetary emergency. It can be seen in the massive but diffuse social-environmental movement, stretching across the globe, representing the struggles of tens of millions of activists worldwide, to which she gives (or rather takes from the movement itself) the name Blockadia. Numberless individuals are putting themselves on the line, confronting power, and frequently facing arrest, in their opposition to the fossil-fuel industry and capitalism itself. Indigenous peoples are organizing worldwide and taking a leading role in the environmental revolt, as in the Idle No More movement in Canada. Anti-systemic, ecologically motivated struggles are on the rise on every continent.

The primary burden for mitigating climate change necessarily resides with the rich countries, which are historically responsible for the great bulk of the carbon added to the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution and still emit the most carbon per capita today. The disproportionate responsibility of these nations for climate change is even greater once the final consumption of goods is factored into the accounting. Poor countries are heavily dependent on producing export goods for multinational corporations to be sold to consumers at the center of the world capitalist economy. Hence, the carbon emissions associated with such exports are rightly assigned to the rich nations importing these goods rather than the poor ones exporting them. Moreover, the rich countries have ample resources available to address the problem and carry out the necessary process of social regeneration without seriously compromising the basic welfare of their populations. In these societies, the problem is no longer one of increasing per capita wealth, but rather one of the rational, sustainable, and just organization of society. Klein evokes the spirit of Seattle in 1999 and Occupy Wall Street in 2011 to argue that sparks igniting radical ecological change exist even in North America, where growing numbers of people are prepared to join a global peoples’ alliance. Essential to the overall struggle, she insists, is the explicit recognition of ecological or climate debt owed by the global North to the global South.17

The left is not spared critical scrutiny in Klein’s work. She acknowledges the existence of a powerful ecological critique within Marxism, and quotes Marx on “capitalism’s ‘irreparable rift’ with ‘the natural laws of life itself.‘” Nevertheless, she points to the high carbon emissions of Soviet-type societies, and the heavy dependence of the economies of Bolivia and Venezuela on natural resource extraction, notwithstanding the many social justice initiatives they have introduced. She questions the support given by Greece’s SYRIZA Party to offshore oil exploration in the Aegean. Many of those on the left, and particularly the so-called liberal-left, with their Keynesian predilections, continue to see an expansion of the treadmill of production, even in the rich countries, as the sole means of social advance.18 Klein’s criticisms here are important, but could have benefited, with respect to the periphery, from a consideration of the structure of the imperialist world economy, which is designed specifically to close off options to the poorer countries and force them to meet the needs of the richer ones. This creates a trap that even a Movement Toward Socialism with deep ecological and indigenous values like that of present-day Bolivia cannot seek to overcome without deep contradictions.19

“The unfinished business of liberation,” Klein counsels, requires “a process of rebuilding and reinventing the very idea of the collective, the communal, the commons, the civil, and the civic after so many decades of attack and neglect.”20 To accomplish this, it is necessary to build the greatest mass movement of humanity for revolutionary change that the world has ever seen: a challenge that is captured in the title to her conclusion: “The Leap Years: Just Enough Time for Impossible.” If this seems utopian, her answer would be that the world is heading towards something worse than mere dystopia: unending, cumulative, climate catastrophe, threatening civilization and countless species, including our own.21

Liberal Critics as Gatekeepers

Confronted with Klein’s powerful argument in This Changes Everything, liberal pundits have rushed to rein in her arguments so that her ideas are less in conflict with the system. Even where the issue is planetary ecological catastrophe, imperiling hundreds of millions of people, future generations, civilization, and the human species itself, the inviolable rule remains the same: the permanency of capitalism is not to be questioned.

As Noam Chomsky explains, liberal opinion plays a vital gatekeeping role for the system, defining itself as the rational left of center, and constituting the outer boundaries of received opinion. Since most of the populace in the United States and the world as a whole is objectively at odds with the regime of capital, it is crucial to the central propaganda function of the media to declare as “off limits” any position that questions the foundations of the system itself. The media effectively says: “Thus far and no further.” To venture farther left beyond the narrow confines of what is permitted within liberal discourse is deemed equivalent to taking “off from the planet.”22

In the case of an influential radical journalist, activist, and best-selling author, like Klein, liberal critics seek first and foremost to refashion her message in ways compatible with the system. They offer her the opportunity to remain within the liberal fraternity—if she will only agree to conform to its rules. The aim is not simply to contain Klein herself but also the movement as a whole that she represents. Thus we find expressions of sympathy for what is presented as her general outlook. Accompanying all such praise, however, is a subtle recasting of her argument in order to blunt its criticism of the system. For example, it is perfectly permissible on liberal grounds to criticize neoliberal disaster capitalism, as an extreme policy regime. This should at no time, however, extend to a blanket critique of capitalism. Liberal discussions of This Changes Everything, insofar as they are positive at all, are careful to interpret it as adhering to the former position.

Yet, the very same seemingly soft-spoken liberal pundits are not above simultaneously brandishing a big stick at the slightest sign of transgression of the Thus Far and No Further principle. If it should turn out that Klein is really serious in arguing that “this changes everything” and actually sees our reality as one of “capitalism vs. the climate,” then, we are told, she has Taken Off From the Planet, and has lost her right to be heard within the mass media or to be considered part of the conversation at all. The aim here is to issue a stern warning—to remind everyone of the rules by which the game is played, and the serious sanctions to be imposed on those not conforming. The penalty for too great a deviation in this respect is excommunication from the mainstream, to be enforced by the corporate media. Noam Chomsky may be the most influential intellectual figure alive in the world today, but he is generally considered beyond the pale and thus persona non grata where the U.S. media is concerned.

None of this of course is new. Invited to speak at University College, Oxford in 1883, with his great friend John Ruskin in the chair, William Morris, Victorian England’s celebrated artist, master-artisan, and epic poet, author of The Earthly Paradise, shocked his audience by publicly declaring himself “one of the people called Socialists.” The guardians of the official order (the Podsnaps of Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend) immediately rose up to denounce him—overriding Ruskin’s protests—declaring that if they had known of Morris’s intentions he would not have been given loan of the hall. They gave notice then and there that he was no longer welcome at Oxford or in establishment circles. As historian E.P. Thompson put it, “Morris had crossed the ‘river of fire.’ And the campaign to silence him had begun.”23

Klein, however, presents a special problem for today’s gatekeepers. Her opposition to the logic of capital in This Changes Everything is not couched primarily in the traditional terms of the left, concerned mainly with issues of exploitation. Rather, she makes it clear that what has finally induced her to cross the river of fire is an impending threat to the survival of civilization and humanity itself. She calls for a broad revolt of humanity against capitalism and for the creation of a more sustainable society in response to the epochal challenge of our time. This is an altogether different kind of animal—one that liberals cannot dismiss out of hand without seeming to go against the scientific consensus and concern for humanity as a whole.

“The task from a ruling-class governing perspective is to find a way to contain or neutralize Klein’s views and those of the entire radical climate movement…”

Further complicating matters, Klein upsets the existing order of things in her book by declaring “the right is right.” By this she means that the political right’s position on climate change is largely motivated by what it correctly sees as an Either/Or question of capitalism vs. the climate. Hence, conservatives seek to deny climate change—even rejecting the science—in their determination to defend capitalism. In contrast, liberal ideologues—caught in the selfsame trap of capitalism vs. the climate—tend to waffle, accepting most of the science, while turning around and contradicting themselves by downplaying the logical implications for society. They pretend that there are easy, virtually painless, non-disruptive ways out of this trap via still undeveloped technology, market magic, and mild government regulation—presumably allowing climate change to be mitigated without seriously affecting the capitalist economy. Rather than accepting the Either/Or of capitalism against the climate, liberals convert the problem into one of neoliberalism vs. the climate, insisting that greater regulation, including such measures as carbon trading and carbon offsets, constitutes the solution, with no need to address the fundamental logic of the economic and social system.

Ultimately, it is this liberal form of denialism that is the more dangerous since it denies the social dimension of the problem and blocks the necessary social solutions. Hence, it is the liberal view that is the main target of Klein’s book. In a wider sense, though, conservatives and liberals can be seen as mutually taking part in a dance in which they join hands to block any solution that requires going against the system. The conservative Tweedle Dums dance to the tune that the cost of addressing climate change is too high and threatens the capitalist system. Hence, the science that points to the problem must be denied. The liberal Tweedle Dees dance to the tune that the science is correct, but that the whole problem can readily be solved with a few virtually costless tweaks here and there, put into place by a new regulatory regime. Hence, the system itself is never an issue.

It is her constant exposure of this establishment farce that makes Klein’s criticism so dangerous. She demands that the gates be flung open and the room for democratic political and social maneuver be expanded enormously. What is needed, for starters, is a pro-democracy movement not simply in the periphery of the capitalist world but at the center of the system itself, where the global plutocracy has its main headquarters.

The task from a ruling-class governing perspective, then, is to find a way to contain or neutralize Klein’s views and those of the entire radical climate movement. The ideas she represents are to be included in the corporate media conversation only under extreme sufferance, and then only insofar as they can be corralled and rebranded to fit within a generally liberal, reformist perspective: one that does not threaten the class-based system of capital accumulation.

Rob Nixon can be credited with laying out the general liberal strategy in this respect in a review of Klein’s book in the New York Times. He declares outright that Klein has written “the most momentous and contentious environmental book since ‘Silent Spring.‘” He strongly applauds her for her criticisms of climate change deniers, and for revealing how industry has corrupted the political process, delaying climate action. All of this, however, is preliminary to his attempt to rein in her argument. There is a serious flaw in her book, we are told, evident in her subtitle, Capitalism vs. the Climate. “What’s with the subtitle?” he scornfully asks. Then stepping in as Klein’s friend and protector, Nixon tells New York Times readers that the subtitle is simply a mistake, to be ignored. We should not be thrown off, he proclaims, by a “subtitle” that “sounds like a P.R. person’s idea of a marquee cage fight.” Rather, “Klein’s adversary is neoliberalism—the extreme capitalism that has birthed our era of extreme extraction.” In this subtle recasting of her argument, Klein reemerges as a mere critic of capitalist excess, rejecting specific attributes taken on by the system in its neoliberal phase that can be easily discarded, and that do not touch the system’s fundamental properties. Her goal, we are told, is the same as in The Shock Doctrine: turning back the neoliberal “counterrevolution,” returning us to a more humane Golden Age liberal order. Her subtitle can therefore be dismissed in its entirety, as it “belies the sophistication” of her work: code for her supposed conformity to the Thus Far and No Further principle. Employing ridicule as a gatekeeping device—with the implication that this is the sorry fate that awaits anyone who transgresses Thus Far and No Further—Nixon states that “Klein is smart and pragmatic enough to shun the never-never land of capitalism’s global overthrow.”24

25

Approaching This Changes Everything much more bluntly, Elizabeth Kolbert, writing for the New York Review of Books, quickly lets us know that she has not come to praise Klein but to bury her. Klein’s references to conservation, “managed degrowth,” and the need to shrink humanity’s ecological footprint, Kolbert says, are all non-marketable ideas, to be condemned on straightforwardly capitalist-consumerist principles. Such strategies and actions will not sell to today’s consumers, even if the future of coming generations is in jeopardy. Nothing will get people to give up “HDTV or trips to the mall or the family car.” Unless it is demonstrated how acting on climate change will result in a “minimal disruption to ‘the American way of life,‘”she asserts, nothing said with respect to climate change action matters at all. Klein has simply provided a convenient “fable” of little real value. This Changes Everything is indicted for having violated accepted commercial axioms in its core thesis, which Kolbert converts into an argument for extreme austerity. Klein is to be faulted for her grandiose schemes that do not fit into U.S. consumer society, and for not “looking at all closely at what this [reduction in the commodity economy] would entail.” Klein has failed to specify exactly how many watts of electricity per capita will be consumed under her plan. It is much easier, Kolbert seems to say, for U.S. consumers to imagine the end of a climate permitting human survival than to envision the end of two-million-square-foot shopping malls.26

David Ulin in the Los Angeles Times unveils still another weapon in the liberal arsenal, denouncing Klein for her optimism and her faith in humanity. “There is, in places,” he emphasizes, “a disconnect between her [Klein’s] idealism and her realism, what she thinks ought to happen and what she recognizes likely will.” Social analysis, in Ulin’s view, seems to be reduced to forecasting the most likely outcomes. Klein apparently failed to consult with Las Vegas oddsmakers before making her case for saving humanity. Klein’s penchant for idealism, he declares, “is most glaring in her suggestions for large-scale policy mitigation, which can seem simplistic, relying on notions of fairness…that corporate culture does not share.” Regrettably, Ulin does not tell us exactly where the kind of climate justice programs put in place by Exxon and Walmart’s “corporate culture” will actually lead us in the end. However, he does give us a specious clue in his final paragraph, describing what he apparently considers to be the most realistic scenario. The planet, we are informed, “has ample power to rock, burn, and shake us off completely.” The earth will go on without us.27

Other liberal gatekeepers pull out all the stops, attacking not just every radical notion in Klein’s book but the book as a whole, and even Klein herself. Writing for the influential liberal news and opinion website, the Daily Beast, Michael Signer characterizes Klein’s book as “a curiously clueless manifesto.” It will not spark a movement against carbon, in part because Klein “rejects capitalism, market mechanisms, and even, seemingly, profit motives and corporate governance.” She offers “a compelling story,” but one that “creates the paradoxical effect of making this perspicacious and successful author seem like an idiot.” Signer depicts her as if she has Taken Off From the Planet simply by refusing to stay within the narrow spectrum of opinion defined by the Wall Street Journal on the one side and the New York Times on the other. “For anyone who believes in capitalism and political leadership,” we are informed, “her book won’t change anything at all.”28

Mark Jaccard, an orthodox economist writing for the Literary Review of Canada, declares that This Changes Everything ignores how market-based mechanisms are a powerful means for reducing carbon emissions. However, his main evidence for this contention is Arnold Schwarzenegger’s signing of a climate bill in California in 2006, which is supposed to reduce the state’s carbon emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. Unfortunately for Jaccard’s claim, a little over a week before he criticized Klein on the basis of the California experiment, the Los Angeles Times broke the story that California’s emissions reduction initiative was in some respects a “shell game,” as California was reducing emissions on paper while emissions were growing in surrounding states from which California was also increasingly purchasing power.29Add to this the facts that California’s initiative is more state-based than capital-based, and that the real problem is not one of getting down to 1990 level emissions, but getting down to pre-1760 level emissions, i.e., carbon emissions eventually have to fall to zero—and not just in California but worldwide.

Jaccard goes on to accuse Klein of wearing “‘blame capitalism’ blinders” that keep her from seeing the actual difficulties that make dealing with climate so imposing. This includes her failure to perceive the “Faustian dilemma” associated with fossil fuels, given that they have yielded so many benefits for humanity and can offer many more to the poor of the world. “This dilemma,” which he is so proud to have discovered, “is not the fault of capitalism.” Indeed, capitalist economics, we are told, is already well equipped to solve the climate problem and only misguided state policies stand in the way. Drawing upon an argument presented by Paul Krugman in his New York Times column, Jaccard suggests that “greenhouse gas reductions have proven to be not nearly as costly as science deniers on the right and anti-growth activists on the left would have us believe.” Krugman, a Tweedle Dee, rejects the carefree Tweedle Dum melody whereby climate change, as a threat to the system, is simply wished away along with the science. He counters this simple, carefree tune with what he regards as a more complex, harmonious song in which the problem is whisked away in spite of the science by means of a few virtually costless market regulations. So convinced is Jaccard himself of capitalism’s basic harmonious relation to the climate that he simply turns a deaf ear to Klein’s impressive account of the vast system-scale changes required to stop climate change.30

Will Boisvert, commenting on behalf of the self-described “post-environmentalist” Breakthrough Institute, condemns Klein and the entire environmental movement in an article pointedly entitled, “The Left vs. the Climate: Why Progressives Should Reject Naomi Klein’s Pastoral Fantasy—and Embrace Our High Energy Planet.” Apparently it is not industry that is destroying a livable climate through its carbon dioxide emissions, but rather environmentalists, by refusing to adopt the Breakthrough Institute’s technological crusade for surmounting nature’s limits on a planetary scale. As Breakthrough senior fellow Bruno Latour writes in an article for the Institute, it is necessary “to love your monsters,” meaning the kind of Frankenstein creations envisioned in Mary Shelley’s novel. Humanity should be prepared to put its full trust, the Breakthrough Institute tells us, in such wondrous technological answers as nuclear power, “clean coal,” geoengineering, and fracking. For its skepticism regarding such technologies, the whole left (and much of the scientific community) is branded as a bunch of Luddites. As Boisvert exclaims in terms designed to delight the entire corporate sector:

Boisvert here echoes Erle Ellis, who, in an earlier essay for the Breakthrough Institute, contended that climate change is not a catastrophic threat, because “human systems are prepared to adapt to and prosper in the hotter, less biodiverse planet that we are busily creating.” On this basis, Boisvert chastises Klein and all who think like her for refusing to celebrate capitalism’s creative destruction of everything in existence.32

Klein of course is not caught completely unaware by such attacks. For those imbued in the values of the current system, she writes in her book, “changing the earth’s climate in ways that will be chaotic and disastrous is easier to accept than the prospect of changing the fundamental, growth-based, profit-seeking logic of capitalism.”33 Indeed, all of the mainstream challenges to This Changes Everything discussed above have one thing in common: they insist that capitalism is the “end of history,” and that the buildup of carbon in the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution and the threat that this represents to life as we know it change nothing about today’s Panglossian best of all possible worlds.

The Ultimate Line of Defense

Naturally, it is not simply liberals, but also socialists, in some cases, who have attacked This Changes Everything. Socialist critics, though far more sympathetic with her analysis, are inclined to fault her book for not being explicit enough about the nature of system change, the full scale of the transformations required, and the need for socialism.34 Klein says little about the vital question of the working class, without which the revolutionary changes she envisions are impossible. It is therefore necessary to ask: To what extent is the ultimate goal to build a new movement toward socialism, a society to be controlled by the associated producers? Such questions still remain unanswered by the left climate movement and by Klein herself.

In our view, though, it is difficult to fault Klein for her silences in this respect. Her aim at present is clearly confined to the urgent and strategic—if more limited—one of making the broad case for System Change Not Climate Change. Millions of people, she believes, are crossing or are on the brink of crossing the river of fire. Capitalism, they charge, is now obsolete, since it is no longer compatible either with our survival as a species or our welfare as individual human beings. Hence, we need to build society anew in our time with all the human creativity and collective imagination at our disposal. It is this burgeoning global movement that is now demanding anti-capitalist and post-capitalist solutions. Klein sees herself merely as the people’s megaphone in this respect. The goal, she explains, is a complex social one of fusing all of the many anti-systemic movements of the left. The struggle to save a habitable earth is humanity’s ultimate line of defense—but one that at the same time requires that we take the offensive, finding ways to move forward collectively, extending the boundaries of liberated space. David Harvey usefully describes this fusion of movements as a co-revolutionary strategy.35

Is the vision presented in This Changes Everything compatible with a classical socialist position? Given the deep ecological commitments displayed by Marx, Engels, and Morris, there is little room for doubt—which is not to deny that socialists need to engage in self-criticism, given past failures to implement ecological values and the new challenges that characterize our epoch. Yet, the whole question strikes us in a way as a bit odd, since historical materialism does not represent a rigid, set position, but is rather the ongoing struggle for a world of substantive equality and sustainable human development. As Morris wrote in A Dream of John Ball:

In this “soft and clear voice,” Ball, a leader in the fourteenth-century English Peasant’s Revolt, proceeded, in Morris’s retelling, to declare that the one true end was “Fellowship on earth”—an end that was also the movement of the people and could never be stopped.36

Klein offers us anew this same vision of human community borne of an epoch of revolutionary change. “There is little doubt,” she declares in her own clear voice, that another crisis will see us in the streets and squares once again, taking us all by surprise. The real question is what progressive forces will make of that moment, the power and confidence with which it will be seized. Because these moments when the impossible seems suddenly possible are excruciatingly rare and precious. That means more must be made of them. The next time one arises, it must be harnessed not only to denounce the world as it is, and build fleeting pockets of liberated space. It must be the catalyst to actually build the world that will keep us all safe. The stakes are simply too high, and time too short, to settle for anything less.37

The ultimate goal of course is not simply “to build the world that will keep us all safe” but to build a world of genuine equality and human community—the only conceivable basis for sustainable human development. Equality, Simón Bolívar exclaimed, is “the law of laws.”38

is editor of Monthly Review and professor of sociology at the University of Oregon. is associate professor of sociology at the University of Utah and co-author of The Tragedy of the Commodity(Rutgers University Press, forthcoming).

Notes

- ↩Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014), “‘A Feeling It’s Gonna Be Huge: Naomi Klein on People’s Climate Eve” (interview), Common Dreams, September 21, 2014, http://commondreams.org.

- System Change Not Climate Change, http://systemchangenotclimatechange.org; Klein, This Changes Everything, 87–89.

- William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976), 244; Naomi Klein, No Logo (New York: Picador, 2002), The Shock Doctrine (New York: Henry Holt, 2007).

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 342, 444–47.

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 55.

- Huffington Post, October 4, 2013, http://huffingtonpost.com; Myles Allen, et. al., “The Exit Strategy,” Nature Reports Climate Change, April 30, 2009, http://nature.com, 56–58. It should be noted that the trillionth metric ton calculation is based on carbon, not carbon dioxide. Moreover, the 2039 estimate of the point at which the trillion metric ton will be reached, made by trillionthtonne.org (sponsored by scientists at Oxford University), should be regarded as quite optimistic under present, business-as-usual conditions, since less than three years ago, at the end of 2012, it was estimated that the trillion ton would be reached in 2043, or in thirty-one years. (See John Bellamy Foster and Brett Clark, “The Planetary Emergency,” Monthly Review 64, no. 7 [December 2012]: 2.) The gap, according to these estimates, is thus closing faster as time passes and nothing is done to reduce emissions.

- http://kevinanderson.info.

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 19, 56. The fact that neoliberal globalization and the creation of the WTO had permanently derailed the movement associated with the Earth Summit in Rio in 1993, including the attempt to prevent climate change, was stressed by one of us more than a dozen years ago at the World Summit for Sustainable Development in Johannesburg 2002, when Klein was present. See John Bellamy Foster, “A Planetary Defeat: The Failure of Global Environmental Reform,” Monthly Review 54, no. 8 (January 2003): 1–9, originally based on several talks delivered in Johannesburg, August 2002.

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 21–24.

- ↩Paul M. Sweezy, The Theory of Capitalist Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 1942), 349.

- The Affluent Society (New York: New American Library, 1984), 121–28. As the author of No Logo, Klein is of course aware of the contradictions of consumption under capitalist commodity production.

- ↩Joseph A. Schumpeter, Essays (Cambridge: Addison-Wesley, 1951), 293.

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 57–58, 115, 479–80.

- Monthly Review 16, no. 6 (October 1964): 69; John Bellamy Foster, “James Hansen and the Climate-Change Exit Strategy,” Monthly Review 64, no. 9 (February 2013): 13.

- The Consumer Trap (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 1.

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 91–94.

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 381–82, 408–13.

- The Dangerous Myths of ‘Anti-Extractivism’,” May 19, 2014, http://climateandcapitalism.com. As the author of The Shock Doctrine, Klein is cognizant of imperialism but it does not enter in her analysis much here, partly because she is making a point of being balanced by criticizing the left as well as the right.

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 458–60.

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 43, 58–63.

- ↩Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media (New York: Black Rose Books, 1994), 58. On the “off limits” notion see Robert W. McChesney and John Bellamy Foster, “Capitalism: The Absurd System,” Monthly Review 62, no. 2 (June 2010): 2.

- Collected Works, vol. 23, 172.

- ↩Rob Nixon, “Naomi Klein’s ‘This Changes Everything,’” New York Times, November 6, 2014, http://nytimes.com.

- ↩Dave Pruett, “A Line in the Tar Sands: Naomi Klein on the Climate,” Huffington Post, November 26, 2014, http://huffingtonpost.com.

- Can Climate Change Cure Capitalism?: An Exchange,” New York Review of Books, January 8, 2015, http:// nybooks.com.

- ↩David L. Ulin, “In ‘This Changes Everything,’ Naomi Klein Sounds Climate Alarm,” Los Angeles Times, September 12, 2014, http://touch.latimes.com.

- ↩Michael Signer, “Naomi Klein’s ‘This Changes Everything’ Will Change Nothing,” Daily Beast, November 17, 2014, http://thedailybeast.com.

- Despite California Climate Law, Carbon Emissions May be a Shell Game,” Los Angeles Times, October 25, 2014, http://latimes.com.

- Errors and Emissions,” New York Times, September 8, 2014, http://nytimes.com.

- Love Your Monsters,” The Breakthrough no. 2, Fall 2011, http://thebreakthrough. Klein herself situates the Breakthrough Institute within her criticism of the right, questioning its claim to progressive values. Klein, This Changes Everything, 57.

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 89.

- ↩See the important analysis in Richard Smith, “Climate Crisis, the Deindustrialization Imperative and the Jobs vs. Environment Dilemma,” Truthout, November 12, 2014, http://truth-out.org.

- ↩David Harvey, The Engima of Capital (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 228–35.

- ↩William Morris, Three Works (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1986).

- ↩Klein, This Changes Everything, 466.

- ↩Símon Bólivar, “Message to the Congress of Bolivia, May 25, 1826,” Selected Works, vol. 2 (New York: The Colonial Press, 1951), 603.

What is $1 a month to support one of the greatest publications on the Left?

Many people feel overwhelmed, because our problems seem so numerous —

Many people feel overwhelmed, because our problems seem so numerous —

everything of importance, and that’s still our

everything of importance, and that’s still our  This attitude isn’t greedy: It doesn’t demand anything from others. Its symmetry makes it an instance of the Golden Rule, “treat others as you wish to be treated,” often touted as our society’s highest morality, but it’s a rather negative version of that rule: I won’t care about you, and I don’t wish for you to care about me. Ayn Rand presented selfishness as a logical philosophy, and independence as a heroic way of life. Her followers believe that it’s possible to respect other people without actually caring about them or being interdependent with them — but they’re mistaken. When we don’t care about something, we see it as an object to be used.

This attitude isn’t greedy: It doesn’t demand anything from others. Its symmetry makes it an instance of the Golden Rule, “treat others as you wish to be treated,” often touted as our society’s highest morality, but it’s a rather negative version of that rule: I won’t care about you, and I don’t wish for you to care about me. Ayn Rand presented selfishness as a logical philosophy, and independence as a heroic way of life. Her followers believe that it’s possible to respect other people without actually caring about them or being interdependent with them — but they’re mistaken. When we don’t care about something, we see it as an object to be used. And although most people in our society see Ayn Rand for the

And although most people in our society see Ayn Rand for the  As I’ve already remarked, the habit of private property generates a philosophy of unconcern. Conversely, that philosophy justifies private property. Thus, the economy and psychology generate each other; I’ll refer to them both as separateness.

As I’ve already remarked, the habit of private property generates a philosophy of unconcern. Conversely, that philosophy justifies private property. Thus, the economy and psychology generate each other; I’ll refer to them both as separateness. Yahweh never answered Cain’s question, but I would answer yes, you should be your brother’s keeper, and he should be yours. Still, I am not advocating self-denial, self-sacrifice, self-crucifixion. You are a part of the global community, and you deserve comfort and happiness as much as anyone else does. I just want you to see that your comfort and happiness are not separate from everyone else’s.

Yahweh never answered Cain’s question, but I would answer yes, you should be your brother’s keeper, and he should be yours. Still, I am not advocating self-denial, self-sacrifice, self-crucifixion. You are a part of the global community, and you deserve comfort and happiness as much as anyone else does. I just want you to see that your comfort and happiness are not separate from everyone else’s. As your property is separate from mine, we must exchange things; we must have a market. But the market is not as it seems. A false mythology is perpetuated by

As your property is separate from mine, we must exchange things; we must have a market. But the market is not as it seems. A false mythology is perpetuated by  “People would quit working if we switched to guaranteed incomes; the economy would collapse.” – False, but with a qualification. People would quit if we switched to guaranteed incomes and no other changes were made. That’s because the jobs, presently structured to benefit the owners, are

“People would quit working if we switched to guaranteed incomes; the economy would collapse.” – False, but with a qualification. People would quit if we switched to guaranteed incomes and no other changes were made. That’s because the jobs, presently structured to benefit the owners, are  “The desire for personal gain is the source of all creativity and innovation, which makes the world a better place. Capitalism is smart, because it harnesses greed for the good of all.“– False. Bargaining with the devil is stupid, because it always ends badly; you’re the one who will end up in the harness, and not for the good of all.

“The desire for personal gain is the source of all creativity and innovation, which makes the world a better place. Capitalism is smart, because it harnesses greed for the good of all.“– False. Bargaining with the devil is stupid, because it always ends badly; you’re the one who will end up in the harness, and not for the good of all.

“Surely the problem is only in big businesses; there is nothing wrong with small businesses like the Mom-and-Pop grocery store on the corner, engaging in a bit of healthy competition.” – False. Capitalism grows like cancer. The Little Prince explained that every baobab must be weeded out while it is still small, or the resulting giant baobab would destroy his little planet. Even the Mom-and-Pop store perpetuates the idea of our separateness. Will Mom and Pop give free groceries to the man who just got laid off? That won’t be enough. What we need is not charity, but solidarity. Small businesses often do behave honorably, but that’s in spite of capitalism, not because of it. Their legitimacy is co-opted by big businesses, which then crush and swallow the small ones. And big and small can’t be separated, because they swim in the same sea of competition. And nearly all of our society has been persuaded that competition is good for us, but that’s the exact opposite of the truth; there is no such thing as “healthy competition.” I don’t even know where to begin on the subject of competition — it deserves an entire essay — so I’m just going to refer you to Alfie Kohn’s excellent hour-long lecture,

“Surely the problem is only in big businesses; there is nothing wrong with small businesses like the Mom-and-Pop grocery store on the corner, engaging in a bit of healthy competition.” – False. Capitalism grows like cancer. The Little Prince explained that every baobab must be weeded out while it is still small, or the resulting giant baobab would destroy his little planet. Even the Mom-and-Pop store perpetuates the idea of our separateness. Will Mom and Pop give free groceries to the man who just got laid off? That won’t be enough. What we need is not charity, but solidarity. Small businesses often do behave honorably, but that’s in spite of capitalism, not because of it. Their legitimacy is co-opted by big businesses, which then crush and swallow the small ones. And big and small can’t be separated, because they swim in the same sea of competition. And nearly all of our society has been persuaded that competition is good for us, but that’s the exact opposite of the truth; there is no such thing as “healthy competition.” I don’t even know where to begin on the subject of competition — it deserves an entire essay — so I’m just going to refer you to Alfie Kohn’s excellent hour-long lecture,  “Voluntary exchanges benefit everyone.” – False. The non-rich have few options, and must accept any deal that keeps them from starving; that’s why the so-called “volunteer army” is actually staffed by a “poverty draft.” And how many people would choose to be migrant farm-workers? But the rich have many options, and can choose just those that make them richer. Thus, every market transaction increases economic inequality, and concentrates wealth into fewer hands. Trickle-down economics doesn’t work — the market, growing ever more efficient, permits ever fewer crumbs to fall.

“Voluntary exchanges benefit everyone.” – False. The non-rich have few options, and must accept any deal that keeps them from starving; that’s why the so-called “volunteer army” is actually staffed by a “poverty draft.” And how many people would choose to be migrant farm-workers? But the rich have many options, and can choose just those that make them richer. Thus, every market transaction increases economic inequality, and concentrates wealth into fewer hands. Trickle-down economics doesn’t work — the market, growing ever more efficient, permits ever fewer crumbs to fall. I’ve already explained that the owners of our workplaces and our debts enrich themselves by exploiting the rest of us. A market economy inevitably concentrates wealth into few hands, like the board game of

I’ve already explained that the owners of our workplaces and our debts enrich themselves by exploiting the rest of us. A market economy inevitably concentrates wealth into few hands, like the board game of  After wealth becomes concentrated, it becomes self-perpetuating. Wealth rules, not primarily through secret cabals, but by buying the media, framing the issues, and distracting the public from what really matters. Wealth erodes through any government regulations, buying off both legislators and enforcers. Wealth writes loopholes for itself into the tax laws and all the other laws. Wealth twisted the USA’s 14th constitutional amendment into a justification for corporate personhood, and wealth may also twist into ineffectiveness the new amendment to end corporate personhood that is now being proposed by many reformists. Government and business

After wealth becomes concentrated, it becomes self-perpetuating. Wealth rules, not primarily through secret cabals, but by buying the media, framing the issues, and distracting the public from what really matters. Wealth erodes through any government regulations, buying off both legislators and enforcers. Wealth writes loopholes for itself into the tax laws and all the other laws. Wealth twisted the USA’s 14th constitutional amendment into a justification for corporate personhood, and wealth may also twist into ineffectiveness the new amendment to end corporate personhood that is now being proposed by many reformists. Government and business  Once profit has been enshrined as the ruling principle of society, it wreaks terrible destruction. Bipartisan

Once profit has been enshrined as the ruling principle of society, it wreaks terrible destruction. Bipartisan  After the revolution, maybe we’ll be able to restore the viability of the ecosystem. Maybe. But even then, we can’t return to some golden age of innocence. The growth of information is irreversible, unstoppable, and accelerating — that genie can’t be put back into the bottle — and its consequences will be far greater than most people realize. Information is not wisdom; information makes destructive technologies widely available. An authoritarian bully with drones is no deterrent for a suicidal madman employing germ warfare. Hobbes’s Leviathan can no longer maintain order and avert the “war of all against all.”

After the revolution, maybe we’ll be able to restore the viability of the ecosystem. Maybe. But even then, we can’t return to some golden age of innocence. The growth of information is irreversible, unstoppable, and accelerating — that genie can’t be put back into the bottle — and its consequences will be far greater than most people realize. Information is not wisdom; information makes destructive technologies widely available. An authoritarian bully with drones is no deterrent for a suicidal madman employing germ warfare. Hobbes’s Leviathan can no longer maintain order and avert the “war of all against all.” We can only be made safe by a caring culture that heals bullies and madmen, a universal family that leaves no one behind, so that no one wants to hurt others. We must create a culture that has never existed before. The transition to such a culture will be a humongous change, far bigger than anything that has been understood by the term “revolution”; it might be better described as

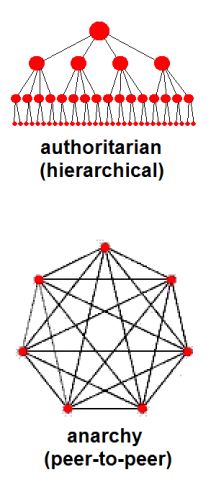

We can only be made safe by a caring culture that heals bullies and madmen, a universal family that leaves no one behind, so that no one wants to hurt others. We must create a culture that has never existed before. The transition to such a culture will be a humongous change, far bigger than anything that has been understood by the term “revolution”; it might be better described as  The alternative to hierarchical authority is anarchy — i.e., “no rulers.” Misleading propaganda associates the word “anarchy” with disorder and destruction — and, unfortunately, the Black Bloc has

The alternative to hierarchical authority is anarchy — i.e., “no rulers.” Misleading propaganda associates the word “anarchy” with disorder and destruction — and, unfortunately, the Black Bloc has  We must accept the reality that, at least initially, people speaking of new ideas will need great courage, for they will be beaten down violently. But police and soldiers remain human beings, despite all their training. They’ll join us when they realize they’ve been

We must accept the reality that, at least initially, people speaking of new ideas will need great courage, for they will be beaten down violently. But police and soldiers remain human beings, despite all their training. They’ll join us when they realize they’ve been