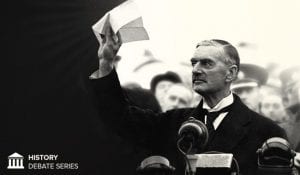

Understanding Lincoln: An interview with historian Allen Guelzo

Allen Guelzo is the Henry R. Luce III Professor of the Civil War Era at Gettysburg College, where he serves as director of the Civil War Era Studies Program. He is the author of numerous books, including Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President and Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America and Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Guelzo spoke with Tom Mackaman of the World Socialist Web Site in his office at Gettysburg College on a Saturday morning in March. A large academic conference was being held that weekend at the college entitled “The Future of Civil War History.” Gettysburg, in southeastern Pennsylvania, was the location of the bloodiest battle in the Civil War, and the city’s college is now one of the leading centers in the study of the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln.

Tom Mackaman: How did you come about your interest in Lincoln and the Civil War?

Allen Guelzo: I suppose the interest in Lincoln and the Civil War really is a long-term one that grows out of a certain boyhood interest and fascination with the man. But I didn’t really get deeply involved in Lincoln Studies until the mid-1990s. Because my PhD had been in the history of American philosophy, I was writing a book on the idea of freedom of the will and determinism in American thought. I knew that Lincoln had had some things to say on the subject, so I looked them up, ended up writing a paper about them, got invited to read it at the Abraham Lincoln Association meeting, and once my hand was in the Lincoln cookie jar I couldn’t get it out. A publisher approached me about writing a book on Lincoln. One thing led to another and, well, here I am.

TM: Which was the first book?

AG: Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, with a title borrowed shamelessly from Walt Whitman.

TM: You have been at work on Lincoln, the Civil War, and the emancipation of the slaves for a number of years now. How have your thoughts on these subjects evolved?

AG: Well, I don’t know actually that they have changed all that much. In general the outline that I have had in my mind of Lincoln as a character and a thinker has been pretty stable. And it really grows out of a moment in Charles Sellers’ book The Market Revolution in 1991, when, in describing the role of lawyers as the “shock troops of capitalism”, it struck me how very much Lincoln looked exactly like what Sellers was describing. That was reinforced when I read John Ashworth’s first volume on the capitalist transformation of America, and once again this description of the role of lawyers just seemed so remarkably close to Lincoln that it made me pursue this notion of Lincoln as your archetypal Whig, bourgeois, middle class cultural figure. And that in large measure is what I’ve been working from ever since.

TM: Could you explain what you mean by that a little bit more?

AG: Lincoln is, both culturally and in terms of his economic thinking, firmly and immovably located in the center of what we can call liberal democratic thought in the 19th century. He is very much market oriented, with tremendous confidence in the power of a capitalist society to transform for the better, and he believes in opening the possibilities of that society to as many as possible. To him, that’s what’s coterminous with liberty. If you have to put him in company, he would belong with John Stuart Mill, whom he seriously admired. Shortly before he was assassinated, Lincoln was asked by a journalist what books had been most influential for him. One of the two books he indicated is Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. Put him in that context of the upwardly aspiring bourgeoisie—that’s Lincoln.

Lincoln is someone who has fled from romantic agrarianism, the kind of agricultural subsistence economy that his father was a participant in and a good example of. Lincoln regarded that world with distaste and left it as soon as he turned 21. He never looks back, and moves at once into the world of the cash economy, cash wages, investment, and business, and that’s where he lives for the rest of his life. He fails twice actually at being in business, but undeterred by that he shifts over to becoming a lawyer, and that’s when he becomes part of the “shock troops of capitalism” that Sellers talks about.

TM: In his law practice he did extensive business with railroad concerns, did he not?

AG: That was his single most lucrative client. Lincoln’s law practice is a very extensive one, and it runs all the way from big railroad cases down to $2.50 trespass cases. But what is remarkable about his law practice is that it’s overwhelmingly a civil practice—only about 15 percent of his overall cases were criminal cases. And the preponderance of that civil practice was debt collection. He was, so to speak, a repo man. He was either collecting or enforcing collection. And he was a big friend of the railroads. He even served briefly as a lobbyist. If you’d asked anybody in central Illinois in the late 1850s who Abraham Lincoln was, they probably would have said, “Oh, that railroad lawyer.”

One aspect of that railroad practice stands out: in 1856, Lincoln wrote a very extensive memorandum about evicting squatters from railroad land. That was a hot-button issue, because the lands that the Illinois Central was constructed upon were originally federally owned public lands, and many of them had been squatted upon over the years by people who were firmly convinced that they possessed preemption rights. In other words, they believed they had the right of first refusal if the land was ever to be disposed of by the government. Lincoln’s memorandum pulls out all the legal floorboards from under them and authorizes the Illinois Central Railroad to proceed to eviction without any restraint.

TM: Lincoln was an attorney for the railroads. But in other contexts, in certain quotes, did he not privilege labor?

AG: He does indeed talk about labor having priority over capital, which many people mistake as a statement of the labor theory of value. But he’s actually not talking about any labor theory there. What he’s doing is objecting to a labor relationship that said that capital has to give orders to labor, that laborers are so ignorant and so stupid—and of course what he’s primarily talking about here are slave laborers—that the only way any kind of productive work will happen is if capital—meaning slave owners—gives them direction. That he objected to, because that impugned the agency of the self-motivated laborer in a capitalist economy. But it’s the agency of the laborer, not any imputation to the value of the laborers’ product, that Lincoln is describing.

He’s actually responding to James Henry Hammond’s famous “Mudsill” speech of 1858 which Lincoln thought was profoundly offensive for re-introducing the notion of status: status meaning that certain people were born a certain way, and they were always going to be that way, so the only way you’ll make them work is if you flog them. That was what Lincoln was objecting to.

TM: What do you make of the concept of the “free labor ideology,” a concept that is associated with the work of the historian Eric Foner?

AG: Foner wrote the book— Free Labor, Free Soil, Free Men —in 1970, based on his doctoral dissertation under Richard Hofstadter. And it’s a very, very, good book. In fact it’s hard to put a finger on a book that better explicates the free labor ideology of the Republicans—and of Lincoln in the bargain. Some close seconds to that are Heather Richardson’s The Greatest Nation of the Earth, which is not specifically about Lincoln but is about the broader free labor/free wage commitments of the Republicans, and a very good chapter on Lincoln in Daniel Walker Howe’s Political Culture of the American Whigs.

TM: Could you explain the way Lincoln’s career as an attorney in this period influenced his thinking on slavery?

AG: To Lincoln, slavery undercut the free labor outlook on the world because it denied advancement and self-improvement. For Lincoln, the great attraction of any economic regime was the degree to which it permitted accumulation and self-promotion. He once described the ideal system as being one where the penniless beginner starts out working for somebody else, accumulates capital on his own by dint of savings, goes into business for himself, and then eventually becomes so successful that he hires others, who in turn continue the cycle. And he spoke of that as being the order of things in a society of equals. For him, the very notion of equality is a matter of equality of openness, aspiration, and opportunity.

This is what he says in 1859 at the Wisconsin State Agricultural Fair (and bear in mind that he is saying this only a year after one of the most severe financial depressions in the 19th century):

Some of you will be successful, and such will need but little philosophy to take them home in cheerful spirits; others will be disappointed, and will be in a less happy mood. To such, let it be said, “Lay it not too much to heart.” Let them adopt the maxim, “Better luck next time”; and then, by renewed exertion, make that better luck for themselves.

The only reason people do not succeed in a capitalist environment is because they are improvident, they are lazy, they are good for nothing, or they experience some incredible turn of bad luck—that’s why “better luck next time.”

That may seem like vanishingly small consolation to people who’ve just come through a depression, but for Lincoln, that kind of hardship paled beside slavery. Slavery says that there is a category of people that can never be allowed to rise, that cannot improve themselves no matter how hard they try because they will always be slaves. It’s very much the classic disjuncture between the Enlightenment and feudalism. Feudalism talks about people being born with status, and everyone comes into this world equipped with astatus. This status is either free or slave, serf or nobility, elect or damned, whatever. For the Enlightenment people come into this world armed withrights, and the ideal political system is the system that allows them to realize those rights, to use those rights in the freest and most natural fashion possible.

TM: Is this what you have in mind when you refer to Lincoln as the last Enlightenment figure in American history?

AG: Exactly. This is why I call him our last Enlightenment politician. Or at least the last one who is securely and virtually exclusively located within that mentality.

TM: Lincoln once said that he did not have a political thought that did not flow—

AG: From the Declaration of Independence …

TM: … Could you talk about the relationship between Lincoln and the American Revolution, and Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence in particular?

AG: He loves—and he’s not exaggerating—the Declaration of Independence. When he talks at Gettysburg about the country being founded on a proposition, that’s what he means, and specifically that all men are created equal. What does he mean by equal though? He means equality of aspiration. He spoke those words about never having had a political thought which did not flow from the Declaration in February of 1861, outside Independence Hall. He believed that what the Founders meant, what the Declaration of Independence meant, was that everybody in the race of life ought to get a fair start and a fair chance. That was the star by which he navigated, and the best example he could offer to anybody was his own life.

TM: The rail splitter.

AG: Sure. Here’s someone who had come up from grinding backwoods poverty and by dint of his own effort, intelligence, and gifts, had risen to more than a modicum of success. Not only success in financial terms but success socially. In every respect he was his own confirmation of his theories. Anyone who impugned free labor and the free labor ideology was really attacking him personally.

TM: Considering further Lincoln’s own intellectual formation, much has been made of his facility with Shakespeare and the Old Testament. What other influences were there? Did he read Melville, did he read Hawthorne?

AG: Not likely. He had no taste for fiction. He said once that he tried to startIvanhoe but only got halfway through it—which may replicate the experience of many undergraduates and high school students today. But that in itself is something of a statement. He read precious little fiction. He loved poetry, though. But it was, significantly, not romantic poetry that he cottoned up to. He did like Byron, but the poets he admired the most were very much poets of the Enlightenment. He loved Pope and quoted him often from memory. He loved Burns, who is a transitional figure between the Enlightenment and romanticism.

In terms of other things that he reads, he reads political economy. He read most of the major treatises that flowed downstream from Adam Smith. He’s read McCulloch, Henry Carey, and Francis Wayland. One observer said that on political economy he was great, that there was no one better than Lincoln.

He also had some scientific interest in geology. John Hay, his secretary, was surprised to discover he had some interest in philology and the origins of language. He never explains why he is interested in those, but he would always surprise people by what he knew. One Canadian journalist who visited in him 1864 was taken aback when Lincoln launched into a long “dissertation” on comparative points of British and American law.

That’s particularly surprising because in another context Lincoln professed to know nothing about international law. But Lincoln habitually would tell people he was totally ignorant of a subject which in fact he was quite well versed in, because then they would underestimate him, and when they underestimated him they would fall into his trap. Leonard Swett once said that anybody who mistook Lincoln for a simple man would soon end up with his back in a ditch.

TM: The film Lincoln depicts this moment in which Lincoln makes a major decision by discussing Euclid’s principles of mathematics. Is there some basis to this in fact?

AG: Yes, he did read Euclid. It appealed to what one of his law partners referred to as Lincoln’s passion for “mathematical exactness.” Lincoln was not eloquent in the usual 19th century way, certainly not in the romantic way. He was not a man of frothing at the mouth or shaking his fist in a dramatic way. Lincoln was logic, and when he got the hook in your mouth he would pull you in no matter how much line was involved. One observer of the Lincoln-Douglas debates said that if you listened to Lincoln and Douglas for five minutes, you would go with Douglas. If you listened to them for an hour you always went with Lincoln.

I thought the film was 90 percent on the mark, which given the way Hollywood usually does history is saying something. I thought that it got with reasonable accuracy a lot of Lincoln’s character, the characters of the main protagonists, and the overall debate over the 13th Amendment. The acting and screenwriting were especially well done. I remember thinking afterwards that all the time I’d been watching the movie I had never thought that Daniel Day-Lewis was acting, because what he portrayed seemed so close to my own mental image of what Lincoln must have been like.

TM: Lincoln remains such a popular figure. What explains his hold on our fascination and our affection? If we were to consider him only as an attorney for the railroads, as a bourgeois politician, perhaps this would be difficult to explain?

AG: For several reasons. First, as a leader, he is a combination of the virtues of democratic leadership—as opposed to, say, aristocratic leadership, which honors valor, physical prowess, and dominance. Democratic leadership is more about perseverance, self-limitation, and humility. What we see in Lincoln is a collection of the virtues we think are most important in a democratic leadership.

Secondly, he really did preside successfully over this incredibly critical moment we call the Civil War. He did keep the union together, he did defeat the Confederacy. Anyone who sits down for a moment to think about what the alternative would have looked like—a successful breakaway Confederacy—and how that would have flowed downstream has to be with impressed with what Lincoln was able to save us from. There is in the end no intrinsic reason why the Southern Confederacy should not have achieved its independence. And if they had, that would have had serious implications for the later role the North American continent plays in world affairs. Imagine a North American continent as divided politically and economically as South America. This would take the United States off the table as a major world player, and then what would you do with the history of the 20th century?

But I think Lincoln is also important in a third way—and this may be of interest to your readers. I come back to the old Werner Sombart question—“Why there is no socialism in America?” There have been any number of answers. I wonder out loud whether one reason there is no socialism in America is because of Lincoln.

In the American context Lincoln imparted to liberal democracy a sense of nobility and purpose that it has not always had in other contexts. He makes democracy something transcendent, and especially at Gettysburg where he talks about the nation having this new birth of freedom. He ratchets the horizons of liberal democracy right up past the spires of Cologne Cathedral and he makes it this glowing attractive ideal that people are willing to make these tremendous sacrifices to protect. Because at the end of the day this is what the Civil War is about—it’s about the preservation of liberal democracy. In the 1860s the United States was the last Enlightenment experiment that was still standing. What you had in the climate of mid-19th century Europe was the renaissance of romantic aristocracy …

TM: He refers to this in the Gettysburg Address…

AG: Yes, that’s really what he’s talking about. This war is a test whether this nation or any other nation so conceived can long endure. Is democracy self-destructive? Are the aristocrats right? That the only way you’ll ever have order in society is to let them run things? That you cannot put rule into the hands of ordinary people because they’ll botch it from selfishness, egotism, and stupidity? The Civil War becomes this demonstrator model for aristocrats to say, “See what happens when you let ordinary people govern.” The romantic contempt of the American experiment, whether that contempt comes from a Heinrich Heine, from an Otto Von Bismarck…

TM: Or from the Southern elite…

AG: Exactly. This is what Lincoln saw in the Southern elite—a defection from Enlightenment bourgeois politics toward aristocratic rule. And I think there’s really some substance there. Because if you look at someone like Bismarck, for instance, the Prussian Junkers are not great aristocrats. They are the squirearchy. They are very similar in complexion and structure to the plantation aristocracy of the Old South. No surprise then that Bismarck sees in the Confederacy something that he admires, that he applauds. Lincoln saw himself arrayed against that.

Lincoln sees American democracy as a last stand, what he calls the last, best hope. And if this goes down, we may so discredit the whole notion of democracy that no one will ever want to go this way again, and so this is the test. It’s a test of whether or not we’ll have this new birth of freedom, if we’ll finally shuck off these last husks of aristocracy and move forward in the direction of democracy. That for him is the vital issue.

People today often want to separate slavery, and say that Lincoln was interested in preserving the union and not in destroying slavery. No, that gets it exactly wrong. The two are as knotted together as a rope, because the only union worth preserving is a union that has abjured slavery. So for Lincoln to get rid of slavery is to purge America of the aristocratic poison. He once said that slavery was the one retrograde institution that was poisoning the American republic, keeping the American republic from realizing its full potential.

TM: What do you make of the criticism of Lincoln the historical figure from the standpoint of identity politics, or, more recently, similar criticism over Lincolnthe film?

AG: There has been a current that wants to reject the image of Lincoln as the Emancipator by questioning whether or not he emancipated the slaves. It has had some long innings. Some of it goes back to Marx’s comment on the Gotha Program, that the proletariat has to emancipate itself, that it cannot look to some other agency to do so. That image of self-emancipation certainly has a role to play in W.E.B. Du Bois’ Black Reconstruction in 1930, because Du Bois will say we can’t really talk about emancipation unless it’s self-emancipation. Du Bois is picturing race as the replacement for class. And this gets popularized in the writing of people like Vincent Harding, Lerone Bennett, Barbara Field, and any number of people writing today—some of whom have probably never read Du Bois, much less Marx.

Lincoln does drop comments that can be taken out of their historical context. For instance the most widely cited statement about race is the one he makes at the fourth debate at Charleston, Illinois. He says:

I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races,—that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will for ever forbid the two races living together.

People like Bennett focus on this and say, Lincoln was really just another garden variety racist. What they do not see is what Lincoln follows that comment with. He says:

Herzl: No nice way to do serious ethnic cleansing. by WILLIAM JAMES MARTIN The ideology, or political project, of Zionism which underlies the creation of the State of Israel had, in fact, a Christian origin rather than a Jewish one, as writings can be found dating from the 1500’s, written by Christian clergymen in England advocating the migration of Jews to the Holy Land. The migration of Jews to Palestine was also advocated by Napoleon Bonaparte. The first Jewish presentations of Zionism were written by Moses Hess in 1862 and 20 years later by Leo Pinsker, both of the Russian Pale, with each writer advocated a separate state for Jews. Twentieth century Zionism was initiated by Theodore Herzl who, likewise, advocated a separate state for Jews in his book, Der Judenstaat, written in 1896. One year later he formed the World Zionist Congress which held its first meeting in Basel Switzerland in that same year. What to do with the Arabs present in the prospective Jewish state dominated the thoughts of the founders of Israel from Herzl up until the actual expulsion of the Palestinians in 1948. “[We shall] spirit the penniless population across the frontier by denying it employment. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.” Thus the concept of the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians was introduced. It is not rocket science, if you want to create a state exclusively of Jews, mostly European, in the heart of the Middle East, then you must first get rid of the Arabs. In 1928, Vladimir Jabotinsky, founder of the Revisionist wing of the Zionist movement, which advocated the revision of the British Mandate for Palestine, to include the east bank of the Jordan and some of present-day Egypt, Jordan and Syria, and which was the progenitor of the present-day Lukud party, wrote, of the Palestinians, in his booklet, The Iron Wall, that no people were ever willing to give up their land to another people through mutual agreement and that the colonization by European Jews of Palestine must be prosecuted by force and against the will of the indigenous people, and must be executed behind an iron wall of bayonets, using his metaphor. By the 1930′s, ‘transfer’ of the Arabs was the unanimous preference of the founders of Israel. So-called transfer committees, headed by Joseph Weitz, Director of Land Management for the Jewish Agency, were set up explicitly for the purpose of studying ways of ‘transferring’ the Arabs out of Palestine. At the beginning of 1948, despite 50 years of land purchases, Jews only owned 6% of the land of Palestine. By the year’s end, the Israeli army controlled 78% of Palestine in a process of ethnic cleansing that saw the destruction of 531 Arab towns or villages and 11 Arab urban areas, with massacres, large or small, at almost all of those towns or villages, the almost complete looting of Palestinian property and wealth, including looting of the banks, confiscation of Palestinian homes and property, businesses, fields and orchards. The Palestinian people lost everything. Those who survived the massacres lost their careers, their means of livelihood, only to find refuge in tent cities set up by the United Nations which were later to become squalid refugee camps of cinder block buildings dotted around the Middle East. By just checking the time line, one quickly disposes of the 60 year old Israeli propaganda myth that the pre-state of Israel was innocently minding its own business when it was attacked by five armies of surrounding Arab states. The ethnic cleansing of Palestinians began on November 30, 1947 in Haifa when the Jewish army under David Ben Gurion, along with the Jewish terrorist group, the Irgun, under Manachem Begin, began shelling the Arab sections of that city. The ethnic cleansing of the Arabs of Haifa was completed by April, 1948 when shelling by the Jewish forces forced Haifa’s Arab residents to flee toward the harbor where they attempted to board boats in order to escape. Thus the Arabs of Haifa were literally ‘pushed into the sea’ by the Jewish forces. Many of those fleeing were drowned when the boats were overloaded and capsized. In March of 1948, David Ben Gurion finalized and distributed Plan D to his officers, which was a program for destroying and depopulating Arab villages and eliminating any resistance. Already, by that date, already 30 Arab villages had been depopulated of Arabs. On revealing paragraph of this document states: The massacre at the Arab village of Deir Yassin, only one of many, but possibly the most famous, occurred on April 9, 1948. Israel declared itself a state on May 14, 1948, and it was the next day, May 15, that the first regular soldier of an Arab army set foot in Palestine. By then, about half of the 750,000 to 800,000 Palestinian refugees had been generated and all of Palestine’s urban centers and had been depopulated of Arabs. Let me be clear: the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians began six months before the entrance into Palestine of any regular member of the surrounding Arab armies. And further, the intent of the Zionist movement to displace the Arab population had been in place for half a century. One cannot understand the natural anger and resentment of the Arab people, and particularly the Palestinian people, toward Israel, and also to the West, for supporting their oppressors and for being blind to their own suffering, without coming to a full understanding of the catastrophe, which the Palestinian people call the Nakbah, that befell them in 1948. One cannot so understand if one accepts the lie that the pre-state of Israel was just innocently defending itself, which is the fiction which, I suspect, most members of the US Congress accept. Nor can one understand the futility of the exalted ‘peace process’, ongoing now for the last 24 years, concurrent with the further erosion of Palestinian rights and freedom, and migration of new Jewish settlers into the West Bank and East Jerusalem, without understanding that Israeli acquired its present status as a state, not by negotiation with Palestinians, but by brute force and very much against the will of the indigenous people. For the Arab people, Israel is an alien implant, imposed by western powers, in the heart of the Arab world against the will of the Arab people. The Palestinians living under occupation have been living in that situation for 45 years, deprived of basic human rights, abused and, more often than not, humiliated, suffering degradation and humiliation on a daily basis, as their land and property and resources are daily confiscated by the state of Israel, which also winks at settler violence and looks the other way as settlers, who have built their settlement on hilltops, dump their sewage onto Palestinian farmland, as they also cut down their olive trees, burn their fields and poison or otherwise kill their livestock, in order to make way for more settlers and settlements as well as to make life as miserable as possible for the Palestinians with the intention of make their migration from Palestine more attractive than their continuing presence. The Palestinian refugee population now stands at about 5 million – the largest refugee population in the world and the longest standing refugee population. There are no prospects on the horizon for any change in their situation. Zionism is a political program of clearing Palestine of Palestinian Arabs in order to create the space for an exclusive Jewish state. As such, its goal is to destroy the Palestinians as a people with an identity as a people and with an attachment to the land of their births and the births of their ancestry. Such a project meets the definition of genocide in international law. Genocide is a crime against humanity was well as against its immediate victims. Genocide is a crime in which all of humanity is degraded. When the US Congress gave 29 standing ovations to the Israeli Prime Minister, Mr Netanyahu, in his most recent appearance before this body, they were applauding a man whose has dedicated his entire life to the destruction of the Palestinian people and their ethnic cleansing. The US Congress does not seem to know, or to care: Those who came to Palestine in the 20th century for the purpose of ethnically cleansing the indigenous people in order to establish a racially or ethnically pure Jewish state are the victimizers, not the victims; those who are being ethnically cleansed are the victims, not the victimizers. The US Congress has it backwards. Did it not occur to the members of this august group that Mr Netanyahu, after receiving 29 standing ovations, would return to Israel with an imprimatur from the US Congress to continue, or even accelerate, the disenfranchise of the Palestinians? The day that the Knesset endorsed Oslo II by a majority of one, in 1993, thousands of demonstrators gathered in Zion Square in Jerusalem. While the demonstrators displayed an effigy of Rabin in SS uniform, Netanyahu delivered an inflammatory speech calling Oslo II a surrender agreement and accused Rabin of ‘causing national humiliation by accepting the dictates of the terrorist Arafat.’ A month later, on November 1995, Rabin was assassinated by a religious-nationalist Jewish fanatic with the explicit aim of derailing the peace process. Rabin’s demise, as his murderer expected, dealt a serious body blow to the entire peace process. (Shlaim – Israel and Palestine, Verso) There is a YouTube video, from 2002, of Mr Netanyahu seated on a couch in the home of an Israeli family, unwittingly on camera, and bragging that he was able to destroy Oslo, and that he deceived the US president at that time, Bill Clinton, into believing he was helping implement the Oslo accords by making minor withdrawals from the West Bank while actually entrenching the occupation. He boasts that he thereby destroyed the Oslo process. He dismisses the US as “easily moved to the right direction” and calls high levels of popular American support for Israel “absurd.” He also suggests that, far from being defensive, Israel’s harsh military repression of the Palestinian uprising, was designed chiefly to crush the Palestinian Authority led by Yasser Arafat so that it could be made more pliable for Israeli diktats. Mr Netanyahu is playing the US Congress for fools. Days before he received 29 standing ovations from the US Congress, Mr Netanyahu sat in the Oval Office with the American President and told him that he would not accept the ’67 borders as the basis of a solution. The ’67 borders as a basis for a settlement has been the consistent American position since the ’67 war, for 45 years, under both Democrat and Republican presidents. Mr Netanyahu told the American President that Israel needed most of the West Bank because otherwise Israel would be militarily vulnerable, and also, an indefinitely long presence in the Jordan Valley, also because otherwise Israel would be militarily vulnerable. And, of course, Mr Netanyahu has a consistent policy of ethnically cleansing Jerusalem of Palestinians because it was given to Jews by God, or because it is the Jewish birthright. That leaves very little for the Palestinians, does it not? The original inhabitants of Palestine, the Palestinians, were promised statehood by the British Mandate for Palestine. It is not true, BTW, that Jews were building the city of Jerusalem 3000 years ago, as Mr Netanyahu repeatedly claims, and even if it were, it would not override international law’s injunction against ethnic cleansing. The archeologists tell us that Jerusalem was an abandoned village 3000 years ago surrounded by a small agrarian population. This is during the purported time of David and Solomon and the purported United Kingdom. Jerusalem did not achieve any significance until the 8th century BCE and then as the continuous development of a Palestinian settlement from which artifacts have been discovered of representing a variety of Palestinians deities of which Yahweh was only one of several . There is not one shred of evidence for a Jewish temple dating from 3000 years ago, or any other significant engineering structures from that time. Furthermore, it is unlikely that Mr Netanyahu, or any other Israeli who claims to be derived from God’s Chosen, possesses any genetic connection to the ancient Judeans. The burden of proof is on Mr Netanyahu to produce a verifiable pedigree or genealogical tree stretching back 3000 years into the Iron Age. In fact, no living person is able to do that. Mr Netanyahu derives from European Jewish ancestry, who, in turn, derive mostly from the Russian Khazars, those living near the Volga and Don Rivers, who converted in mass to Judaism in the 9th century CE bringing a much larger population to Judaic belief than any population of Judeans of the ancient world, or their descendants. Paul Wexler, a philological archeologist at Tel Aviv University, in his book, The Non-Jewish Origin of the Sephardic Jews, writes that Hebrew and Aramaic made their appearance in European Jewish text only in the 10th century CE, and were not products of earlier linguistic developments. During the first millennium CE, Jewish believers in Europe knew no Hebrew or Aramaic. Only after the religious canonization of Arabic in Islam and Latin in Christianity, did Judaism adopt and propagate its own religious language as a high cultural code. It is as likely that Adolf Hitler is a descendant of the ancient Judeans as is Mr Netanyahu, for all anyone knows. The locus of the present day conflict in Palestine may not be in Palestine but in Washington, DC, and in the US Congress, because the US Congress supports, probably unwittingly for the most part, the ethnic cleansing and the destruction the Palestinian people. William James Martin has written many articles on the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Middle East.Zionism and the United States Congress

Thus Herzl stated:

In Praise of Emotion

It was a moving experience. Moments that spoke not only to the mind, but also – and foremost – to the heart.

Last Sunday, on the eve of Israel’s Remembrance Day for the fallen in our wars, I was invited to an event organized by the activist group Combatants for Peace and the Forum of Israeli and Palestinian Bereaved Parents.

The first surprise was that it took place at all. In the general atmosphere of discouragement of the Israeli peace camp after the recent elections, when almost no one dared even to mention the word peace, such an event was heartening.

The second surprise was its size. It took place in one of the biggest halls in the country, Hangar 10 in Tel-Aviv’s fair grounds. It holds more than 2000 seats. A quarter of an hour before the starting time, attendance was depressingly sparse. Half an hour later, it was choke full. (Whatever the many virtues of the peace camp, punctuality is not among them.)

The third surprise was the composition of the audience. There were quite a lot of white-haired old-timers, including myself, but the great majority was composed of young people, at least half of them young women. Energetic, matter-of-fact youngsters, very Israeli.

I felt as if I was in a relay race. My generation passing the baton on to the next. The race continues.

But the outstanding feature of the event was, of course, its content. Israelis and Palestinians were mourning together for their dead sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, victims of the conflict and wars, occupation and resistance (a.k.a. terror.)

An Arab villager spoke quietly of his daughter, killed by a soldier on her way to school. A Jewish mother spoke of her soldier son, killed in one of the wars. All in a subdued voice. Without pathos. Some spoke Hebrew, some Arabic.

They spoke of their first reaction after their loss, the feelings of hatred, the thirst for revenge. And then the slow change of heart. The understanding that the parents on the other side, the Enemy, felt exactly like them, that their loss, their mourning, their bereavement was exactly as their own.

For years now, bereaved parents of both sides have been meeting regularly to find solace in each other’s company. Among all the peace groups acting in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, they are, perhaps, the most heart-lifting.

It was not easy for the Arab partners to get to this meeting. At first, they were denied permission by the army to enter Israel. Gabi Lasky, the indomitable advocate of many peace groups (including Gush Shalom), had to threaten with an application to the Supreme Court, just to obtain a limited concession: 45 Palestinians from the West Bank were allowed to attend.

(It is a routine measure of the occupation: before every Jewish holiday the West Bank is completely cut off from Israel – except for the settlers, of course. This is how most Palestinians become acquainted with Jewish holidays.)

What was so special about the event was that the Israeli-Arab fraternization took place on a purely human level, without political speeches, without the slogans which have become, frankly, a bit stale.

For two hours, we were all engulfed by human emotions, by a profound feeling for each other. And it felt good.

I am writing this to make a point that I feel very strongly about: the importance of emotions in the struggle for peace.

I am not a very emotional person myself. But I am acutely conscious of the place of emotions in the political struggle. I am proud of having coined the phrase “In politics, it is irrational to ignore the irrational.” Or, if you prefer, “in politics, it is rational to accept the irrational.”

This is a major weakness of the Israeli peace movement. It is exceedingly rational – indeed, perhaps too rational. We can easily prove that Israel needs peace, that without peace we are doomed to become an apartheid state, if not worse.

All over the world, leftists are more sober than rightists. When the leftists are propounding a logical argument for peace, reconciliation with former enemies, social equality and help for the disadvantaged, the rightists answer with a volley of emotional and irrational slogans.

But masses of people are not moved by logic. They are moved by their feelings.

One expression of feelings – and a generator of feelings – is the language of songs. One can gauge the intensity of a movement by its melodies. Who can imagine the marches of Martin Luther King without “We shall overcome”? Who can think about the Irish struggle without its many beautiful songs? Or the October revolution without its host of rousing melodies?

The Israeli peace movement has produced one single song: a sad appeal of the dead to the living. Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated within minutes of singing it, its blood-stained text found on his body. But all the many writers and composers of the peace movement have not produced one single rousing anthem – while the hate-mongers can draw on a wealth of religious and nationalist hymns.

It is said that one does not have to like one’s adversary in order to make peace with them. One makes peace with the enemy, as we all have declaimed hundreds of times. The enemy is the person you hate.

I have never quite believed in that, and the older I get, the less I do.

True, one cannot expect millions of people on both sides to love each other. But the core of peace-makers, the pioneers, cannot fulfill their tasks if there is not an element of mutual sympathy between them.

A certain type of Israeli peace activist does not accept this truism. Sometimes one has the feeling that they truly want peace – but not really with the Arabs. They love peace, because they love themselves. They stand before a mirror and tell themselves: Look how wonderful I am! How humane! How moral!

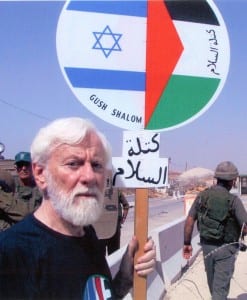

I remember how much animosity I aroused in certain progressive circles when I created our peace symbol: the crossed flags of Israel and Palestine. When one of us raised this emblem at a Peace Now demonstration in the late eighties, it caused a scandal. He was rudely asked to leave, and the movement publicly apologized.

To give an impetus to a real peace movement, you have to imbue it with the spirit of empathy for the other side. You must have a feeling for their humanity, their culture, their narrative, their aspirations, their fears, their hopes. And that applies, of course, to both sides.

Nothing can be more damaging to the chances of peace than the activity of fanatical pro-Israelis and pro-Palestinians abroad, who think that they are helping their preferred side by demonizing the other. You don’t make peace with demons.

Fraternization between Palestinians and Israelis is a must. No peace movement can succeed without it.

And here we came to a painful paradox: the more this fraternization is needed, the less there is.

During the last few years, there has been a growing estrangement between the two sides. Yasser Arafat was very conscious of the need for contact, and did much to further it. (I constantly urged him to do more.) Since his death, this effort has receded.

On the Israeli side, peace efforts have become less and less popular. Fraternization takes place every week in Bil’in and on many other battlefields, but the major peace organizations are not too eager to meet.

On the Palestinian side there is a lot of resentment, a (justified) feeling that the Israeli peace movement has not delivered. Worse, that joint public meetings could be considered by the Palestinian masses as a form of “normalization” with Israel, something like collaboration with the enemy.

This must be changed. Only large-scale, public and heart-felt cooperation between the peace movements of the two sides can convince the public – on both sides – that peace is possible.

These thoughts were running through my head as I listened to the simple words of Palestinians and Israelis in that big remembrance meeting.

It was all there: the spirit, the emotion, the empathy, the cooperation.

It was a human moment. That’s how it all starts.

URI AVNERY is a legendary peace activist and onetime hero soldier in the wars that created the state of Israel. He is the real life Jewish fighter who Leon Uris used as inspiration for the novel (and later blockbuster film) EXODUS’ Ari Ben Canaan, played by Paul Newman.

Pathology and Reconciliation on the Korean Peninsula

My introduction to Korean films and the changing political landscape in the south was Lee Chang-dong’s 2000 masterpiece “Peppermint Candy”. Not only was it a fearless assault on South Korean repression of strikes and student protests in the 1980s, it was my pick for best narrative film that year leaving Academy Award winner “Gladiator” in the dust. If Hong Kong cinema had become increasingly formulaic by then, South Korea picked up the slack and turned into by far the most fertile ground for new cinema in the world.

Chang-dong Lee went on to write and direct other masterpieces, including “Mother” and “Poetry”, but even more importantly to serve as a symbol of progress in the south and reconciliation with the north in his capacity as Minister of Culture and Tourism in 2003-2004 under reformer President Roh Moo-hyun. Roh continued the policies of Kim Dae-jung who ruled from 1998 to 2003. Widely regarded as the Nelson Mandela of South Korea, Kim instituted the “Sunshine Policy” that sought to bring the two halves of the country closer together.

Roh’s presidency was marred by personal corruption and a willingness to make concessions to neoliberalism, especially the Free Trade Agreement with the U.S. in 2007. Despite this, Roh remained committed to rapprochement with the north. In 2011 Wikileaks released an American diplomatic cable to South Korea calling attention to Roh’s concerns over the mistreatment of North Korea.

Economic stagnation under Roh led to him being ousted in 2007 by Lee Myung-bak, the CEO of Hyundai, one of South Korea’s top chaebols. One year into his presidency, Lee trashed the Sunshine Policy and warned the north that he would end economic cooperation unless it abandoned its nuclear weapons program. Elected in 2012, South Korea’s first female president Park Geun-hye has been following Lee’s policies to the letter–hence the current crisis.

When I first got the idea of surveying South Korean films about the Korean War about two years ago, I had no idea that the review would coincide with the current stand-off although a Las Vegas bookie would have probably given me 50-50 odds given the bellicose posture of the last two presidents, egged on by the Obama administration.

Inspired by the Sunshine Policy, Korean filmmakers made an eye-opening series of films about the Korean War that shared Lee Chang-dong’s revisionist outlook. All rejected the hardline anti-Communism that prevailed from the 1950s through the 1980s, with some achieving the mastery of “Peppermint Candy”. For cinephiles and those wanting to gain an understanding of how Korean artists view their daunting situation, these films are essential.

Two of the films predate the Sunshine Policy but were fruits of a liberalization that actually began in the 1980s under President Roh Tae-woo. He may have not been willing to open up the system to workers and students but he did end film censorship. Those screenwriters and directors who decided to take advantage of the openings constituted a New Wave. Not only would it be easier for South Korean filmmakers to absorb Western culture; the film industry could now export its films to markets that had already been eager for the next John Woo flick. This, of course, is globalization at its best.

It is worth noting that Korean filmmakers continue to lament the Korean War and its aftermath even though the Sunshine Policy has ended. The 2011 “The Front Line”, the final film in my survey, is about as bitter a commentary as can be imagined. That being said, it must be understood that none dare to go as far as to make North Korea’s case. All of them express a liberal belief in the need for peace and reconciliation, which given the current impasse would be a big improvement.

The other revelation is that some of the films recognize that the south was not some kind of bastion of free market ideology when the Korean War broke out. As Bruce Cumings pointed out in his indispensible and recently published “The Korea War: a History”, the war was rooted in a decades long struggle against landlordism and Japanese occupation. (Cumings’s book is dedicated to Kim Dae Jung.)

Except where noted, all of these films are available from Netflix or Amazon.

1. Nambugun: North Korean Partisan in South Korea (1990)

Jeong Ji-yeong, a fierce opponent of censorship in his country and the Free Trade Agreement, was the director. Based on the memoir of a revolutionary journalist from the north named Tae Lee, it describes the bloody confrontations between radical-minded irregulars from the south and far more powerful imperialist forces on the battle fields of Mount Jiri. Jeong sparked controversy for making his communist characters so sympathetic. Among all the films under survey here, you will find no portrayal as fair-minded even though the characters are often given stilted “revolutionary” dialog to work with.

Cumings points to the war reporting of Walter Sullivan, a NY Timesman who defied the cold war consensus to explain what led the partisans to risk their lives in what amounted to an unwinnable battle. (Sullivan would become famous for his science reporting but started out as a war correspondent.) He described a “great divergence of wealth” that condemned middle and poor peasants to live a “marginal existence”. Cumings writes:

He [Sullivan] interviewed ten peasant families; none owned all their own land, and most were tenants. The landlord took 30 percent of tenant produce, but additional exactions—government taxes, and various “contributions”—ranged from 48 to 70 percent of the annual crop.” The primary cause of the South Korean insurgency was the ancient curse of average Koreans—the social inequity of land relations and the huge gap between a tiny elite of the rich and the vast majority of the poor.

Nambugun is available from Han Books for $19.75 and is well worth it.http://www.hanbooks.com/painsokoanok.html Be forewarned, however, that it is only available as a Region 3 DVD.

2. The Taebaek Mountains (1994)

Director Im Kwon-taek was an important member of Korea’s New Wave. The film is a dramatization of an uprising against landlords in the southernmost region of South Korea in 1948. While by no means sympathetic to the rebels, its portrait of the anti-Communist gangs and military is scathing. Im generally regards the peasants as innocent victims of rival forces bent on imposing rigid ideologies.

In David E. James and Kyung-Hyun Kim’s collection of essays titled “Im Kwon-taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema”, film professor Kyung Hyun Kim of U.C. Irvine who I had the good fortune to hear lecture on North Korean film a few years ago, makes some interesting points about “The Taebaek Mountains”. Unlike the conventional anti-Communist movies of the Cold War, the film emphasizes the tensions among the local populace in the south: “As Kim Pom-u, the protagonist of ‘The Taebaek Mountains’, asserts, the concentration of land ownership in the hands of a few landlords who had collaborated with the Japanese was one of the principle causes of he war”.

Bruce Cumings explains why the Japanese and then the American connection remains a sore point after all these years:

Kim II Sung began fighting the Japanese in Manchuria in the spring of 1932, and his heirs trace everything back to this distant beginning. After every other characteristic attached to this regime—Communist, nationalist, rogue state, evil enemy—it was first of all, and above all else, an anti-Japanese entity. A state narrative runs from the early days of anti-Japanese insurgency down to the present, and it is drummed into the brains of everyone in the country by an elderly elite that believes anyone younger than they cannot possibly know what it meant to fight Japan in the 1930s or the United States in the 1950s (allied with Japan and utilizing bases all over Japan)—and, more or less, ever since. When you combine deeply ingrained Confucian patriarchy and filial piety with people who have been sentient adults more or less since the Korean War began in 1950, you have some sense of why North Korea has changed so little at top levels in recent decades, and why it is highly unlikely to change radically before this elite—and its relentlessly nationalist ideology—leaves the scene.

“The Taebaek Mountains is also available from Han Books for $19.93 as an “all regions” DVD. http://www.hanbooks.com/tamor.html

3. Joint Security Area (2000)

Director Park Chan-Wook is best known for his “Vengeance Trilogy” that includes the 2003 “Oldboy”. While the trilogy is exciting grand guignol cinema, it seems strikingly distinct from the concerns of “Joint Security Area”, a film about the fraternization of southern and northern troops near the DMZ. But upon deeper reflection, isn’t the blind fury directed at the north a symptom of the same irrationality?

Although nominally a war movie, “Joint Security Area” might be more accurately described as a peace movie. When southern soldiers accidentally stray across the DMZ, their “enemies” rescue them from a land mine studded field. This leads to a male bonding that culminates in friendly card games, boozing, and practical jokes at the barracks in the south. Without giving away too much, the contradictions of two opposing social systems leads to a tragic conclusion.

A year after its release, “Joint Security Area” became the highest-grossing film in Korean history. Wikipedia reports that director Quentin Tarantino named the film as one of his twenty favorite films and that Roh Moo-hyun presented a DVD of the movie to Kim Jong-Il at a summit meeting in October 2007.

Park Chan-Wook made a Hollywood movie this year called “Stoker” that has been described as Hitchcockian. One hopes that tinseltown will not erode his creativity as it has with other immigrant directors including John Woo who has wisely made the decision to return to Asia.

“Joint Security Area” is available as a Netflix DVD.

4. Tae Guk Gi: The Brotherhood of War (2004)

This is my personal favorite. Director Kang Je-gyu is best known for “Shiri”, a blockbuster about a female spy from the north married to a South Korean CIA agent unaware of her true identity.

The brotherhood in the title refers to two brothers who end up on opposing sides during the Korean War. In keeping with the liberal and pacifist character of all the films, the war is seen as the tragic and necessary outcome of clashing fanaticisms. Kang is a superb director of battle scenes and was clearly influenced by Spielberg’s “Saving Private Ryan”.

However, what makes this film stand out is its no-holds-barred portrayal of the anti-Communist militias of the south that functioned as death squads. If both sides in the Korean War are considered as inimical to the broader interests of the Korean people, the fascist-like killers in the south are in a class by themselves. Needless to say, 20 years earlier in Korean history it would have been impossible to target one of the bastions of capitalist rule in the south.

Bruce Cumings describes the activities of the Northwest Youth Corps, a model for the group that figures in “Tae Guk Gi”:

As I was getting to know the furious and unremittingly vicious conflicts that have wracked divided Korea, I sat in the Hoover Institution library reading through a magazine issued by the Northwest Youth Corps in the late 1940s. On its cover were cartoons of Communists disemboweling pregnant women, running bayonets through little kids, burning down people’s homes, smashing open the brains of opponents. As it happened, this was their political practice. In Hagui village, for example, right-wing youths captured a pregnant twenty-one-year-old woman named Mun, whose husband was allegedly an insurgent, dragged her from her home, and stabbed her thirteen times with spears, causing her to abort. She was left to die with her baby half-delivered. Other women were serially raped, often in front of villagers, and then blown up with a grenade in the vagina.’ This pathology, perhaps, has something to do with the self-hatred of individuals who did Japanese bidding, now operating on behalf of another foreign power, and with extremes of misogyny in Korea’s patriarchal society.

“Tae Guk Gi: The Brotherhood of War” is available as a Netflix DVD.

5. Welcome to Dongmakgol (2005)

Unlike all the other films being surveyed, this is a comedy in the spirit of Philippe De Broca’s “King of Hearts”. Dongmakgol is a tiny and remote farming village in the south that not only has no idea that a war is taking place, but also has never seen a gun before.

When soldiers from the opposed sides end up in the village, they have a standoff that would likely lead to the kind of carnage happening everywhere else in the nation. When a grenade is tossed accidentally into their communal grain house, the explosion produces a surreal downpour of popcorn—just one of the comical touches in the film.

Feeling remorse for leaving the villagers without food, the soldiers decide to lay down their arms and help them make it through the winter. Obviously the film is a plea for Koreans to overcome their differences and work together for the greater good.

“Welcome to Dongmakgol” can be seen on Netflix streaming.

6. The Front Line (2012)

This is similar in spirit to “Joint Security Area”. Set during the final months of the war, soldiers from either side have not only grown war-weary; they have gotten into the habit of dropping off gifts to each other-like wine and cigarettes-at a designated secret store-box at the bottom of a bunker near the front lines.

Despite their desire to fraternize and to eventually live in peace, orders from on high force them to die in a senseless battle that takes place after a truce has been declared.

This is the second reconciliation film directed by Jang Hoon. His “Secret Reunion”, a 2010 film I have not seen, is about former north and south Korean spies bonding together out of a shared interest.

“The Front Line” is available in Netflix streaming.

It is difficult to get a sense of the feelings of ordinary South Koreans about the current crisis since the bourgeois media is so focused on the statements of various government officials. It is not hard to imagine that the pacifist feelings expressed in these six films continues to be felt by those Koreans who are tired of conflict and disunity—the likely overwhelming majority of its citizens.

Let’s allow Bruce Cumings have the parting words on this:

Thus we arrive at our absurd predicament, where the party of memory remains concentrated on its main task, perfecting a world-historical garrison state that will do its bidding and hold off the enemy, and the party of forgetting and never-knowing pays sporadic attention only when it must, when the North seizes a spy ship or cuts down a poplar tree or blows off an A-bomb or sends a rocket into the heavens. Then the media waters part, we behold the evil enemy in Pyongyang—drums beat, sabers rattle—but nothing really happens, and the waters close over until the next time. We don’t approve of them but pay little attention and pat ourselves on the back, while they mimic Plato’s Republic or monolithic Catholicism or Stalin’s cadres: they engineer the souls of their people from on high, starting at the beginning just as their neo-Confucian forebears did, when a human being is all innocence and wonder, and continuing until they have at least the image if not the reality of perfect agreement and coherence, a “monolithicism” (their term) seeking a one-for-all great integral that will smite the enemy. They think they know good and evil in their bones, but we aren’t so sure.

Louis Proyect blogs at http://louisproyect.wordpress.com and is the moderator of the Marxism mailing list. In his spare time, he reviews films for CounterPunch.