Russia and America, One Hundred Years Face to Face

//

=By= Gaither Stewart (rome)

Source: namu wiki

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s Stephen Lendman reported recently on these pages, Sergey Lavrov, Russia’s Foreign Minister and a unique political figure of today’s world, wrote in a March 3 essay in Global Affairs magazine that his country stands “at the crossroads of key trends” in the field of international relations and underlined that Russia, has “a special role in European and global history.”

Unfortunately, average citizens of the West, especially of the USA, know little and understand less of Russia’s history. To the great majority of Westerners, Russia is a mysterious and forbidding land somewhere in the East which poses a threat to the world which it aims at dominating. Therefore, I have summarized here some aspects of that long history in order to amplify and elucidate Russia’s possible role in the “difficult period of international relations”, of which Lavrov speaks so clearly and rationally.

The history of Russia has been marked, on the one hand, by constantly recurring patterns of fascination for and attraction to the West, and on the other hand abhorrence of and isolation from the same West to which Russia throughout its long history has often wanted to belong. To a certain degree Russia is different. Most Russians themselves are convinced of certain “particular Russian qualities” differentiating them from Western man—qualities not understood, and on the contrary, oftentimes misunderstood by the West. These characteristics can be described as components of a great messianic spirit: the Russian people have often believed themselves destined to be the salvation of the world.

While the few periods of wide contacts with the West have renewed the country, given it new vigor and skills and broken a chain of reaction tyranny, those purely Russian characteristics—tenacity, endurance, spiritualism, ethnic unity, love for mankind and popular traditions have given the country superhuman strength in periods of crisis. Russians never give up. Resistance is in the national DNA. Russians consider themselves invincible as a nation of which there are many examples: the battles of Moscow, Leningrad, Stalingrad.

Since early Muscovy, even after Ivan the Great in the 15th century who had defeated the Mongol occupiers of Russia, tripled Russia’s territory and making it a major European nation, and exchanged ambassadors and traders with the outside world, contact between Russians and foreigners was discouraged if not forbidden because they were considered contaminating even for the Tsar himself. And consequently secluded in special residential areas of Moscow.

While this great nation was being born, persecuted Europeans, adventurers and criminals were making their way to today’s USA, where they built log cabins and began the exterminations of the native peoples they encountered.

In comparison, sixteenth century Russia under Tsar Ivan the Terrible had become a formidable European power. It expanded its borders to the South but was defeated in its effort to conquer the Baltic States to the West. Those defeats in the West served to emphasize the necessity to modernize the Russian state. Ivan’s severe reforms and the methods employed to achieve them divided the country and sent many Russians in flight to the borderlands and beyond, joining the free-living Cossacks in the steppes.

Keep in mind that centuries were passing. And Russia was advancing, having liberated itself from the yoke of Tartar occupiers. Europeans and more and more Russians themselves understood that they were a great power to be reckoned with. The expanses, the realization of the great wealth their lands contain, the nation’s potential power, and importantly a unifying worldview (mirovozreniye) began welding the Russians together as a nation state.

It fell to Peter the Great (17th and early 18th centuries) to effect a “window on Europe”. Numerous Russians of all classes were sent abroad to learn necessary skills for Russia’s affirmation as a modern European nation, permitting Peter to build his new capital of Saint Petersburg on the Baltic Sea facing the West. Russians became cognizant of a new way of life and perceived new approaches to social living, shaking Russia out of its self-imposed isolation while the huge country also shook off any remaining inferiority complex vis-à-vis the West. By the end of Peter’s reign in 1725, the upper classes had indeed moved toward Europe, adopting European manners and dress and snobbishly preferring to speak French in the salons and the Court. The masses, the Russian people, a spiritual people, however, remained fixed and committed to old Russian traditions and the Orthodox religion.

As the 18th century progressed and while what became the USA was still a British colony, Catherine the Great imported ideas of French enlightenment—ideas however not yet compatible with traditional Russian views. She came to realize that the thinking of Voltaire and Rousseau were dangerous, a danger to herself … and a threat to Tsardom as well. This was long the great historical dilemma for the rulers of Russia: the nation’s need of Western knowhow in order to maintain its position as a world power and the concomitant threats these new influences posed to the system. In any case, by the end of the century the upper classes had learned a new way of life while they also came to recognize their own backwardness.

But the masses continued to toil and repeat generation after generation the old way of life. Such was the setting for the blossoming of Russian intellectual and social thought in the 19th century.

The French invasion of 1812 and Russia’s subsequent victory over Napoleon’s armies and the occupation of Paris changed Russian life.

For the first time in its history great numbers of ordinary Russians—as opposed to the privileged classes of the previous century—had close contact with one of the major centers of Western civilization. Young, educated military officers brought back from France new customs; but more important were the new ideas which fascinated and enraptured Russian intellectuals. In the face of the veritable explosion of these Western ideas, Alexander I was forced to renege on the promises of the liberalism of his youth. A new period of repression began. Nevertheless, the mild movement for a Constitution by some of the guards officers, the so-called, “Decembrists” of 1825, were crushed by the Tsar. Yet it was too late. Things had changed in Russia. The gentry and other educated classes were infected and began to resist the closed society.

The clash between autocracy in need of modernization but aware that those same ideas endangered its existence and the more enlightened educated classes no longer capable of living in darkness gave birth to the first Russian political emigration: intellectuals who left their homeland to fight for their ideals. The conservatives at home, horrified at how far they had moved away from old Russian traditions by becoming nearly Europeans began resisting European influences, thus articulating a struggle between themselves—the so-called Slavophiles—and the Westernizers. All the while the masses were silent.

In the 1830s and 40s, many liberal-minded men in Russia, suffocated by oppression because of their new ideas, by censorship and political backwardness, emigrated to Europe to study and struggle for fundamental freedoms for their people. The earliest émigrés went to France, England and Switzerland where they supported a program for a Constitution and reforms.

With the birth of Socialism in Europe, Russian socialists were soon born among these intellectuals. The departure of Alexander Herzen from Moscow to Europe in 1847 marked the beginning of a new era of Russian social-political thought which was to result in the overthrow of Tsardom and the Bolshevik victory over its more moderate opponents contesting for power in Russia.

The crushing of the Decembrists of 1825, the execution and exile of their leaders, and simultaneously the new ideas advanced by young liberals had made a great impression on Herzen who dedicated his life work to the cause of Russia democracy. Herzen symbolized the move of Russian émigrés from thought to action. Herzen and friends and later the anarchist, Mikhail Bakunin, initiated a movement centered around their political journal, The Bell, a movement democratic in nature, promoting a union between the governed and the governing in Russia and encouraging Russians in the homeland to overthrow autocracy. The Bell, published in London, circulated among intellectuals in the homeland, and allegedly read by the Tsar himself, was born on the wave of revolution raging across Europe and survived to introduce the revolutionary current of Lenin, Russian socialists and the later Bolsheviks.

During this period occurred the Mexican-American War (1846-47), in which Mexico lost half of its national territory to the Yankees, a war which became the model of American imperialistic wars, ultimately becoming world-wide, in Latin American, Asia, Europe and Africa. The war against Mexico was soon followed by the American Civil War, 1861-65, at the price of 600,000 dead in the name of US capitalism. Two new world powers, Russia in the East and the Unites States in the West were emerging, powers which that within a century would submerge the old European nation states.

Herzen, however, did not have the stuff that revolutionaries are made of. He had attacked Tsardom with the written word while in that period of crisis only extremes counted. Thus, Herzen inevitably fell from favor among younger, revolutionary émigrés. The struggles between the right and the left among Russian intellectuals left Herzen behind as an anachronism. Intellectuals meanwhile split over the concept of revolution—the moderates for whom some form of constitutional democracy was the goal moved toward the conservatives while the more liberal passed to the side of the revolutionaries. The next wave of Russian émigrés was to be dominated by the revolutionaries headed by Lenin.

Russia’s revolutionaries were a fiery bunch, as divided and factious as the Western left today. Russian revolutionaries disagreed, fought and split, and regrouped. But the movement was carried implacably forward by the organized hard core of the movement led by Vladimir Lenin. In essence, the various currents among Russian revolutionaries continued to reflect the old dispute between Westernizers and more traditional Slavophiles, a modern Western socio-political philosophy or the old Russian traditions, which are still the two deep souls of Russia. In this case, Russian Marxists, European in outlook, looked toward the new proletariat as their base. The Socialist Revolutionary wing counted instead on the peasants and, in a broad sense, the Russian people. The necessary support of both these currents was harnessed by Lenin and his successors after they won the revolution and the Civil War.

The Russian Civil War which erupted after the Bolsheviks took power in 1917 was marked by Western intervention (British, American, French and Japanese) on the side of the anti-revolutionary “Whites”. Since then Russian-American relations, despite alliances during European wars and various commercial agreements, have been based on American Capitalism’s unrelenting opposition to Socialism/Communism. Moreover, I believe there is also an underlying anti-Russian spirit present, perhaps because of American jealousy of Russia’s expanses and wealth, or ,even something more spiritual. The Cold War is most exemplary of America’s fundamental attitude, not only toward Russian Communism but also toward Russia itself.

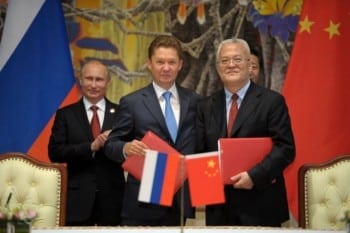

It is paradoxical that the eyes of the two new nations among world powers, Russia and the USA, still antagonistic toward each other after a century of seeing each other’s reflection in Europe, today are both looking eastwards. Despite the US encirclement of Russia and its goal of regime change and dismemberment of its old enemy, despite the proxy wars in Syria, despite America’s return to Latin America and the expansion of its presence in Africa, nothing can be more threatening to the USA than the terrifying image of the Russian-Chinese alliance. Lavrov’s words of Russia and a crossroads should scare the Jesus out of Washington.

Senior Editor Gaither Stewart, based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

Senior Editor Gaither Stewart, based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

Note to Commenters

Due to severe hacking attacks in the recent past that brought our site down for up to 11 days with considerable loss of circulation, we exercise extreme caution in the comments we publish, as the comment box has been one of the main arteries to inject malicious code. Because of that comments may not appear immediately, but rest assured that if you are a legitimate commenter your opinion will be published within 24 hours. If your comment fails to appear, and you wish to reach us directly, send us a mail at: editor@greanvillepost.com

We apologize for this inconvenience.

Nauseated by the

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

Send a donation to

The Greanville Post–or

But be sure to support YOUR media.

If you don’t, who will?

Contributing Editor, Murray Polner wrote “

Contributing Editor, Murray Polner wrote “