Dispatches from

Dispatches from

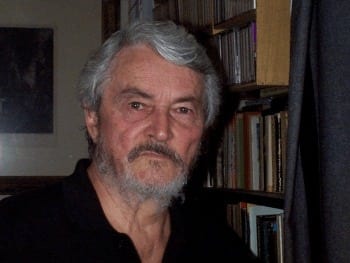

GAITHER STEWART

European Correspondent • Rome

AN INSTALLATION BY GAITHER STEWART

The massive exodus of peoples from Africa, the Middle East and parts of Asia to Europe as a result of worldwide American-inspired hegemonic wars has catapulted the sub-continent of Europe into ethnic, economic and moral chaos. While Europe tries to cope with millions of refugees and asylum seekers knocking on its doors, the United States and its fundamentalist allies force more peoples to flee because of their present wars in the Middle East against Syria and Iraq, with Iran and Russia in their sights, and China and the world at large in America’s mad vision. The outcome of today’s battles will reshape Europe geographically, demographically and morally as a result of the on-going hybrid struggle for geopolitical universal control by the USA and security for many peoples of the world.

MULTICULTURALISM

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]ulticulturalism is defined as the phenomenon of multiple groups of cultures living together within one society, as the result of the arrival of immigrants, or the acceptance and advocation of this phenomenon. Supporters of multiculturalism believe that different traditions and cultures can live together and enrich society; however, today, the concept is under fire to the point where the term “multiculturalism” is used more by critics than by supporters.

Multiculturalism as such occurs when a society accepts the culture of immigrants who, ideally, should also accept the culture of the land to which they have come. In general we refer here to the multiculturalism which is endorsed and actively encouraged by the government, thus becoming a sort of “state multiculturalism”. A society transformed by mass immigration into a society that is less insular, more vibrant and more cosmopolitan, is positive. However, the positive becomes negative and unmanageable when state (political) multiculturalism aims at managing diversity by ghettoization, putting people into ethnic boxes and defining their needs and rights by virtue of their boxes. At that point, the story changes.

Critics claim that multiculturalism promotes a tolerance of moral relativism and results in a loss of national identity. There is also the unfortunate reality that some cultures simply don’t mix, and multiculturalism sometimes leads to the development of embittered outsider subcultures. Multiculturalism is paradoxical in that it is itself a cultural value, especially to Western culture, while many cultures are in practice intolerant of other cultures.

A key debate in European social policy is that between multiculturalism and assimilationism … the melting pot idea. French ‘assimilationist’ policies are generally seen as the polar opposite of British-style multiculturalism. French leaders pride themselves in having rejected the divisive consequences of multiculturalism. Unlike in the rest of Europe, they insist, in France every individual is treated as a citizen, not as a member of a particular racial or cultural group, which is a patently false claim, demonstrated by the violent uprisings of subcultures in the northern periphery of Paris.

These youth are sometimes referred to as “the forgotten ones.” (Paris)

Thirty years ago, many Europeans saw multiculturalism as an answer to Europe’s social problems: renewal, demographic growth in an ageing society, fresh and necessary labor forces, perhaps even colored by a broader view of cosmopolitanism. Today, a growing number of nations of an expanding Europe—a Europe that however counts less and less on the world stage—consider it to be a cause of their social problems. That perception has led some mainstream politicians, including British Prime Minister David Cameron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, to publicly denounce multiculturalism and speak out against its dangers. It has moreover fueled the success of far-right parties and populist politicians across Europe, from the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands to the National Front of Marine Le Pen in France. And in the most extreme cases, it has inspired extreme acts of violence, such as Anders Behring Breivik’s homicidal rampage on the Norwegian island of Utoya in July 2011.

According to multiculturalism’s critics, Europe has allowed excessive immigration without demanding enough integration—a mismatch that has eroded social cohesion, undermined national identities, and degraded public trust. Multiculturalism’s proponents, on the other hand, counter that the problem is not too much diversity but too much racism.

But the truth about multiculturalism is far more complex than either side will allow, and the debate about it often devolves into all kinds of sophistry. Multiculturalism has become a mere proxy for other social and political issues: immigration policies, national identity, political disenchantment, working-class decline. Different countries, moreover, have followed distinct paths. The United Kingdom has sought to give various ethnic communities an equal stake in the political system. Germany has encouraged immigrants to pursue separate lives in lieu of granting them citizenship.

TERRORISM IN FRANCE CHANGES SOCIAL POLICIES

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he question of French social policy and of social divisions has come sharply into focus in the wake of the recent terrorist attacks in Paris. Assimilationists have long held multiculturalists policies responsible for nurturing ‘homegrown’ jihadists in Britain. Now, they are forced to answer why such terrorism has been nurtured in assimilationist France, too. In reality, all that those perplexed sociologists had to do was visit on foot the northern periphery of Paris as in St. Denis to find the answers: underdevelopment, neglect, absence of legality. France’s close historical relationship with the Maghreb determined its preference for assimilationsim policies. The Algerians were there, French citizens. Despite the ferocity of the separation of Mother France and Algeria, the relationship survived and influenced French relationship with others, from Morocco to Tunis. Go to the Chateau Rouge quarter adjacent to Montmartre in Paris and meet them, or listen to a new recording of modernized RAI folk music, with pianos and other Western instruments and songs sung in Arabic with a French accent and you will hear the results of failed assimilationism..

So you must distinguish between diversity or resemblances as lived experiences and multiculturalism as a political process: The experience of living in “a society that is less insular, more vibrant and more cosmopolitan” is of course something to welcome and cherish. It is a case for cultural diversity, mass immigration, open borders and open minds. As a political process, however, multiculturalism means something very different. On the one hand, it has allowed the political right–and not just the right– to blame mass immigration for the failures of social policy and to turn minorities into the problem. On the other hand, it has forced many traditional liberals and radicals to abandon classical notions of liberty, such as an attachment to free speech, in the name of defending diversity. That is why it has come to seem critical to separate these two notions of multiculturalism, to defend diversity as lived experience – and all that goes with it, such as mass immigration and cultural openness – but to oppose multiculturalism as a political process.

MULTICULTURALISM IN GREAT BRITAIN

In February 2011 David Cameron a speech arguing against state multiculturalism:

“Under the doctrine of state multiculturalism, we have encouraged different cultures to live separate lives, apart from each other and apart from the mainstream. We’ve failed to provide a vision of society to which they feel they want to belong. We’ve even tolerated these segregated communities behaving in ways that run completely counter to our values. So, when a white person holds objectionable views, racist views for instance, we rightly condemn them. But when equally unacceptable views or practices come from someone who isn’t white, we’ve been too cautious frankly– frankly, even fearful–to stand up to them. The failure, for instance, of some to confront the horrors of forced marriage, the practice where some young girls are bullied and sometimes taken abroad to marry someone when they don’t want to, is a case in point. This hands-off tolerance has only served to reinforce the sense that not enough is shared. And this all leaves some young Muslims feeling rootless. And the search for something to belong to and something to believe in can lead them to this extremist ideology. Now for sure, they don’t turn into terrorists overnight, but what we see–and what we see in so many European countries–is a process of radicalisation.

|

Cameron concluded that Britain “should encourage meaningful and active participation in society, by shifting the balance of power away from the state and towards the people [and] also help build stronger pride in local identity, so people feel free to say, ‘Yes, I am a Muslim. I am a Hindu. I am A Christian I am also a Londoner a Berliner too.'”

Johann Hari, a British journalist for The Independent, a social democrat and atheist, and harshly critical of multiculturalism, writes: “Sharia courts highlight in their purest form the problem with multiculturalism. It has become a feel-good doctrine mindlessly celebrating ‘difference,’ without looking at what that difference actually means. Yet many people feel instinctively uncomfortable when we talk about ditching multiculturalism—for a good reason. The only alternative they are aware of is the old whiter-than-white monoculturalism. This is the view that if people are going to live together, they need to look and feel similar, and have a tightly prescribed shared identity. (But) there is a better way for the state to understand and regulate human differences … It is called liberalism. Liberal society allows an individual to do whatever he or she wants, provided it doesn’t harm other people. You can choose to wear PVC hot pants or a veil. You can choose to spend all day praying, or all day mocking people who pray. Where a multiculturalist prizes the rights of religious groups, a liberal favours the rights of the individual.”

Today’s mass migrations of peoples—literally flights from war and oppression caused by new forms of neo-colonialism and hybrid wars conducted by the U.S.-led West has no relationship with classical immigration. Conservatives and right-wingers even reject the use of the word refugees to describe the man, wife and three children who risk death on the dangerous waters of the Mediterranean Sea to escape the bombs dropped by aircraft of the countries to which they are fleeing to. Multiculturalism or monoculture are not on refugee minds, although in the best of circumstances they hope for work, some form of assimilation, a decent social life, and a future for their children. I wager there is little awareness today of the old dream image of what was once called the melting pot of “America”, when every new immigrant tried to be more American than eight-generation Americans.

ITALY

Italy, where I have lived for several decades, was until recently an emigration country. Italians and people of recent Italian abstraction abroad outnumber Italians in the homeland. If in the 1970s under 200,000 non- European foreigners lived in Italy, today Italy hosts five million! Italy had little experience with real immigrants. Italians once thought of themselves as non-racists. However, since today’s massive migrations of refugees began (and even though Italy is chiefly a transit country), the irrepressible arrival of masses of refugees entailing the presence of different cultures and religions, Italians have faced the fact that racism exists also here. Italy has had specific difficulties in even acknowledging the new cultural pluralism brought by refugees. In the more recent context of social and cultural change in Europe, Italian society is also going through a phase characterized by reactive identities and cultural conflicts, coupled with a dramatically ageing population and low birth rate, (while its well-educated youth is moving elsewhere—Germany, UK, the USA—in search of employment commensurate with their capabilities). Italians too are producing a diffused anti-multiculturalist opinion, even though multiculturalist policies have not been openly implemented. Thus, on the one hand, the situation in Italy has so far prevented a radical perception of cultural and religious differences, particularly concerning Islam. But on the other hand, positive actions in favor of migrants can also be observed, especially at the local level, attributable to a great extent by the inherent hospitable nature of Latin peoples, while at the same time providing fertile terrain for brutal exploitation of cheap labor among illegals. Rome too has its China town and ghettos of African peoples. At the same time, there are also many longtime, well-integrated Somalis, Eritreans, Ethiopians and Egyptians and a major, beautiful mosque in a plush urban area of Rome. Legal immigrants of earlier periods, many of whom are today integrated, are an absolute necessity in north Italian industries where a labor shortage exists. However, even there the transfer of industrial concerns abroad because of cheaper labor and lower taxes, to Romania and elsewhere in East Europe, and the increasing use of robots and machines for the work of man on assembly lines have more or less stabilized industrial labor supply and demand. Yet Italy has still not passed laws based on ius soli granting citizenship to children of immigrants born in Italy; the principle of ius sanguinis (citizenship requires that one parent be Italian) still governs. The ius sanguinis requirement still prevails in most of Europe, except France.

GERMANY AND MULTICULTURALISM

In the late 1950s, Turkish workers arrived in West Germany to fill the demand for cheap unskilled labor in a booming post-war economy. That mass trans-migration was formalized in 1961 when an agreement was signed between Bonn and Ankara paving the way for the first wave of Turkish Gastarbeiter (guest workers) to come to Germany. Many of them never left, creating a minority community that changed the demographics of the country forever. They came to fill Germany’s need of healthy, unmarried workers. Turkey was more than willing to help meet that demand. In 1964, the recruitment treaty was changed to allow the Turkish workers to stay for longer than two years. It was too expensive and time consuming to constantly hire and train replacements. Later, the workers were even allowed to bring their families with them. Today, around 3 million people with a Turkish background live in Germany,

In a speech on Dec. 14, 2015 in Karlsruhe, a city dominated by the refugee crisis, German Chancellor Angela Merkel said that multiculturalism in Germany remains “a lie,” telling immigrants to “obey our laws, values and traditions.” Germany’s refugee policy had attracted praise from all over the world. Time magazine and the Financial Times newspaper recently named Chancellor Merkel Person of the Year, while one thousand Christian Democratic Party delegates applauded her for so long at her party’s convention that she had to stop them.

Richard Noack, writing from Europe, remarked that the speech that followed must have surprised supporters of her policies: “Multiculturalism leads to parallel societies and therefore remains a ‘life lie,’ ” or a sham, she said, before adding that Germany may be reaching its limits in terms of accepting more refugees. “The challenge is immense,” she said. “We will reduce the number of refugees noticeably.” Merkel was repeating a sentiment she first voiced several years ago when she said that multiculturalism in Germany had “utterly failed. The tendency had been to say, ‘Let’s adopt the multicultural concept and live happily side by side, and be happy to be living with each other.’ But this concept has failed, and failed utterly,” she said already in 2010.

The fact is, Germans have grown increasingly weary of the influx of refugees. Newcomers, Merkel stressed, should assimilate German values and culture, and respect the country’s laws. She emphasizes today that despite her commitment to limit the influx of refugees, she was standing by her decision to open the borders earlier this fall. “It is a historical test for Europe,” she said, adding that other countries in Europe should accept more refugees to take some of the burden off Germany. Refugees in need should be helped, she said, but she also suggested that not everyone who has come to Germany fulfilled “refugee” criteria. German authorities are expected to ramp up deportations in the coming months.

Although Merkel’s party, the Christian Democratic Union, overwhelmingly approved her refugee policy. her comments reflect a particular understanding of assimilation. Many Germans expect immigrants to quickly learn the German language and to contribute to their communities and work life.

Multiculturalism usually has a positive connotation in Germany, but to Merkel it has come to symbolize the emergence of isolated societies within Germany— and ultimately a failure of assimilating immigrants. Her policy toward the issue is supposed to avoid the creation of suburbs such as the areas around Paris where young immigrants are isolated from the rest of society. However, her Karlsruhe speech came at a sensitive time. Germany has opened its borders to approximately one million refugees this year, many of whom are still being accommodated in makeshift housing. Fights have broken out in multiple reception centers, raising fears about the country’s ability to deal with the influx. Local disputes have caused tensions in national politics as well. Last year, Germany’s influential Christian Social Union (the party of Bavaria in the South) made the ridiculous proposal that everyone in Germany should be required to speak German “in public and in private with their families.” The public backlash forced the party to retract the draft resolution.

Compared to 2010, when Merkel first voiced her criticism of multiculturalism, there was little reaction this time. The applause following her speech lasted nine minutes and again had to be interrupted by Merkel. The reality is that post-WW II Germany has never intended assimilation and eventual citizenship for immigrants. At war’s end, of Germany pre-war male population of 38 million, an estimated 5.3 million were dead and missing, plus a half million in Soviet prison camps and an incalculable number of disabled. A generation of working age males was lost. Germany needed manpower to re-open the factories and build public housing. The German term Gastarbeiter (Guest worker) became an all-European word, as besides Turks, Italians, Yugoslavs, Greeks et al arrived in waves. The many millions were never considered immigrants, nor did they consider themselves immigrants; they were Gastarbeiter. Germany was like one great cultural, demographic experiment. Special (slow) trains were organized to transport Gastarbeiter to Italy for holidays. However, some of the guest workers remained in Germany, opening the first ethnic restaurants, introducing food specialties from their native countries in a splurge of spontaneous multiculturalism. I personally remember the first French restaurant in Frankfurt and the first Turkish restaurant in Munich, while Germany like the USA was flooded with Italian restaurants and pizzerias.

It seems an irony that the birth of the European Union (EU), emerging from the Economic European Community (EEC) of 1951, a social union of peoples, has both supported a limited and different kind of multiculturalism and at the same time made the concept obsolete. The EU has deviated the multicultural idea into a loose union of ethnic member groups which enjoy free movement from one nation to another, peoples who often assimilate quite well into a foreign culture and language, but who continue to feel first Italian, then European; first French, then European. The idea of a single “European” culture into which Europeans and non- Europeans would integrate for better or worse in unrealistic. EU founders instead had hoped for a stronger union, a federation of states resembling the USA in its original form.

Falling prey to relativism

By Paul Cliteur

(I have abbreviated very slightly this article by the Dutch philosopher and professor of law. GS)

For many years, the official credo of the Dutch government regarding immigration was multiculturalism, an approach that fitted well with Dutch history and culture. Multiculturalism is affiliated with a postmodern outlook. The pivotal ideas of this vision of life are relativism (cultural relativism, in particular), a negative attitude toward Western political tradition, the cultivation of collective guilt for the transgressions of the colonial past, and other real or presumed black pages in Western history.

For multiculturalists, European civilization has been fundamentally on the wrong track since the Enlightenment. The Holocaust, Nazism, communism, slavery – these are seen not as deviations from the generally benign development of Western culture but as inevitable products of the European mind, which is inherently oppressive.

Multiculturalists also reject the universality of Enlightenment ideas of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, viewing them instead as isolated preoccupations of no universal appeal. It is preposterous and a manifestation of cultural arrogance, in this view, to invade foreign countries to export democracy and other Western ideals; it is likewise ridiculous to expect that religious and ethnic minorities in Western societies should be expected to adopt these ideas and integrate into liberal democracy. Minorities should live according to their own customs; and, insofar as national culture is at variance with non-Western ideas, the national culture should adapt itself to new conditions. This attitude has grave consequences for the way liberal society is organized. Think of the principle of free speech. The answer of postmodern cultural relativism is: refrain from criticism. Be reticent to comment on unfamiliar religions. Let reform come from within and avoid provocation and polarization.

The consequences of this approach are far-reaching. It would lead to a bowdlerising “purification” of the whole Western tradition of literature, art, cinematography, and even science. Postmodernism does not hold the Western tradition of rationality in high esteem, but would it also deny the right of the Western world to defend itself? The whole outlook that advocates the ideals of the Enlightenment, including democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, is to be replaced by the glorification of “otherness,” by non-Western cultures, and especially by the conviction that all cultures are equally valuable. Every predilection in favor of Western ideas has to be smashed to excoriate … the “West” in favor of the “Rest.”

(Such attitudes), it seems to me, would make Western societies very vulnerable to the ideological challenge that religious terrorism poses. Liberal democracy, with its institutions of free speech is, not necessarily better than alternatives. The only thing that the postmodernist wants to argue against is evangelical zeal.

What this attitude leads to can also be gauged in Murder in Amsterdam, a recent book on the Van Gogh killing written by the Dutch-American journalist and scholar Ian Buruma. Buruma holds a postmodern relativistic outlook. He tries … to apply postmodern relativism to the problem of religious terrorism. He also contends that an orientation toward the ideas and ideals of the Enlightenment is not significantly better or preferable to an orientation toward radical Islamic ideology. Radical Islam is a fundamentalist position, but the same could be said about “radical Enlightenment.”

…. Islamists are radical in the sense that they do not shy away from radical interpretations of their holy scripture. If scripture calls for the death of unbelievers and apostates, the true believer should not shy away from fulfilling the will of God and killing the unbelievers and apostates, in particular if they have committed the crime of blasphemy.… both radical parties believe in universal values. Both parties believe they are struggling for a righteous cause and for that very reason are not relativists. So both are fundamentalists.

… of course, every judicious writer would feel uncomfortable with this silly exercise in semantics. Are these two positions really “the same”? Is someone who is a warrior with the pen really the same as someone who conducts his war by killing people and decapitating them? Both Chamberlain and Hitler had moustaches, but it would be absurd to attribute any significance to this similarity. Of course, both radical Islam and radical Enlightenment are “radical,” but that does not make them anymore the same than a radical plan to alleviate hunger and suffering in the world is really the same as a radical plan to eradicate the Jews or any other ethnic or religious minority from this world.

Finally, it may be true that radical Islamists believe, as do adherents of the Enlightenment, in “universal values.” But so did Immanuel Kant … Most moral philosophers believe in universal values. That does not make Kant (a) “fundamentalist.” The Universal Declaration of Human Rights presented by the United Nations in 1948 is also a “universal creed.” The United Nations proclaims this list of human rights as a “common standard of achievement.” That does not make the United Nations an assembly of fundamentalists or dangerous terrorists. Or are they, in the eyes of postmodernist critics of modernity?

The reasonings of Buruma and other postmodern relativists have preposterous consequences, but these consequences logically flow from the postmodern outlook. Buruma also plays with the word purity. He writes that “the promised purity of Islamism” is not really different from “radical Enlightenment.” That would imply that Sayyid Qutb, the ideologue of radical Islam, would not be so different from the godfather of “radical Enlightenment,” Baruch de Spinoza.

…. this relativistic—or rather, nihilistic—position … makes Western societies easy prey for the ideology of radical Islamism. If Western societies think they have no core values important enough to fight for (by peaceful means), then there is no reason for immigrant minorities to accept them. If the dominant ideology in Western societies is that democracy, the rule of law, and human rights have no specific quality that makes them superior to theocracy, dictatorship, and authoritarianism, there is no need to oppose the radical assault directed at Western democracies by the teachers of hate. Postmodern-value relativists not only deny the superior quality of Western values but even contest that people may defend those values against the assault that is being made on them. Demonizing every criticism on religious mentalities as “polarizing” and “provocation” denies even the right to defend democratic institutions. That would be a suicidal position.

What remains a mystery is why many intelligent people stick to the postmodern frame of mind, even though so many intelligent writers—Terry Eagleton and John Searle, to name just two—have thoroughly deconstructed its tenets. I think this has to do with the postmodernist conviction that an attitude that they see as relativistic and pragmatic would help in the struggle against religious terrorism. They hope that, if we abstain from radical criticism of the terrorist mindset, we can pacify the most radical elements. This is a great delusion….

Paul Cliteur is a professor of jurisprudence at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

This article is a shortened version(and again cut by me) of the original which was published in the Free Inquiry. February/March 2006 edition and on the website of the Council for Secular Humanism.

The following short story, sketched out in a café in the Turkish district of Rotterdam in 1979 reveals some of the widely varying reactions of immigrant Turks themselves to acclimatization (or refusal to acclimatize) in Europe, i.e. the effect on the moral values on the private life of individuals transplanted in a radically foreign society.

TURKISH DELIGHTS

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]is dark face projected toward the rain-blurred windshield, Ibrahim’s body was unusually stiff and erect. The powerful windshield wipers slashed relentlessly but ineffectively at the unyielding rain while the constant splash from the intense traffic on the four-lane highway isolated the big car in a cloud of impenetrable muddy spray against the walls of which his headlights seemed to ricochet back into his eyes.

-Just what I needed—he thought—this blinding rain in this indecipherable land. It’s hard enough just finding my way into The Hague. But then, everything has gone wrong since they arrived, finally, for their first visit from the homeland.- The others had fallen silent, hypnotized by the night rain, the methodical slapping of the wipers, and now the regular flashing of the city lights in the distance.

“Sofia,” he asked, his voice louder than intended shattering the peculiar silence “do you remember where we have to turn right?” He recalled that the great Western hotel was someplace to their right, just after the Royal Palace which he hoped would be visible.

“You still don’t know, do you,” Sofia teased maliciously. “How many times have you been in The Hague anyway? What if it’s only twenty kilometers from home, you are lost once you leave the Schietbaanstraat”

In fact a big difference between Sofia and her husband was that he had never been aware of the wall around their life of home and their restaurant. Sofia, on the other hand, was stunned each time she emerged from the darkness of the caverns formed by the long narrow streets of Bajonetstraat and Adrianastraat into the lights and spaces of the Nieuwe Binnenweg. Even on stormy black days like today exit was like stepping across a forbidden threshold into a bright and magic world. Ibrahim usually responded to such frivolity: “Nieuwe Binnenweg might have more shops but it’s not so different even from home in Izmir.”

“Turn here, then to the left toward the hotel,” Sofia said and sighed purposefully loud so that Ibrahim’s parents registered her frustration.

“I know, I know, the French restaurant is in the street behind.” –What possessed me to want to bring them to this fancy restaurant anyway? Maybe it was more for Sofia than for them. Still, they can see that I was right to move to Europe. They can see that I am a respected man here. Our house in the city, a Mercedes, the children learning well in school.- But what seemed to really count for Ibrahim was his parents’ image of him as reflected through Sofia’s eyes.

Sofia was an exceptionally beautiful woman by any standards. And everyone knew that Turkish women are the most beautiful of all. She herself found that she had become more beautiful in the West, although she knew she was very attractive in both the East and the West. She recognized female beauty in all its forms. Dark and petite and sultry, she nonetheless admired without a trace of jealousy the tall blonde long-legged Nordic women. On the other hand, it had cost her no small quantity of self-recrimination and tears to realize that in the eyes of Ibrahim and some of his friends her flowering beauty was synonymous with the evils of westernization.

“You are only jealous,” she answered his frequent criticisms.

“I am not jealous in the Western sense. You are a Turkish woman. I am a Turkish man. We have our own traditions to follow,” Ibrahim preached to the unconvinced and partially emancipated Sofia. “And look at the children. They speak Turkish so poorly. You are ashamed of your own language. In my home, Turkish is the spoken language. Your language. My language and the language of my children. When we return home they will not be strangers!” Ibrahim had simply brought Turkey along with him on this extended stay in Rotterdam.

Sofia’s response to such talk had become unambiguous: “I have no intention of ever returning to live in Turkey, so why do I and the children need Turkish. We must learn English, like the Dutch people do, and also French.” In the mind of the disoriented Ibrahim such blasphemy stirred images of kidnappings and he didn’t know what other violence.

Their heads lowered, they leaned forward into the cutting icy rain and the hard wind blowing up the tunnel up Denneweg from the direction of the Mauritskade. Ibrahim held his father’s arm and stopped to peer into the window of the bodega-bar Sofia had once taken him to, just to get new ideas for their own bar, she had explained. Ibrahim shouted into the old man’s ear: “I wanted to show you a Dutch bar, with its candles and music, but the bad weather has chased everyone home. Anyway, our Turkish bar is much more interesting.”

“Hah!” exclaimed Sofia, she and Mother pressing against the men. “You just don’t understand such places, my husband.” She always saw sparkling white tablecloths and crystal chandeliers and silent black-suited waiters, and she danced to soft Western music. Ibrahim could never have understood that the Hotel des Indes would have pleased her more on this evening, although she had no concept that the very name of the famous hotel recalled the worst of Dutch colonialism in the East.

Ibrahim’s father turned and looked hard at his daughter-in-law. “Your wife has become very talkative,” the old man said, again embarrassing his son.

-But she is right in a way,- Ibrahim thought. -The ISTANBUL is like a home. Just being there at ease behind my desk facing the bar, the boys running things smoothly, the snack bar in the back, the tables in neat rows, even the pinball machines she hates. Then the real Turkish restaurant in the other room. The best in all of Rotterdam. Certainly the only one with Turkish brass tables and fur-covered puffs and couches and water-pipes. Didn’t they write about it in the newspapers, and now it’s full of foreigners every evening. And the guilders pour in! But still, the afternoons are the best time, when there are no foreigners, and we just talk. Almost like we weren’t even abroad. We can talk about our businesses and I settle my accounts, and … and if it just weren’t for that vulture Turan … Turan! Turan! Now they were gossiping about him and Sofia. Not to me, but I’ve heard the talk. Turan in your Italian clothes, and your big cars, and your grand manners, and that entourage following you all the time. Some night someone will meet you alone …. I know how you rob our own countrymen. I’ve heard the stories. And the money you lent me when I bought the ISTANBUL. I’m still paying you, and I’ll never finish paying. So now you want Sofia as part of the interest.-

The French restaurant was worse than Ibrahim could have even imagined, and more splendid than Sofia expected. Turan must have recommended it to her. She now entered like a queen and felt immediately at home. Ibrahim helped his nonplussed and unimpressed parents to the discreet table near the rear that Sofia had reserved, Ibrahim had agreed to come to The Hague and the French place in the hope of making a bella figura with his parents. Now he was instead chagrined that he couldn’t understand a word of the menu; and then, suddenly, in all the elegance, and bewildered by the waiter who began speaking to them in French, even his rudimentary Nederlands failed him.

“May we have a Dutch language menu?” Sofia said easily to the haughty waiter in her good Dutch.

“You just keep quiet,” Ibrahim reprimanded her. “I will do the ordering here.”

“Je suis vraiment desolé. Nous n’avons que le menu français,” the waiter said indignantly. “But, uh, may I advise you?” he added in Dutch.

“Well, yes …” Sofia started to say.

“Sofia is very talkative now,” Father said again, looking at Ibrahim who was still fumbling with the useless French menu.

His parents had never been more Turkish. Father’s slick head reflected the candlelight. His heavy eyes were impassive as he pulled and smoothed his long mustache. Mother, dressed elegantly in her eternal black, stared steadily into the flickering light.

Sofia was embarrassed as Ibrahim struggled through the ordeal of selecting a few quasi understandable dishes. The impatient waiter said then to Sofia in Dutch as if doubtful about the order: “Well, Madame, I hope the dinner will be satisfactory.” In her embarrassment unable to even look at Ibrahim and his parents, Sofia continued to stare toward the hors-d’oeuvres and sea food display table.

“You probably would have preferred to stay in the ISTANBUL tonight,” she finally spat out.

“You might have liked it better also,” Ibrahim couldn’t resist saying. “Some of your friends are surely there tonight.”

“I don’t have any real friends in the ISTANBUL,” she said coldly.

“That is not what I have been hearing,” Ibrahim,” said, committing himself for the first time. He knew he had gone too far. It was because of the rain, the highways, the snotty restaurant, the menu, and the unintelligible French waiter. And then his wife insulting him in front of his parents. One long insult. All day, only semi-consciously he had been recalling certain details and putting them together.

-Even my friends have to suppress their smiles. They all know about it. Laughing at me behind my back. And Turan sitting there so suavely on his bar stool, surrounded by his henchmen, taking that fat yellow envelope out of his breast pocket and receiving and paying out in 1000 guilder notes. Everybody laughing at his jokes, holding onto his every word. Sofia also! Turn the handsome, his long black hair and sweeping mustache. A North Caucasian he says. The son of a Prince! Those stupid faded pictures of him in the tribal costume, waving a kinzhal as he whirls and lifts high one leg. All those white teeth and the black mustache. Just Sofia’s type too-

He looked at himself in the mirror on the opposite wall: thin hair slicked down, tan skin, and the gaping white scar running like an accusation from behind his left ear down under his chin. –Why they were just kids, stupid kids, breaking in like that late in the night, and if … if that Turan and his men hadn’t arrived in that moment, they would have finished me off … all for the few guilders I had in the cash drawer in those days.-

Father was silent. Mother’s very posture was a criticism. Haughty Sofia launched dangerous glances around the dining room. “Easy, my son.” Father said gently. “Those words are unimportant. The Frenchman was upset because he couldn’t understand what food we wanted. After all, we’re his guests. Now it will be all right, now that the misunderstanding has been cleared up.”

-So that’s it. All of this is just a misunderstanding. A misunderstanding when she arrived from the airport with them in the back seat, blowing the horn so loud outside the ISTANBUL. Why didn’t she wait for me to get in with them instead of driving slowly and making me follow behind on foot, all the way to our house? What did Father think about my walking along behind like a donkey? Just a misunderstanding, eh?-

Ibrahim had been too agitated. Too confused about his own identity. Father was always calm; he had that quality, something from the earth he had always worked. He knew who he was. Mother was passive, like always … and tired. Neither parent showed any reaction to their duplex upper house so richly furnished but overdone with the bizarre mixture of their Turkish with the Dutch influences Sofia had added. Father had ignored the plants and flowers but examined with an expert eye the Turkish carpets, after which he stared unseeing and without comment through the huge and never covered front windows through which passing strangers on the street could see right into their house, as if there was never anything to hide in this house! Bewilderment then filled Father’s eyes when the children, straining to comprehend his speech, could find no Turkish words to answer their strange grandparents from the East. “They are of your blood, Father,” Ibrahim said. “Yes, my son, of my blood, but today blood counts for less, for much less in your world.”“What do you mean, in my world? My world is your world, and that of your father, and your father’s father. And there are tens of thousands of your sons right here in Rotterdam, Father … we are still your sons.” “I wonder about that,” Father had said.

When the waiter slammed down the desert plates, father and son birth frowned. “It’s because we are foreigners, Father. That’s the way things are here. This waiter has become more and more insolent. Better to stay with your own people than be subjected to such humiliation. Things are more genteel at the ISTANBUL. Our waiters don’t slam down plates under the noses of foreigners.”

“That is what I mean to say,” Father said, and languidly and with punctilious precision dipped his fingers into the glass of water and dried each one separately with the white linen napkin. Sofia watched the procedure and frowned. Wondering if he should do that she started to say something until she caught Ibrahim’s unspoken warning. Ibrahim caught the waiter’s ugly smile and wondered what it was all about. “Now he’s openly laughing at us!” he said anyway.

“Waiter, bring us the check,” he squeezed out in Dutch, while Father smiled warmly toward the tall, very thin waiter.

“The old gentleman is very charming, the waiter said in perfect Dutch when he presented the check.

Ibrahim didn’t deign him a glance. “He’s mocking us,” he repeated to no one in particular.

“Son, I think he is a nice man … now that he has served us and we have eaten. He was nervous at first. I think because he does not speak our language.”

-Now my own father is contradicting me, and in front of the women. It’s even obvious to that smirking waiter. My people do all their dirty work, and they laugh at us.-

His was an oriental rage, he felt, trembling just below the surface of skin and demeanor. He was gravely stiff, humiliated and furious as he helped Mother into her coat and then walked out the door without a glance at anyone. The rain had stopped, the wind had stopped, and the only thing Ibrahim felt, physical or emotional, was a great, thick expectancy in the air. Expectancy and incompleteness, after a day and a half of humiliations. There were few cars now on the autoroute back to Rotterdam. The lights of the night traffic were soft and matted. He was aware of the last slice of a declining moon and almost summer stars high over the flat fields. After the rugged Turkish coasts and the hill country of Anatolya, he had never appreciated these wide fields divided in such a regular way by the straight canals. The old man slumbered in the seat beside him, and he knew Mother was staring at the back of his head.

Sofia’s eyes followed dreamily the white wafts of clouds drifting close behind the spires of Delft’s New Church and then the Old Church. She imagined herself again at the sidewalk café on the Marktplein facing the Stadhuis, the gay and boisterous European tourists, the crowds of students, the Delft Blue shop on the corner where she had timidly bought four square tiles before he bought for her the elephant earrings, the handsome young American who spoke to her, and then her dark and dangerous companion lifting his eyes lazily from his beads and looking the youth so intently in the eyes that he just stammered something and walked away. She had blushed in embarrassment.

The knuckles of Ibrahim’s hands were white as he clenched and unclenched the wooden steering wheel, one of the things he most loved in his car. His lips worked and his Adam’s apple bobbed as he swallowed nervously. From time to time he exaled an audible sigh.

-I’ll take them upstairs. Father is tired, and Mother will follow him to bed. Sofia can … well, tonight, we’ll see. This can’t go on any longer. Turan is a big and powerful man, but he has gone too far this time. A man can’ live in fear all the time. A debt is a debt. But my wife, the stupid little whore she has become, he wants her too. He wants my hotel. He could never bear it that I have the only Turkish hotel in Rotterdam, the only restaurant. That’s why all his airs, sitting at the bar, taking in his money, pulling at his beads while dressed in those fancy Italian clothes, telling his stupid stories and all his debtors laughing. They have lost their dignity. He’s not even a good Turk anymore. He’s like a desert jackal waiting on a dune, a great hungry buzzard circling over us, waiting. Now he wants Sofia.-

Ibrahim sat quietly behind his desk, and waited. He checked the receipts for the evening, took the cash from the bar and from the waiters while the last customers left. He kept an eye on Turan holding court at his usual corner of the high bar, a strong young man on his right, a fat, bald-headed intellectual type on his left, and the two bodyguards standing just behind him. At a table in the back, a chubby, older man with rosy cheeks and wearing a dark, beaked Dutch cap was finishing a plate of beans and a glass of Pils, and reading a Turkish newspaper. The foreigners, first those who had come for good Turkish food, and then later, the slummers, had all deserted the Turkish room and the lights there were extinguished.

Ibrahim was like cold steel. The habitué’s looked at him strangely. He waited. Then he began to stare fixedly at Turan, whose eyes met his at regular intervals. Turan’s eyes said nothing but Ibrahim saw that his mouth was twisted and his smile sardonic and humiliating.

-He wants it all. He wants to take all this. What can Father think of my life? Of me? Of the way she talked to me tonight. I should have beaten her. That smirking waiter and all their fancy manners. Sofia and her Western ways, speaking Dutch to my children and never satisfied anymore.

Our family’s honor is at stake, I can’t even face my friends as long as that Turan is here. No, this can not go on any longer. Our village is better. Izmir is better. I’ll take the children, take Sofia too. But Turan … the blood-sucker Turan, the … seducer of married women, he must go. Turan must die.

The bright young bartender, five years in Holland and on his way up after two years in swank Swiss resorts, was the only person not surprised by Ibrahim’s attack. It was part of his job to watch people and anticipate them. Ibrahim was a taut wire.

When he suddenly ran toward the bar with his thin kinzhal pointed at waist level, Omar, without hesitation threw himself across the bar, yelling “No! No! No!” and partially blocking the maddened Ibrahim with his body. Turan’s bodyguards made short work of the mute assailant.

Turan recovered his sangfroid immediately and before sliding off the high stool, he pressed Omar’s hands in his.

“What about the guy at the table back there?” someone asked.

“Oh, I’m sure there’s no problem. He didn’t see anything,” Turan said, gazing at the man in the cap who didn’t even look up.

At the door, Turan stopped theatrically and said to Omar: “I’ll see you in a few days. I think you will be needing a better situation.”

Then he hesitated, frowned as he looked down at the pale blue beads wound around the fingers of both his hands and then at the small crumbled

figure lying at the foot of the bar, and said in a voice louder than usual: “Actually, he just made two mistakes. He married the wrong woman and he should have stayed at home. But … any of us can make the same mistakes.

The End

Rotterdam,

March, 1979

Gaither Stewart

Our Senior Editor

based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

=SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

free • safe • invaluable

If you appreciate our articles, do the right thing and let us know by subscribing. It’s free and it implies no obligation to you—ever. We just want to have a way to reach our most loyal readers on important occasions when their input is necessary. In return you get our email newsletter compiling the best of The Greanville Post several times a week.

[email-subscribers namefield=”YES” desc=”” group=”Public”]

Born and raised within the animal rights movement, Wolf Gordon Clifton, currently serving as Executive Director of Animal People Inc, publisher of the Animal People Forum (animalpeopleforum.org) has always felt strongly connected to other creatures and concerned for their well-being. Beginning in childhood he contributed drawings of animals for publication in Animal People News, and traveled with his parents to attend conferences and visit animal projects all over the world. During high school he began writing for the newspaper and contributing in various additional ways around the Animal People office. His first solo trip overseas, to film a promotional video for the Bali Street Dog Foundation in Indonesia, led him to create the animated film Yudisthira's Dog, retelling the story of an ancient Hindu king famed for his loyalty to a street dog. It also inspired lifelong interests in animation and world religion, which he went on to study for college at Vanderbilt University. Wolf graduated in 2013 with a Bachelor of Arts in Religious Studies and minors in Film Studies and Astronomy. In 2015, he received a Master of Arts in Museology and Graduate Certificate in Astrobiology from the University of Washington. His thesis project, the online exhibit Beyond Human: Animals, Aliens, and Artificial Intelligence, brings together animal rights, astrobiology, and AI research to explore the ethics of humans' relationships with other sentient beings, and can be viewed on the Animal People Forum. His diverse training and life experiences enable him to research and write about a wide variety of animal-related issues, in a global context and across the humanities, arts, and sciences. In his spare time, he does paleontological work for the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, and writes for the community blog Neon Observatory.

Born and raised within the animal rights movement, Wolf Gordon Clifton, currently serving as Executive Director of Animal People Inc, publisher of the Animal People Forum (animalpeopleforum.org) has always felt strongly connected to other creatures and concerned for their well-being. Beginning in childhood he contributed drawings of animals for publication in Animal People News, and traveled with his parents to attend conferences and visit animal projects all over the world. During high school he began writing for the newspaper and contributing in various additional ways around the Animal People office. His first solo trip overseas, to film a promotional video for the Bali Street Dog Foundation in Indonesia, led him to create the animated film Yudisthira's Dog, retelling the story of an ancient Hindu king famed for his loyalty to a street dog. It also inspired lifelong interests in animation and world religion, which he went on to study for college at Vanderbilt University. Wolf graduated in 2013 with a Bachelor of Arts in Religious Studies and minors in Film Studies and Astronomy. In 2015, he received a Master of Arts in Museology and Graduate Certificate in Astrobiology from the University of Washington. His thesis project, the online exhibit Beyond Human: Animals, Aliens, and Artificial Intelligence, brings together animal rights, astrobiology, and AI research to explore the ethics of humans' relationships with other sentient beings, and can be viewed on the Animal People Forum. His diverse training and life experiences enable him to research and write about a wide variety of animal-related issues, in a global context and across the humanities, arts, and sciences. In his spare time, he does paleontological work for the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, and writes for the community blog Neon Observatory.

an academic version of the Dr. Phil show where infantilized pedagogies prove to be as demeaning to students as they are to professors. Professors are now increasingly expected to take on the role of therapists speaking in terms of comfort zones but are rarely offered support for the purpose of empowering students to confront difficult problems, examine hard truths, or their own prejudices. This is not to suggest that students should feel lousy while learning or that educators shouldn’t care about their students. To the contrary, caring in the most productive sense means providing students with the knowledge, skills, and theoretical rigor that offers them the kinds of intellectual challenges to engage and take risks in order to make critical connections and develop a sense of agency where they learn to think for themselves and become critical and responsible citizens. Students should feel good through their capacity to grow intellectually, emotionally, and ethically with others rather than being encouraged to retreat from difficult educational engagements. Caring also means that faculty share an important responsibility to protect students from conditions that sanction hate speech, racism, humiliation, sexism, and an individual and institutional attack on their dignity.

an academic version of the Dr. Phil show where infantilized pedagogies prove to be as demeaning to students as they are to professors. Professors are now increasingly expected to take on the role of therapists speaking in terms of comfort zones but are rarely offered support for the purpose of empowering students to confront difficult problems, examine hard truths, or their own prejudices. This is not to suggest that students should feel lousy while learning or that educators shouldn’t care about their students. To the contrary, caring in the most productive sense means providing students with the knowledge, skills, and theoretical rigor that offers them the kinds of intellectual challenges to engage and take risks in order to make critical connections and develop a sense of agency where they learn to think for themselves and become critical and responsible citizens. Students should feel good through their capacity to grow intellectually, emotionally, and ethically with others rather than being encouraged to retreat from difficult educational engagements. Caring also means that faculty share an important responsibility to protect students from conditions that sanction hate speech, racism, humiliation, sexism, and an individual and institutional attack on their dignity.