For all their outwardly splendor, fox hunts are cold-blooded, highly choreographed acts of cowardice and distilled sadism against helpless animals. The moral imbeciles who ride to these hunts should be the hunted.

Prefatory note:

As some in our audience know, critics of fox hunts have been campaigning hard on British newspaper websites and various forums about bloodsports in England. Every Boxing Day the hunts ‘traditionally’ ride out to kill foxes. The Countryside Alliance (an association of “gentlemen devoted to the sport”—you know this type of rich, fatuous buffoon) is a very powerful body in England and Prime Minister David Cameron used to ride with three foxhunts in Oxfordshire. His government cabinet is mainly made up of CA people, hence the slaughter of Britain’s badgers to placate the farmers (who are really responsible for the cause of tb as they move their cattle around and change name tags on their animals).—Patrice Greanville

THE SORDID TRUTH ABOUT FOX HUNTING

By Andrew Tyler (Originally written in 1997, but currently being posted through thousands of doors before the next UK 2015 election.)

INTRODUCTION

For more than two decades, Clifford Pellow served as a professional Huntsman with several packs of fox hounds in England and Wales. The last eight years of his hunting career were spent with the Tredegar Farmers Fox Hounds in South Wales. Always a stickler for the rules, Mr Pellow became more and more outraged at the abuse of foxes ordered by his Hunt Master in breach of hunting codes of conduct, until, unable to stomach it any longer, he protested. As a result he lost his job.

He took his complaints to the Masters of Fox Hounds Association, which held a mockery of an ‘enquiry’, and finally ‘exonerated’ the Hunt Master, Mr Howard Jones.

In November 1991, Clifford Pellow, at the invitation of the League Against Cruel Sports, attended a Press Conference in the House of Commons, where he described to the media and several Members of Parliament, several incidents during which foxes were abused in contradiction of the rules of the Masters of Fox Hounds Association during his career as professional Huntsman for the Tredegar Farmers Fox Hounds.

Mr Howard Jones, Master of that Hunt, who was publicly accused by Mr Pellow of being responsible for these abuses, launched a libel action against Mr Pellow. The case came to court on 24th November 1994 in Cardiff Crown Court. In his defence Mr Pellow called hunt supporters as witnesses to verify his allegations.

On 1st December, after a six-day hearing, the jury cleared Mr Pellow of libel. The court ordered Hunt Master Mr Jones to pay all the costs of the case – estimated to be almost £100,000. Mr Jones, however, continues as Master of the Hunt with the blessing of the Masters of Fox Hounds Association.

Award winning journalist Andrew Tyler was commissioned by the League Against Cruel Sports to interview Mr Pellow and write the compelling story of a man whose burning conscience caused him to turn his back on a sport which had enthused him from childhood, and in which he had risen to the top, but whose governing body pathetically failed him when he complained of horrific cruelty in breach of their own much-vaunted codes of conduct.

Clifford Pellow has since carved out a new living unconnected with bloodsports and is a member of the League Against Cruel Sports. The League and its active members now benefit from his advice and unique knowledge and experience. He now looks back on his hunting days with new eyes and can no longer justify the continuing existence of the ‘sport’ he once loved – even if conducted in accordance with the rules. However, it is possible that he would still number amongst hunting’s leading professionals today, had his less conscientious superiors supported him in upholding the standards they publicly and piously proclaim in defence of fox hunting.

—————————————————————————

Disillusionment came in stages. The Ruritanian cap-doffing and knee-bending, once an integral part of the grand mystique, grew wearisome – especially after he came to see the calibre of man to whom he was expected to defer. When, in 1985, he took a job with a Welsh hunt – the Tredegar – that played slack with the rules, the remnants of his pride disintegrated.

‘I was getting very bitter, if you like, about the things that I saw. It wasn’t what I’d been brought up to. It wasn’t the hunting that I knew, the sport that I had enjoyed, once loved and defended.’ In advance of hunting days, he says, foxes were caught in traps, put into sacks and, after being dragged across a couple of fields to get up a good scent, released for the hounds to slaughter. Bad sport. In one incident, a milk churn rather than a sack was used. In another, the terrified fox bolted from the bag into a farm where he fell into a manure pit. The farmer’s son shot him.

What made matters worse for Pellow was that, from the start of his career, he’d always been a man of starchy correctness, a disciplinarian who’d once been fired for inflexibility. Now, here he was playing his own part in the travesties. “I was as guilty as everyone else. Sickened by it, but guilty”.

He remembers one fox, caught and handed over by a local farmer, who was kept for a week in a 40 gallon bone bin, where he was sustained on liver and water. “I remember looking in on him on the Friday, looking at this beautiful creature, which he was, and thinking: Tomorrow this time you’ll be a thing of the past, ripped to pieces. Seventeen-and-a- half couple of hounds will be biting at you, each hound with 32 teeth.”

‘And before that there’s the fear as you’re grabbed by the tongs and stuck in the sack.’

‘I’ve held a fox many times by the scruff and brush and felt how petrified they get; their hearts banging away like hell; farting and excreting and peeing every time the hounds speak. And I’m the person giving him three seconds to live. I am responsible for it. Absolutely ghastly..’.

In June 1990, oiled by a few whiskeys, Pellow spilt his complaint to the Tredegar’s joint master at a hound show in West Wales. Pellow had been talking to another practitioner when his master called over, condescendingly: “Have you finished with my kennel huntsman, because I am ready to go?”

“I am not your fucking kennel huntsman”, Pellow replied. “I am not your anything mister!”

Three months later, disgusted by the hunting establishment’s failure to respond properly to his complaints of malpractice, he took his case to the old enemy – the League Against Cruel Sports. Before the year’s end, he was travelling to London with his wife, Barbara, to address a House of Commons press conference, at which he would denounce not merely the rule-breakers but the whole ‘cruel and pointless’ hunting business. Death threats awaited him on his return to his Machen home. A potentially costly libel action would soon follow.

I told her I wasn’t sure and she said: “Urn, you’re not going to back out are you?” And I said, “Oh no, I won’t do that”. And she said, very staunch, like: “Good!” So I knew she was following what I was thinking and I knew she was with me.

A couple of days later when I had been accused of lying by someone when they were interviewed on our local television station, and I told them that nobody calls me a liar and gets away with it, Barbara looked at me and said: “Go on boy, you show the bastards what you mean!”.

Clifford Pellow is still trying to disentangle his feelings about a ‘sport’ to which he devoted much of his childhood and all of his working life up until June 1990. He talks with almost starry-eyed nostalgia of the old-time ‘greats’ who trained him in his various jobs around the country – ‘proper, professional hunt servants’ like Jack Champion of Sussex, Jack Dark of Somerset and Jim Chapman of Yorkshire.

‘They wouldn’t have put up with the kind of nonsense I’ve seen in my time – like bagging, or tying a fox’s leg over its shoulder to slow it down for the hounds to catch. If you did that in their country, they’d put a whip around you, without a doubt.’

But, on reflection, he recognises that, even in his 1960s Golden Age, things weren’t quite so perfect. The rule book allowed, in those days, a fox to be dug up and thrown alive to the hounds. And it was also acceptable to cut the footpads of captured foxes, or dowse them in their own urine, before turning them loose, so giving the dogs a stronger scent to follow. While such trickery persists, it is, at least, formally proscribed.

‘The rule changes of the early 1960s were forced by public opinion,’ says Pellow. ‘For there was that same opposition as is happening today. Now, though, it’s probably even stronger’.

‘I remember you would be going through a village at night after a day’s hunting, and the children would run out and shout things at you like, “How many have you killed today, mister?” Today they run out and throw bricks and call you all sorts of rotten so and sos.’

Pellow was himself cast from such a mould. He dresses in the tweedy, striped shirt style of gentleman’s apparel from the early ’60s. His bearing is somewhat regimental, although gives way to quieter, melancholic interludes. His physique is compact and his stride brisk. He still has a crop of healthy black hair which brushes back ruthlessly, away from crisp, clean features. The dialect points to a life on the move, being a mixture of Welsh and Devonian. And there is the habit of laying sudden and startling emphasis on a word or phrase that, for the moment, means everything to him.

What he has always wanted, you suspect, and what he turned to hunting for, was a safe niche within a clearly codified and stratified world; a world of orderly dramas in which the role of honoured professional – the potent leading man with the licence to kill – would be his. Over the years, the thing unravelled. The game wasn’t played straight, he found out. And it wasn’t worth playing, anyway. It was an awful realisation for a man like Pellow, but he has had the courage not only to recognise it for his own sake but to make the discovery public.

He was born March 1943 in the mid-Devonshire village of Sticklepath and raised by his mother and grandparents after his father vanished when Pellow junior was just three years old. His quarryman grandfather was the quintessential working class hunt adept, whose Saturday ‘sport’ gave focus to a life of frugality and hard labour. With his bed-time stories, grandpa was the tireless mythologiser for the cause – the huntsman as stoic hero; the fox as bloodthirsty killer of chickens and lambs.

Clifford’s first memories of a hunt go back to when he was four. He was on his way to Sunday school in his best blue suit when a car backed into his drive and ran him over, breaking his leg.

After treatment, he remembers being pushed in a pram to where the hunt met at Sticklepath’s Taw River Inn. “A hound jumped up onto the pram and I still remember his name after all these years: Wallflower. That was the name the huntsman snapped when he put the whip around him”.

1 didn’t go on the hunt itself but I did see them take off from the back of the village. The hounds were barking – or speaking, as I learnt to call it – and, being a bit afraid, I hid under the table. Our house was quite close to the covert where they were and I thought for some reason they were going to get into the house and get me. My mum came in and said, “Don’t be so daft. It’s only foxes they chase.” A year later, nerves settled, he attended his first chase where he was ritually ‘blooded’. It was a pre-season event at which ‘un-entered’ puppy hounds were being taught, by the example of the older dogs, how to kill, and at which the main quarry were fox cubs aged 20 to 28 weeks.

We were outside the village of South Tawton. A cub had gone to ground under a bank. I saw him dug out. I was standing quite close, about 10 feet away. And I saw him carried alive from the earth into a nearby field where he was chucked 15 or 20 feet up into the air. When he landed, the hounds grabbed and tore him apart. Then the huntsman went forth and did the thing they still do today: cut off the brush (tail) and the pads and distributed them among different people. Then the mask (head) was removed and given away as a trophy for mounting.

Before the carcase was thrown to the hounds, the huntsman – Bill Tozer was his name; a big gruff man, who, to me was like royalty (I remember pacing up and down outside his house for half an hour just to get a glimpse of him) – he said to me, “Come here boy”. Then he stuck his finger into the carcase and placed two dabs of blood on my forehead and two on the cheek. I was bloodied. Years later, I myself used to blood the youngest member of the field.

But I remember being absolutely over the moon, that this man had caught hold of me and touched me. And, of course, you don’t wash it off. You let it wear off.

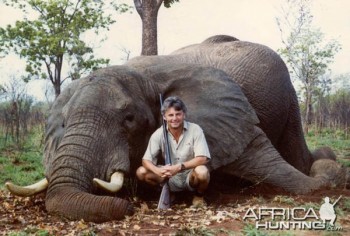

Hounds ganging up on their badly outnumbered victim. Trained to do so by abject human scum. They usually tear the poor fox to pieces. All so that some wealthy snobbish jerks should get their kicks. How could such people for countless generations claim moral superiority to rule a nation? Can anything of this nature be more eloquent about its sheer depravity?

From then on I went hunting as often as I could – always on foot, keeping up somehow by taking short cuts, like across rivers that the horses had to go around. Even though it was a minority of kids who went hunting. I’d always go with friends. Often their parents would come. But never my mum. Like my sister, she’s always thought it was cruel and used to grumble like heck at gramps when he was chatting about it.

By now, I was bunking off school to go hunting. I’d deliberately miss the free school bus so that I could go home and get sixpence from my mum for the omnibus. I’d use the sixpence to go to Tongue End and walk from there to wherever it was. One day, I was caught by my form mistress, Miss Harvey; she was at the hunt herself. All she did was smack me round the ear and say: “Enjoy your day boy!”.

He left school in 1958, aged 15, but was sacked from his first job, cutting kale, when he gave chase to a pack of hounds after they’d crossed the field in which he was working. His life’s ambition at the time was to be a policeman, rather than a hunt servant. “In those days” he says, “the police were respected. They had a certain power and trust. You had to be very, very careful and polite with them. They were something special.”.

Twice he failed the police entrance exam; poor maths letting him down. A succession of labouring jobs, mostly on farms, followed before he walked into his first hunt post in 1967 at the age of 24. It came after a chance meeting in a local pub with the top paid servant for the Tetcott Hunt. His name was Jim Deakin and he invited Pellow to a Saturday chase, then back to the kennels – ‘a great honour’ – where he watched the hounds being fed and their field wounds attended to. They went for a drink in the village inn where Pellow recognised, in the way the regulars deferred to his older companion; buying him drinks and manoeuvring to gain his ear; that to be a huntsman was to possess what he’d hoped to get from the police force: respect and honour.

On Deakin’s advice, Pellow wrote to the Masters of Fox Hounds Association (MFHA), hunting’s governing body, and asked to be put on their jobs-wanted list. Some months later came an offer from the Sussex-based Old Surrey and Burstow Hunt. Pay, for a seven day week, was £13 10 shillings, plus use of a tithed house and three tons of coal a year. As kennelman, his task was to look after the hounds and their quarters. Also, to prepare their food – skinning and carving locally-collected cattle and sheep who had perished, from injury or disease, before they could be taken to slaughter.

Ahead of him on the rungs to the top were the whipper-in (the huntsman’s ears and eyes on the hunting field) and the huntsman himself. While the master was the huntsman’s social superior, the man – guided by a committee – who hired and fired, it was the huntsman who was supreme when the chase was on. ‘The master is strictly the amateur’, says Pellow. ‘He might tell him where to go and what coverts to draw but it is entirely up to the huntsman where and when he does it’.

Downstairs as much as upstairs the lines of demarcation were fastidiously observed. To the kennelman, the huntsman was always Mr or Sir and his orders were not to be questioned. The hounds also had their clearly defined functions and, as soon as they failed to meet the terms, were ruthlessly expunged.

‘Until that time, they were kept in warm, clean kennels – bitches and dogs apart – where they slept together on bench beds in a huge pile. In the morning they were turned out into the grass yard for exercise’.

More stringent conditioning, known as walking out, began during the spring and became progressively more taxing as the November start to the season approached. At first, they are led on foot. Later, it would be by bicycle and, ultimately, by horseback for 15 mile cross-country trots.

Controlled breeding was by the ‘best’ male and female specimens, with the new-born in the charge of the kennelman for the first seven or eight weeks. Then they were turned over to a friendly local farmer or some other hunt supporter so that they could get used to a world of chickens, geese and tractors.

‘By the time they come back, it will, hopefully, be with some knowledge of the outside world. As summer wears on, they are introduced to the kennel activity proper and trained to obey the various commands. At this stage, they are still “un-entered”, which means they have no hunting experience. This comes during the cubbing season – starting in August – when they will be 12 to 18 months old. Those that fail to make the grade get the bullet; they are taken round the back and shot’.

Dogs past their prime (generally, older than five or six years) are also killed. Altogether, says Pellow, out of a pack of 60 animals, eight to ten are disposed of every season.

Old Surrey and Burstow was good hunting country, clean with plenty of open fields between coverts, hedges and ditches. The kill rate averaged about one a day. Most followers, of course, wouldn’t have a clue whether you’ve killed or not. But, for hunt servants, the kill is essential. It’s good reward for the hounds, sharpens them up, does them the world of good to have a bit of blood, as they call it.

The game, for the two seasons he was at the Old Surrey was, he says, played straight. The Master, local squire Sir Ralph (pronounced Raif) Clarke, was a ‘splendid fellow, a first class chap’. And, with his fellow servants, Pellow developed genuine friendships. He also received the respect he craved. ‘In the village you were the hunt. You were accepted by the local people as being something a little bit special.’.

The chance of more variety took him to the Seavington Hunt in Somerset. Here, he was allowed to ride the huntsman’s horse, drive a Land Rover and build or mend the odd fence… but never on hunting days. You weren’t actually allowed out of the kennels on hunting days. No, no! Good gracious me! A kennelman’s place, as the name suggests, is in the kennels.

His huntsman tutor at the Seavington was ‘the great’ Jack Dark, whom he remembers being as straight as squire Clarke from the Old Surrey. And yet, while the rules were observed, it was still a wounding business, and not only for the foxes. The field injuries incurred by the hounds came regularly and were often severe. But, like soldiers in battle, pain and infirmity were invariably deferred.

‘Every-day injuries were thorns in feet and minor and major rips from barbed wire. But I’ve seen hounds with their intestines hanging out, their eyes hanging down, and hounds with broken toes, broken legs, exposed testicles, and with ribs that have stuck through their flesh; a collision with a vehicle or with a horse would be the likely cause. I’ve never had a hound die in the field, though. One had a heart attack back in the kennels but she didn’t die until the Sunday morning’.

The horses also suffer. He has, personally, shot two in the field after they’d broken their legs. And he remembers another being so badly ripped across her chest and legs by newly-erected barbed wire, she was incapacitated for three months.

Many of the injuries to the dogs are dealt with by the hunt servants. ‘We consider ourselves, somewhat, as veterinary surgeons, which of course we aren’t. We don’t have the competence or the equipment, such as local anaesthetic. Yet, I myself have stitched a hound with ordinary needle and cotton. She was called Tablet and you could see the fleshy part of her ribs underneath a barbed wire tear. Happily, she made a good recovery and the vet congratulated me on a good job’.

On another occasion, he used a razor blade to sever a toe that had been dangling by the cord through much of an active day’s hunting. ‘I think it was then she felt it, for she gave out with a yelp. I washed, bandaged and put some cream on it and she was out again in a fortnight.’

Training the younger hounds and rebuking older ones for loss of concentration is also a bruising business. To scold a pup, the servant seizes the culprit and strikes him with the handle of the whip across the ribs – firmly enough, says Pellow, to raise a row of bumps. At the same time, the youngster is verbally reprimanded. An older dog who, say, shows interest in a sheep, will feel the whip’s leash. ‘And I can tell you, I’ve had a whip around me a couple of times, that it does smart a bit.’

The aspect of his hunting career that, today, causes him most remorse is his participation in ‘cubbing’ – the annual hunting and destruction of foxes aged no more than five to seven months, with the aim of teaching their family group as well as the new entry of hounds a suitable lesson.

‘It is a barbaric, hideous business in which the victims are still completely and utterly inexperienced and still dependent on their mothers.

‘It works like this: a huntsman, who knows his salt, knows there is a vixen in a particular covert and that there are five cubs with her. He goes into the covert and soon the hounds pick up the vixen’s scent and speak to her. They rattle around a bit. She’ll try to warn them off and, when the going gets tough, put her cubs to what she considers safety underground, in the earth.

‘She will then break covert to take the hounds – she knows, she’s experienced – away from the cubs. She’ll run across the fields and when she decides to go, she’ll go, never mind that there are 50 frightful people out there making noises and shouting. The hounds will come out and chase her a bit. This is a good thing. It enables your young hounds to know what happens when you’re hunting across a field.

‘After a field or field-and-a-half the huntsman will call them back. Now they go to the earth where the cubs are and they dig them out. And they don’t kill one or two or three but every one of them – after which they congratulate themselves on a beautiful morning’s cubbing.

‘Sometimes the cubs themselves break covert. I remember seeing one – no bigger than a ten-inch ball of fluff – up at the Lamerton (in Devon). When he saw all these people shouting at him he stopped, looked at the hounds in a clump of brambles a distance away and thought, “Oh well, I’m safe here”, and sat down. He was no more than ten feet away. And of course, the hounds came and he never moved. The master, a chap called Robbins, said to me: “Committed suicide that one.” When a second cub came out, the same happened to her’.

At the other end of the hunting season in March, many vixens are either already nursing their new-born cubs or at least heavily pregnant.

‘At the Tredegar, my last hunt, we had a vixen to ground. We just happened to come across her hiding, if you like. One of the bitches slipped away and started to mark the ground. The master said, “We haven’t had a kill so we’ll have this one.” When we got to it, I said to the master ‘Whoops vixen in cub sir!” And he said, “That don’t matter, we’ll still have her.” ‘We carried on digging but by now my blood is boiling, for this is against all etiquette. And, now, he said, “Don’t bother to shoot it, just fire into the ground and we’ll leave her to the hounds.” But I couldn’t.

‘I did shoot her. I couldn’t be bothered to go through the ritual, either, of holding her up. I just threw her and the hounds ripped her to pieces, and as they ripped her, there were four little baby foxes, not yet with hair. They were naked, or bald, or call it what you like. And the master went along and just screwed them into the ground with his feet’.

If cubbing is the practice that, when looking back, most ‘revolts and sickens’ him, the element within the hunt for which he reserves his greatest contempt are the terriermen. These are the hunt addicts who, aided by their fearless terrier dogs, block potential fox escape routes prior to the hunt and, on the day itself, dig out and either bolt or shoot animals who still manage to go to ground.

As well as ‘official’ terriermen – those attached formally to hunts – there are the ‘unofficials’, who freely assist the officials on hunt days for the pleasure of ‘working’ their dogs.

Often, this second category will race to be first to get their dogs down earths so that they can test them in underground battles with the cornered fox. They enjoy vying with each other to see who has the toughest, most aggressive terrier and will proudly display their animal’s, sometimes appalling, wounds.

Whenever a dog-fighting or badger-digging case comes to court, a terrierman will more often than not be at the centre of it.

‘Terriermen’ says Pellow, ‘are the thugs of the hunt. They are, quite frankly, a law unto themselves. They consider themselves in charge of things and completely indispensable. If you get too close when they are digging out and producing a fox – 90 per cent of the time by foul means – they become aggressive. I’ve heard them even tell a hunt master to bugger off and come back when they’ve finished.

‘They are aggressive because, deep down, they know what they are doing is wrong and they believe you will see something and report them. What’s in it for them is that they get the fox in the end. It doesn’t matter whether they throw it to the hounds, bash it on the head with a spade or stick an iron bar through its guts. And I’ve seen it all.

‘I’ve seen an iron bar stuck right through the lower jaw of a fox. “Whheeerrr, you bastard,” this one said to me “The fucker won’t get away now.” And he, literally, had him pinned with an iron bar through his nose and jaw.’

The activities of terriermen, says Pellow, are tolerated because the spectacle of such men at work is enjoyed by a large number of hunting’s foot followers. And it is these people who provide valuable revenue through their membership of supporters’ clubs.

After Jack Dark and the Seavington came The Holdemess Hunt in Yorkshire. Pellow was there, as kennelman, for one season, resigning over what he regarded was the shoddy treatment of his immediate superior and friend, Huntsman Patrick Read.

Read was put down a peg when the master – an amateur – decided to take charge of the field. Then came Read’s dismissal, by means of a letter and without compensation.

‘They didn’t even have the guts or the decency to tell him to his face.’

The next day I handed in my own notice and although they tried to get me to change my mind, with an offer of a better job, I wanted no more part of it. They had been, personally, very good to me, providing me with a couple of convector heaters when my son was born and, every week, filling my car with petrol. But the principal of the fact remained. And I am a stickler for principal. I won’t budge from it.’

Next, came a Hunt in North Yorkshire, where he was to witness a sadistic piece of trickery.

Riding ahead of his huntsman, he saw what he thought was a three-legged fox. He reported what he’d seen, they gave chase and eventually found the animal hobbling in a hedgerow. The dogs killed him. Pellow’s huntsman – ‘a first class professional and first class man’ – jumped off his horse to take a closer look and discovered that one of the fox’s legs had been tied up behind his shoulder. Someone had hobbled him to ensure a straightforward kill.

‘Jim Chapman called it a day there and then. On the way home he said something that has always stuck with me. He said, fox hunting is the best sport this country has ever produced. Therefore we must always play by the rules. He was brought up with that belief and because he saw the rules had been broken he stopped and went home.’

The Hursley Hunt in Hampshire was his next posting and, here, he finally reached the pinnacle position of huntsman. He joined as something less – as kennel huntsman, which placed him in charge of the kennels but not of the hunting field. This was under the command of one of the joint masters – a Colonel Douglas Drysdale. The Colonel had followed in the previous huntsman’s tail-wind for years. Now he, the amateur, wanted to do the professional’s job.

‘From the reports I’ve had, you’re a good chap,’ he told Pellow at the interview. He was doubly convinced after seeing Pellow in action. From May I, when Pellow was engaged, until the Thursday in November prior to the Saturday start of the season, the Colonel persisted with his ambition to take charge of the action.

Then, returning to the kennels after exercise, he confessed: ‘I must have been a complete and utter idiot if I think I can hunt hounds. As from now, you are promoted to huntsman.’ At this moment of opportunity, Pellow panicked: ‘I said “I’m not ready for the huntsman’s job sir”. And he said, “Well, see how it goes”’

They were due to start cubbing at 6.30 a.m. The Colonel called his new huntsman out 45 minutes early so that Pellow’s first moments in charge would be without the scrutiny of a critical audience. Drysdale was not only pleased with that first performance, he went on to describe Pellow to the Duke of Beaufort – hunting’s premier figure of the day – in superlative terms “Give this lad a couple more years experience and he’ll become one of the top six huntsmen in the country.”

‘If my grandfather could have looked down through the clouds he would have said, “Well done boy!”, because I had done it. I had got there. Walking out into the kennels in the morning half an hour after everyone else, it was ready for you. The yards were clean, the hounds were ready for you to exercise. And it’s “good morning sir”, with a little twiggle of the cap.’

Trouble at the Hursley started after two seasons following the Colonel’s departure; there had been a financial dispute with his committee members. A banker, Hugh Dalgetty, came in as master and now he wanted what the Colonel had originally sought but relinquished: command of the hounds.

The critical point of tension, however, related to Pellow’s marriage breakdown. He had met and wed his first wife, Anne, seven years earlier in 1968 while at the Old Surrey and Burstow. She was gentry; an uncle owned a vast estate in North Wales. She rode expensive horses, shot and hunted and did nothing much else in those days (though Pellow says she’s now a reformed character, living a practical life in the Orkneys. They remain friends.)

In 1975, news of their discord alarmed Pellow’s new master. He was worried the ‘antis’ would make great play of it and that the whole matter would be detrimental to hunting’s reputation.

‘I went down to his house, Lockerby Hall, which was quite a big house; he was local landed gentry. And I said, “I can’t be bothered with people like you”. His mum came in and they all stood up, and they’re not dukes or earls or lords. They’re just Mr and Mrs who happen to own 16000 acres.

‘And there was all this bobbing up and down like mushrooms in a frying pan and he was rattling on. He wanted me to resign at the end of the season because he was worried for the hunt’s reputation, but I said, “Oh, stuff it!” I chucked it in, I resigned – there and then.’

In his early days, the arcane nature of the hunt – the social stratification, the baronial etiquette – were a prime attraction for Pellow. But, at the Hursley, he came to see that his cherished world was unjust as well as risible. It was probably here that the seeds for that rich crop of discontent were sown.

A matter of personal pride, fiercely defended, led to the break, after five years service, with Pellow’s next hunt: the Tivyside in Cardigan.

He was out in the field one day chasing a fox when he came across a rider who, he said, caused him to send the hounds in the wrong direction, yet shifted the blame onto Pellow.

‘If a fox breaks covert and goes East, you turn your horse, take your cap off and point the way he’s going. But he didn’t, he holloaed and carried on looking into the covert. I put the hounds on the way he was looking, to which he said, “You’re hunting heel line (in other words, the opposite direction that the fox took) you daft bastard”.

‘I told him if he knew what he was doing he wouldn’t be looking in the wrong direction anyway. And he replied, “Don’t you dare speak to me that way, I happen to be this, that, and t’other.” And I said, “You also happen to be a bloody idiot”, and carried on.

A reprimand from his master followed, with an order to apologise; the offended party was an important hunt official. Pellow refused, insisting he had been in the right. His master insisted on obedience. The following day, Pellow formally resigned. For some weeks, the master stalled about accepting it. Pellow was asked to reconsider but he wouldn’t budge.

‘This chap accused me of doing something that wasn’t my fault and it wasn’t retracted. As anyone who knows me will tell you, I am a stickler for principle. I would not be moved.’

It was 1980. For one season he worked as huntsman with the Lamerton, his ‘home’ pack in Devon. He was fired from here for excessive strictness – a failing he concedes. ‘I wouldn’t have people riding in front of me, in front of hounds. Wouldn’t have people calling me Clifford. If they couldn’t say “Good morning sir”, don’t bother to speak at all was my attitude.’

With no job and no house, he, his two children and first wife (from whom he had still not parted) sheltered for several months in a caravan belonging to a local farmer. Their furniture was kept under tarpaulin for eight weeks on the lawn of the tithed cottage he had been forced to vacate.

His final hunt job was with the Tredegar Farmers in Gwent and it was here that he met his ‘adored’ second wife, Barbara.

He was to stay with the Tredegar for eight years, the longest any servant had remained. This was despite the fact he regarded the area as poor hunting country, with little opportunity to gallop through its small fields which were spiked with barbed wire and had lots of woodland and other cover. At the Tredegar a familiar theme re-surfaced: the master who wanted charge of the field rather than leaving it to his professional servant.

He considered resigning in 1985 but persisted. Jobs were no longer easy to find. ‘I stayed and gave the master all the support I could but then I noticed things were going wrong.’ Trapped foxes held captive in milk churns and in bone bins, then, on hunting day, put into bags and dragged across fields – all so as to impress the followers whose donations keep the enterprise afloat…this was not the ‘sport’ of his grandfather’s night-time stories.

‘It was “only a fox” at the end of the day, not a creature who could feel the same as you or I. The excuse given in arguments with the antis is that the fox is a killer, a pest. But when you’re at your hunt function, such as your hunt dance, you never hear the hunting fraternity say, “Oh, we’ll have to kill a fox tomorrow because it killed a chicken or a sheep.” That’s just an excuse. The hunting fraternity have hundreds of excuses for hunting but not one justification.

Following the bust-up with his master at the June 1990 Builth Wells hound show, Pellow lodged a formal complaint about the rule breaking with the Masters of Foxhounds Association. Several letters passed between the two parties. An inquiry time was set but, when Pellow asked for it to be re-arranged because one of his witnesses couldn’t attend on the given day, the MFHA refused.

“Their handling of it,’ he says, ‘was absolutely filthy. They had been given dates, places, what was done by whom and three signed statements – and still they allowed the guilty party to carry on. But then they were not going to be told what to do by a mere servant and, at the end of the day, that’s what we are. When I had asked for another date for the inquiry, I was told, “That’s it boy, you’ve had your chance.” I might at least have been called Mr Pellow. I was not a boy. I was 47 years old.’

The MFHA rejection drove Pellow into the arms of the League Against Cruel Sports and, before the year’s end, into a public denunciation of the ‘craft’ to which he’d devoted his life.

He briefly took a job as a senior security man for government offices in Gwent, heading a team of eight other men. At the back of the offices was a fox earth, occupied by a vixen and her young. Pellow regularly threw out food for them, brown bread and other scraps. Now he is running his own business delivering animal feed to farms in South Wales.

But there is still one ghoulish reminder of the bad old days: the head, or mask, of the fox from Tredegar whom he kept alive for a week in the 40 gallon bone bin. Though Pellow was not in at the kill, he arrived soon after and, personally, decapitated the slain animal. Until he abandoned hunting, the mounted trophy was displayed at his home. It now sits in a cupboard. One day, he says, he’ll sell it, and give the £60 or so it should raise to charity.

‘If you were to put two petitions in front of me – one for the continuation of hunting and one for the abolition, I would, without hesitation, sign for abolition. All the hunting fraternity think I’ve been got at. After all, I’ve had my encounters with the antis. I’ve galloped over them and put the whip around them. Caught one chap by the hair and galloped up the road and bounced him a little bit.

‘My opinion of the antis was that they were scum, scruffy, glorified hippies, and that they only did it for a free lunch, or £20, or whatever it was. Now, looking at it from today, the antis I’ve met – the active saboteurs – OK, they dress odd to say the least. They have long hair and have earrings stuck where they shouldn’t have earrings. But they are, when you think about them, genuine people who genuinely feel for the quarry. And, as such, I don’t think they would do damage to hounds or horses. It does happen but it is not their intention to do it.

‘When it comes to the fighting in the hunting field, I can only speak from the video evidence that I’ve seen, and 9 times out of 10, it is the hunting fraternity who start it.’

‘Yes, they think I’ve been got at. But nobody approached me. I made the approaches – both to the MFHA and, when that failed, to the League Against Cruel Sports.

‘Or they might say that I was not up to my job. Yet, the afternoon of my argument at the Builth hound show, I had been speaking to a regional secretary of the British Field Sports Society who wanted me to do a public relations stand for them at a major event in Swansea.

‘I believe that speaks for itself – that I must be regarded by those in the know as some sort of authority on hunting.’

By Timothy Bancroft-Hinchey, Pravda.ru

By Timothy Bancroft-Hinchey, Pravda.ru