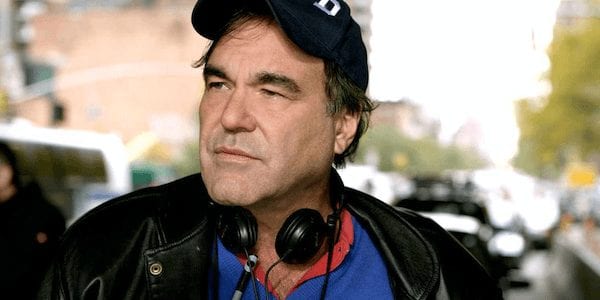

Film Historiography: Living El – The Making of Salvador

When Oliver Stone said he wanted to take James Woods, Jim Belushi and acid-fried journalist Richard Boyle to El Salvador to make a film about [a US-suported army and death squads ] fighting a leftist insurgency, few gave him a chance of succeeding. Even fewer gave him a chance of coming back alive.

Who went south of the border to bring you Salvador?

Vietnam vet-turned-maverick filmmaker. Followed screenplay Oscar for Midnight Express with Best Director gongs for semi-autobiographical ‘Nam films Platoon and Born On The Fourth Of July. Likes Indians and conspiracy theories. Dislikes the American government and women.

James Woods (Richard Boyle) – Lean American actor famed for his intensity, massive IQ and infamous affair with Sean Young. Oscar nominated for his remarkable turn as journalist Richard Boyle.

James Belushi (Dr Rock) – Thinner, less funny brother of John Belushi. A Saturday Night Live regular in the early 80s, Belushi blew his considerable Salvador cache on a succession of sickly family movies.

John Savage (John Cassady) – American leading man with an eclectic, eccentric CV (Do The Right Thing, The Deer Hunter, The Godfather Part III). Role in Salvador loosely based on real-life photo-journalist John Hoagland.

Richard Boyle (co-writer) – Respected investigative journalist and Olympic-level loon. Went to El Salvador in 1980 to cover the civil war for CNN. Accused Stone of failing to pay him his Salvador writer’s fee in full. Likes a drink.

Robert Richardson (director of photography) – A regular Stone collaborator, Richardson received Oscar nominations for his work on Platoon and Born On The Fourth Of July.

Gerald Green (producer) – American producer and head of Pasta Productions.

John Daly (producer) – British independent producer and David Hemmings’ partner in Hemdale Films. Helped raise the money for Salvador, Platoon and The Terminator.

people and I love it. Good beer, beautiful women, cheap rent. What more do you want in life?

Oliver Stone: Richard Boyle was a friend of mine. He was always fun for a couple of laughs. He had a manuscript of short stories and incidents that had occurred in El Salvador. He pulled it out of the back seat of his car one day on the way to airport. He said; ‘You never know: there might be something there.’ I read it and I said; ‘This is it: this is the greatest story!’

Elizabeth Stone: Right after [Stone’s eldest son] Sean was born, Oliver put our house in New York on the block to get the money to shoot Salvador.

“El Salvador is a great place with great people and I love it. Good beer, beautiful women, cheap rent. What more do you want in life?”

Oliver Stone: Richard was staying at my house. Elizabeth wanted me to get him out of the house. One morning we woke up and he’d passed out in front of the TV. Elizabeth went to the kitchen and opened the refrigerator and everything was gone, everything had been drunk, even the baby’s formula was missing. She went back and looked at him and he was holding the baby’s formula. He’d drunk the whole fucking thing. He must’ve been blind drunk and just grabbed whatever was in the can.

Richard Boyle: Who doesn’t enjoy a drink?

Oliver Stone: The original idea was to shoot a semi-documentary in El Salvador starring Boyle as himself and Dr Rock as himself and we were going to get the Salvadorians to put up all their military equipment. Boyle took me down to El Salvador and we partied.

Richard Boyle: We met with [Robert] D’Abusisson’s generals. They liked Oliver because they loved Scarface.

Oliver Stone: These guys were slapping us on the back, drinking toasts to [Scarface’s] Tony Montana. They kept talking about their favourite scenes and acting out the killings. They’d go; ‘Tony Montana, mucho cajones [Lots of balls)! Ratta-tat-tat! Kill the fucking communists!’

Richard Boyle: It would have been great to make the movie in El Salvador, spend some hard currency, help the people out. But then people started dying so we had to think again.

Gerald Green: Oliver went to great lengths to explain that the film wasn’t going to be another Year Of Living Dangerously or Under Fire. I think that pleased everybody.

Oliver Stone: The problem with characters like Sidney Schanberg in The Killing Fields is that they were heroic characters. I found it a bit movie-ish that they no personal flaws. They were dignified, they were liberal and they were noble, whereas Richard Boyle is more of a second-rate with many personal flaws. I liked him because he was a gadfly. He’s such an irritating personality, but he does have this ability to get under your skin. And that’s the kind of character I wanted to do.

James Woods: Hollywood wasn’t hot on the idea of Salvador, but Oliver was: red hot.

Oliver Stone: I intended to make the movie by hook or by crook. I knew up front that Salvador was going to be a very hard sell. I felt we would have to do it independently as best we could. But it was worth it to do it that way, because we were free and we shot a script that no American studio would ever have allowed to be shot. And John Daly, a delightful kind of British rascal, made it easier, as did Gerald Green. Daly saw these two scuzzbags, Boyle and Dr Rock, as funny, almost in Monty Python-esque terms. And Gerald had some tax deal where if he could make his movies in Mexico, he could get them financed. Gerald had this Arnold Schwarzenegger project called Outpost, and Schwarezenegger couldn’t fulfil his obligations, so all during shooting we were called Outpost because we had that slot.

James Woods: I’d heard of Oliver as being this crazy, druggy, gifted writer. I liked him right away. His reputation preceded him, bolstered I have to say by Oliver’s own efforts: he was very good at getting himself in the headlines of people’s minds. But he was never afraid to be who he was.

Oliver Stone: I had very good luck with the script. It was easy to cast. I was just amazed by the co-operation I got from the actors, all of them. In any film, that kind of co-operation is always welcome. In Salvador, it was almost a necessity.

Michael Murphy: Originally, Oliver talked about Richard playing himself but I don’t think that was ever a serious consideration. And besides Boyle didn’t play Boyle as well as James Woods played him.

“Richard was staying at my house. One morning we woke up and he’d passed out in front of the TV, everything had been drunk, even the baby’s formula was missing. He must’ve been blind drunk and just grabbed whatever was in the can.”

James Woods: Oliver wanted me to play Dr Rock but when I read the screenplay, I got excited about the idea of playing the lead because it was such a great role.

Oliver Stone: Richard is much worse than Jimmy. Richard’s a very colourful character. Jimmy didn’t want to play him as raggedy and scummy as Richard really is. Jimmy felt he made Richard more attractive to a larger group of people. People say; ‘That’s attractive?!’ But the real Richard is far worse.

Richard Boyle: So much of this movie’s real. I’m real, Dr Rock’s real, my girlfriend’s real. Major Max is real – we changed his name but he’s real. (The real character-bad character at that—was the arch criminal CIA-connected Col. D’Aubuisson.)

John Savage: My character was based on the photo-journalist John Hoagland. I have a line in the film about capturing the nobility of human suffering and death in these tragic situations. That’s what Cassady’s trying to do.

Oliver Stone: Dr Rock, Boyle’s companion in the film, was a real guy, but he never went to Salvador. I said; ‘Let’s take him to Salvador then and see what happens.’ Take this character who’s freaked out by anything and put him there. And that became the key to making the movie work.

James Belushi: Dr Rock’s a wonderful character – a genuine ’60s throwback. To me, it was like creating a totally fictional character. He was ignorant of Central American issues like most of the American public, so I feel like I was a touchstone for the audience. My character discovers El Salvador as the audience does.

Oliver Stone: I had to do this movie fast because I never knew when the money would dry up.

Gerald Green: It was the toughest movie I’ve made in my life. I’ve done pictures far bigger. We were the co-production company for Dune and that movie was easy compared to Salvador.

James Woods: We were all just nuts. I don’t know why we were nuts but I think it was in the nature of the picture. I’m playing this lunatic and we’re riding fucking burros up in the woods. John Savage is a brilliant, unheralded, unappreciated nutcase great actor. Oliver is a fucking lunatic.

James Belushi: I like Jimmy [Woods] and all but he always has to have the last word in a scene. He would improvise things to call attention to himself. There was this scene where I was explaining some things I felt were pretty important and right in the middle of my fucking speech, Jimmy pulls out a switchblade and clicks it open right into the camera. So they have to cut over to him for a close-up during my speech. I told Jimmy; ‘If you pull that knife again in one of my scenes, I’m going to open the goddamn glove compartment and pull out a gun and start waving it around.’

James Woods: With Jim Belushi, I didn’t know him at all beforehand and we took an instant liking to each other.

James Belushi: There’s a scene where we come out of this armoured personnel carrier and get into the back of an open truck. So Oliver says; ‘Jim Belushi, you come out first and walk in front with your hands over your head and get into the truck, and then Jimmy Woods, you come walking right behind him.’ So we get out and start to walk, and Jimmy literally knocks my arm out of the way, and sort of elbows his way in front of me, and we get into he truck and I’m pissed and Jimmy won’t shut up. He’s improvising all these lines because he knows that as long as he’s talking, the camera has to stay on him. And I finally said; ‘Will you shut up!’ Oliver left it in the movie because it fits, but it’s really just me telling Woods to shut the fuck up!

James Woods: Belushi and I would always tease each other. And the same thing with Savage. I remember when the three of us would be in the same scene, Oliver would say; ‘This will be a struggle to see who’s going to steal the scene.’ But, of course, that situation is what makes for great movie making.

“I intended to make the movie by hook or by crook. I knew up front that Salvador was going to be a very hard sell. I felt we would have to do it independently as best we could.”

Robert Richardson: Jimmy Woods made a decision to go at Oliver, deliberately push him. He pushed Oliver hard, and Oliver ended up pushing back. The two of them just came to that end, ego against ego. As a result, his performance is what it is, and that’s one of the reasons I believe it’s so fine.

Oliver Stone: Jimmy’s like the guy you want to punch out at school, He drove everybody crazy. The crew, me, his fellow actors. Everyone wanted to kill him because we had no money and we really had to depend on his mercy. He was the biggest single star in the entire thing. When someone is always reminding you of that, it becomes tiresome.

James Woods: Oliver and I are great friends now, and were then, but there was a lot of tension between us during the making of the film. At one point, I was strapped down to the street with these squibs running up my legs because I was supposed to get shot, and this Mexican pilot was about to fly this old plane real low right over me. Just before the scene starts, I hear Oliver say; ‘God, I miss combat.’ So I think; ‘You get down here and be wired to the damn street with his screwy plane flying over you then! ‘

John Savage: We teased each other, we played practical jokes on one another. A lot of the time, we did it because we were bored or restless. We were never really nasty to each other but we did take it too far sometimes. I remember, one time, we really pissed off Jimmy Woods and he left the set. He just got up and headed to the airport on foot!

James Woods: I’d got so pissed off with Oliver and John, I left the set. So, I’m in the middle of nowhere in Mexico and I’m hitchhiking. None of the trucks are stopping. I’m going; ‘Why the fuck aren’t they stopping?’ What I don’t realise is that Oliver is at the head of the road waving down the cars, saying; ‘There’s a crazy gringo with a .45. Don’t pick him up because he’ll shoot you!’

Michael Murphy: Jimmy Woods is a great, great actor. That incredible confession scene, that whole scene came straight out of his head.

James Woods: I remember the day we were shooting the Romero assassination scene at the church and Oliver said; ‘Maybe you should do a confession.’ And I said; ‘Oh, really?’ So I asked for the lines, but he said; ‘I don’t want to give you lines. I want you to just look into that dark murky soul of yours and come up with whatever you want. And I said; ‘Okay, fair enough.’ We didn’t even do a rehearsal. What you saw was the first time it came out of my mouth. When I got done, Oliver said; ‘It’s frightening the shit that you think of.’

Oliver Stone: We ran out of funds in Mexico. We had to struggle for every dollar.

Robert Richardson: The crew was union and if you didn’t pay them on time each week, they wouldn’t work. There was a feeling that each day would be our last. Perhaps Oliver drew inspiration from the uncertainty.

Oliver Stone: It was a complicated scam, getting the movie finished. It involved acts of high piracy, buccaneering and skulduggery.

James Woods: One time I got a phone call through to my agent and he said; ‘You haven’t been paid for two weeks so come home.’ And I said; ‘I’m not going to do that to Oliver. Tomorrow’s our biggest day.’ He said they were going to fuck me so I should split.

Oliver Stone: We took over this entire town for a week to shoot the battle of Santa Ana. The mayor was great. He loved movies. We redesigned his office and used it as a whorehouse set, with real prostitutes. He liked the decor so much he kept it that way, red walls and all. Later, he said; ‘Go ahead, blow up the whole fucking City Hall,’ and we blew it to pieces.

James Belushi: We were shooting the battle and Oliver got the idea of having these rebel troops riding in on horseback and charging the tanks. There wasn’t any money in the budget. But Oliver wanted that fucking cavalry. Gerald Green’s saying; ‘We don’t have the money.’ And Oliver says; ‘Then take my salary. I’ve got $25,000 coming, take that and get those fucking horses.’ He didn’t care about the money.

Oliver Stone: I always feel like a little bit of me dies when I finish a movie.

James Woods: The film was over. Oliver just sat down on the curb. He had this kind of stunned look, amazed that he’d actually managed to finish the picture. I sat down beside him. I said; ‘You know what? I think you made a great film. And all this stuff I fought about was because I really wanted this film to be like no other.’ And he said; ‘Yeah, everything we did made it better.’

Oliver Stone: We had tremendous battles in the editing room. Daly and I fought on everything. There were moments that were really bristly where I felt like he was going to throw me out.

“We were all just nuts. I’m playing this lunatic and we’re riding fucking burros up in the woods. John Savage is a brilliant, unheralded, unappreciated nutcase great actor. Oliver is a fucking lunatic.”

John Daly: Oliver puts 1000% of himself into a film. It’s all up on the screen. For Salvador, he waived his salary and expenses. I think he would have given up his house. I don’t think he goes and directs a film. I think he lives a film. It’s a rare quality.

Oliver Stone: The feeling was that people in America didn’t know how they were supposed to react to the movie which I found kind of sad. Dr Strangelove was a perfect amalgam of humour and seriousness about a subject that is extremely dark. There’s no reason the subject of Salvadoran death squads has to be solemn.

James Woods: I saw the final cut of the film. I watched it with the music for the first time. All of a sudden I thought; ‘My God: I thought it was this little movie. Am I wrong or is this a Great Movie?’ Bob Dylan was there and said; ‘This is the greatest movie I’ve ever seen.’

Oliver Stone: The reviews from the liberal press were often sympathetic, but there was what I call a ‘smothering blanket’ reaction from the conservative press where they don’t take you on, they don’t engage you, they simply ignore you. ‘Time’ completely ignored the movie: it was as if it didn’t exist.

John Savage: Salvador got incredibly mixed reviews. The people that liked it really liked it. But there was a lot of talk about whether Oliver was a communist and whether he loved America and, if he didn’t, why he didn’t just leave and go and live in El Salvador. (The brainwash at work. The idea that our filthy foreign policy represents us.—Eds.)

Oliver Stone: The only reason the picture survived was the video revolution. Salvador did very well on video. People started talking about it and it got nominated for two Oscars, for Best Screenplay and Best Actor. That wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t for video.

John Daly: Salvador is a great film. If it had come out after Platoon, it would have had a completely different reception.

Oliver Stone: I worked without pay for a year, but it was worth every single moment of it. It was a tough movie to make, but it has an edge, it has a madness and it has an anarchy, which is good.

James Woods: People always see things from their own point-of-view. The reason I like Salvador is because it shows all sides just as they happened.

Oliver Stone: We were against such odds. I had so many roadblocks to make that picture. And I got enough of what I wanted in there. We shot Salvador the way it looks – hand-held, urgent – I love that movie. It was an ugly duckling. It went after American policy in Central America and it said some things Americans didn’t want to hear.