The Revolution Will Not Be Televised…Nor Will It Be Brought To You By Russell Brand, Oliver Stone Or Noam Chomsky

THIS IS A REPOST • FIRST PUBLISHED NOV 10, 2013

THIS IS A REPOST • FIRST PUBLISHED NOV 10, 2013

what's left

By Stephen Gowans

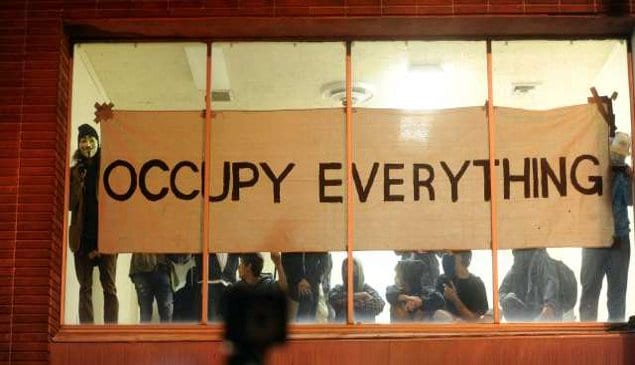

Lacking a central organizing idea and concrete vision of where they wanted to go, spontaneous movements like Occupy were too hobbled by anarchist nonsense to achieve much more than to sell a few more copies of Z Magazine and to create a decent phrase about the 1% making off with all the wealth at the expense of the 99%.

Not too many years ago, when protesters were running riot through the streets, disrupting meetings of the WTO, G7, and other international organizations, the Canadian newspaper The National Post served up a flattering and generous portrait of young people who had eschewed the streets as a terrain for political struggle and turned instead to what the newspaper considered the responsible and laudatory path of seeking nomination to run as candidates for the mildly social democratic (but in the newspaper’s view, rabidly leftwing) New Democratic Party.

This was a curious turn of events, for the National Post, a newspaper founded by the notoriously rightwing, white-collar criminal, Lord Conrad Black, was as likely in normal times to heap praise on anyone associated with the NDP as George Bush was to sing the praises of Kim Il Sung. But these were not normal times. In retrospect it’s easy to see that the protests, demonstrations, and strikes of the time, would fizzle and die, as the Occupy movement would also fizzle and die years later. Lacking a central organizing idea and concrete vision of where they wanted to go, they were too hobbled by anarchist nonsense to achieve much more than to sell a few more copies of Z Magazine and to create a decent phrase about the 1% making off with all the wealth at the expense of the 99%. But it was clear that the editors of the National Post were worried enough to recommend a path other than the streets to those who burned with the desire for political change. That they should recommend electoral politics was predictable. Young people who plowed their energies into the NDP would soon get bogged down in the harmless, ineffectual, routines of political campaigns, and be kept safely off the streets.

The wealthy are keen on electoral politics—when they go their way, as they often do. Elections in capitalist society can be dominated by money, as can the larger political process. Banks, corporations and major investors lobby politicians, fund political campaigns, bribe legislators with the promise of lucrative post-political jobs, place their representatives in key positions in the state, and shape the ideological environment through their control of the media, creation of think-tanks, hiring of PR firms, and funding of university chairs. Those without wealth can hardly compete, except, in principle, by pooling their resources and hoping to tilt the balance the other way against a formidable foe that controls infinitely more resources. The absence of organization and class consciousness, however, routinely assures this doesn’t happen. Moreover, the electoral arena channels dissent into predictable, controllable paths, keeping it off the streets, where it might become unpredictable and therefore dangerous. Additionally, the sway that corporate, banking and investor groups exercise behind the scenes is masked by the egalitarian spectacle of elections. One person, one vote. What could be more equal?

The wealthy are keen on electoral politics—when they go their way, as they often do. Elections in capitalist society can be dominated by money, as can the larger political process. Banks, corporations and major investors lobby politicians, fund political campaigns, bribe legislators with the promise of lucrative post-political jobs, place their representatives in key positions in the state, and shape the ideological environment through their control of the media, creation of think-tanks, hiring of PR firms, and funding of university chairs. Those without wealth can hardly compete, except, in principle, by pooling their resources and hoping to tilt the balance the other way against a formidable foe that controls infinitely more resources. The absence of organization and class consciousness, however, routinely assures this doesn’t happen. Moreover, the electoral arena channels dissent into predictable, controllable paths, keeping it off the streets, where it might become unpredictable and therefore dangerous. Additionally, the sway that corporate, banking and investor groups exercise behind the scenes is masked by the egalitarian spectacle of elections. One person, one vote. What could be more equal?

I was reminded of this after reading the Russell Brand-edited issue of The New Statesman [1], not because it was in any particular way an endorsement of capitalist democracy, but because, like the National Post, it defined legitimate political change within parameters favorable to the established order. Of course, Brand wasn’t advocating electoral politics as the National Post was. On the contrary, he spoke out against voting in an interview with the BBC’s Jeremy Paxman, and called for a revolution. But Brand’s New Statesman went further than the National Post. Where the National Post said that those who fight for political change within the established system are admirable, while those who step outside it are not, Brand, as editor, tackled the larger idea of revolution (the only way, he said, he could get interested in politics. ) Mind you, a mass-circulation magazine was not about to become a platform to rally the masses to armed insurrection to overthrow the established order. “The revolution,” observed Gil Scott-Heron, “will not be televised.” Nor will it be found in the pages of the New Statesman. Predictably, the outcome of Brand’s editing exercise was the redefining of the entire idea of revolution, or, I should say, the destroying of it altogether, turning it into something vague and difficult to put your finger on, except to say it was good, and true, and safe to bring home to mother. But not at all like what Lenin, Stalin, Mao and Kim Il sung were implicated in. According to the luminaries Brand assembled to hold forth on what revolution means, revolution isn’t the transfer of productive property from one group to another –from, say, private owners to workers, or colonial settlers to those they dispossessed, or even owners who reside outside a country to the people within. Instead, it means many things, but not what you thought it did. [2]

In Brand’s issue of The New Statesman, film-maker Judd Apatow writes that revolution is telling authority figures to fuck off…in a funny way. “Comedy itself is revolutionary,” he says, whatever that means. Deepak Chopra rejects politics altogether as “irrelevant” and writes that he puts his “trust in inner revolution,” as priests and other religious figures have done for centuries, counselling the exploited to look inward rather than outward, leaving the exploiters to carry on exploiting free from the inconvenience of anyone fighting back. Comedian Francesca Martinez seeks, not a revolution in who owns productive property, but “of our ideas.” Author Howard Marks begins on a promising note, writing that he would like to see a revolution along the lines of the “Marxist notions of transferring power from reactionary to progressive classes,” but quickly plunges into the ridiculous by expressing the hope that such a revolution will create an immediate utopia, where we can all smoke dope, love each other, and never fight. The model he would like to see realized on a grand scale is the “wine-drinking, dancing, pagan society without a written language” of the Kalash Valleys in northern Pakistan. “There are no prisons, no laws, no police and no vested interests.” Tim Street, director of UK Uncut Legal Action calls “democracy” the most revolutionary idea, and offers a vision of revolution in which the corporate ruling class remains in place (hence, no revolution at all), but where the people try to hold it in check. Street writes, “we can begin by holding corporations which put profit before people to account and fight back when they bully and threaten us. We can begin by using our voices and our bodies to protest, to take direct action against the cuts and tax dodging.” How depressingly far the idea of revolution has drifted (or has been pushed) from its moorings, when anti-capitalist revolution once meant abolition of the profit system, not pressuring corporations to put people before profits (a Quixotic project, since it is both legally and systemically impossible for capitalism to put people before profits. Street has set a rather ambitious goal for himself if he thinks he’s going to hold all the corporations that put profits before people (i.e., all of them) to account. He’ll hardly have time to keep abreast of the latest Noam Chomsky interviews on YouTube.) Newspaper owner Evgeny Lebedev offers nothing better, but at least knows what a revolution is, pointing to the American, French and Russian revolutions as revolutions. But Lebedev’s view of these revolutions is precisely what you might expect of a business owner. The American Revolution, he says, was “mostly very good”. The French is to be applauded, in part. But the Bolshevik revolution had no redeeming features whatever, expect this: It showed “that Marx’s method was incompatible with freedom and dignity.” Lebedev endorses “evolution” as “the better guide to human affairs” (now that the bourgeois revolutions have succeeded.) [3]

In Brand’s issue of The New Statesman, film-maker Judd Apatow writes that revolution is telling authority figures to fuck off…in a funny way. “Comedy itself is revolutionary,” he says, whatever that means. Deepak Chopra rejects politics altogether as “irrelevant” and writes that he puts his “trust in inner revolution,” as priests and other religious figures have done for centuries, counselling the exploited to look inward rather than outward, leaving the exploiters to carry on exploiting free from the inconvenience of anyone fighting back. Comedian Francesca Martinez seeks, not a revolution in who owns productive property, but “of our ideas.” Author Howard Marks begins on a promising note, writing that he would like to see a revolution along the lines of the “Marxist notions of transferring power from reactionary to progressive classes,” but quickly plunges into the ridiculous by expressing the hope that such a revolution will create an immediate utopia, where we can all smoke dope, love each other, and never fight. The model he would like to see realized on a grand scale is the “wine-drinking, dancing, pagan society without a written language” of the Kalash Valleys in northern Pakistan. “There are no prisons, no laws, no police and no vested interests.” Tim Street, director of UK Uncut Legal Action calls “democracy” the most revolutionary idea, and offers a vision of revolution in which the corporate ruling class remains in place (hence, no revolution at all), but where the people try to hold it in check. Street writes, “we can begin by holding corporations which put profit before people to account and fight back when they bully and threaten us. We can begin by using our voices and our bodies to protest, to take direct action against the cuts and tax dodging.” How depressingly far the idea of revolution has drifted (or has been pushed) from its moorings, when anti-capitalist revolution once meant abolition of the profit system, not pressuring corporations to put people before profits (a Quixotic project, since it is both legally and systemically impossible for capitalism to put people before profits. Street has set a rather ambitious goal for himself if he thinks he’s going to hold all the corporations that put profits before people (i.e., all of them) to account. He’ll hardly have time to keep abreast of the latest Noam Chomsky interviews on YouTube.) Newspaper owner Evgeny Lebedev offers nothing better, but at least knows what a revolution is, pointing to the American, French and Russian revolutions as revolutions. But Lebedev’s view of these revolutions is precisely what you might expect of a business owner. The American Revolution, he says, was “mostly very good”. The French is to be applauded, in part. But the Bolshevik revolution had no redeeming features whatever, expect this: It showed “that Marx’s method was incompatible with freedom and dignity.” Lebedev endorses “evolution” as “the better guide to human affairs” (now that the bourgeois revolutions have succeeded.) [3]

Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick, authors of The Untold History of the United States, offer a 1960s New Left anarchist vision, where the only good revolutions are the ones that never happened and the bad ones are the ones that did. This meshes well with a brief entry by anarchist Noam Chomsky on how utopia can be brought about (about which more in a moment.) Stone and Kuznick find inspiration in former US Vice President Henry Wallace’s idea of a worldwide people’s revolution, which would “end militarism, imperialism and economic exploitation, redistribute wealth on a global scale, and spread the fruits of science and industry.” Great, but there are two problems here. For Stone and Kuznick, who, by the way, make no apologies for engaging in utopian (i.e., unrealistic) thinking, revolution is the answer to an intellectual problem: how to eliminate militarism, imperialism, and exploitation, which they regard as morally insupportable. But revolutions don’t work that way. People don’t overturn an existing political and economic order because they dislike militarism intellectually or regard exploitation as morally indefensible. They overturn existing orders when the conditions of their lives become intolerable, and revolution becomes the only way out—which is more likely to happen in the countries which are the victims of militarism and imperialism than in the ones which are the perpetrators and within whose borders lie the audience Stone’s and Kuznick’s comments are presumably directed at. Secondly, the duo seems to want to arrive at utopia without violence, conflict, hierarchy or power politics—in other words, a utopian path to utopia, where a utopia must first exist before it can be realized. We “have too often seen the use of violence unleash emotions and forces that beget more violence and new forms of tyranny and oppression,” they write. [4]

Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick, authors of The Untold History of the United States, offer a 1960s New Left anarchist vision, where the only good revolutions are the ones that never happened and the bad ones are the ones that did. This meshes well with a brief entry by anarchist Noam Chomsky on how utopia can be brought about (about which more in a moment.) Stone and Kuznick find inspiration in former US Vice President Henry Wallace’s idea of a worldwide people’s revolution, which would “end militarism, imperialism and economic exploitation, redistribute wealth on a global scale, and spread the fruits of science and industry.” Great, but there are two problems here. For Stone and Kuznick, who, by the way, make no apologies for engaging in utopian (i.e., unrealistic) thinking, revolution is the answer to an intellectual problem: how to eliminate militarism, imperialism, and exploitation, which they regard as morally insupportable. But revolutions don’t work that way. People don’t overturn an existing political and economic order because they dislike militarism intellectually or regard exploitation as morally indefensible. They overturn existing orders when the conditions of their lives become intolerable, and revolution becomes the only way out—which is more likely to happen in the countries which are the victims of militarism and imperialism than in the ones which are the perpetrators and within whose borders lie the audience Stone’s and Kuznick’s comments are presumably directed at. Secondly, the duo seems to want to arrive at utopia without violence, conflict, hierarchy or power politics—in other words, a utopian path to utopia, where a utopia must first exist before it can be realized. We “have too often seen the use of violence unleash emotions and forces that beget more violence and new forms of tyranny and oppression,” they write. [4]

It was the New Left’s desire for the ocean without the roar of the river that led to the movement’s denunciation by its critics as comprising those who “combine the luxury of being eternally in the right without the obligation of ever actually being responsible for anything.” And indeed, the New Left, and its successors, managed to escape responsibility by never actually achieving anything that would require that they bear it. Arnold Kettle noted in 1960, that “What the New Left seems not to be able to stomach is that (the countries that actually had revolutions) should have not only principles but also a strategy, a diplomacy, a defense policy…and all the responsibilities and consequent impurities… Power politics is always used by New Left writers in a derogatory sense, as if there were some other form of politics.” As for the New Left vision of what a revolution was to achieve, “it was a reality beyond class struggle, a society which is neither capitalist nor socialist, but simply nice.” [5] Indeed, Stone and Kuznick express their vision in terms of a nice world of “creativity, kindness and generosity” where “greed and the lust for power” have no place, rather than a world of jobs for all, free heath care and education, cheap public transportation, subsidized housing, and affordable childcare, racial and gender equality, and investment of the social surplus into raising the living standards of all. If you want a nice world of kindness and charity where greed and lust for power have no place, there are plenty of religions around to take care of that. But that’s not revolution.

Stone and Kuznick reserve special scorn for” Stalin, Mao and the Kims”, who they depict as power-hungry defilers of “the noble concept of revolution” who grabbed power to aggrandize themselves. Fuck them, they write. One day someone will have to write The Untold History of 20th Century Revolutions to correct Stone’s and Kuznick’s defiling of accomplished revolutionaries. For now, suffice to say that the title of the duo’s book ought to be changed to The Untold History of the United States by Two Confused Leftists Who Have Yet to Be Told the Untold History of Russia, China and Korea.

For Stone’s and Kuznick’s benefit here’s a brief history to fill the gaps of their knowledge.

Kim

Kim Il Sung was an effective guerrilla leader who made an enormous contribution to the liberation of Korea from Japanese colonial rule, and from the form of residual rule by Japanese collaborators that took hold in the south, and has echoes today. South Korea’s current president, Park Geun-hye, is the daughter of the military dictator, Park Chung-hee, who served in the Japanese imperial army, hunting down Kim and his guerrillas. Whatever one might say about the de facto, but hardly de jure, Kim dynastic succession, the Kims trace their lineage to a leading anti-colonial guerrilla who played a lead role in building an independent state, free from domination by outside powers. The south, in contrast, is a neo-colony of the United States, where the armed forces are under the wartime command of the Pentagon, and anti-communist descendants of Japanese collaborators exercise local control. Had Kim anticipated Deepak Chopra’s path and declared politics “irrelevant” and put his “trust in inner revolution”, Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick might have lauded him, rather than blurting “Fuck…the Kims.” Yet, the price of Kim’s earning the respect of the New Left film-makers would likely have been Korea remaining a colony of Japan, or more likely, a neo-colony of the United States from the south to the north.

Mao

Before the Mao-led revolution in China, 55 to 65 percent of the land was owned by 10 percent of the population, mainly landlords–parasites who exploited the labor of peasants by virtue of claiming ownership of the land and holding it by law and force. Hundreds of millions eked out bare existences on tiny plots and forever faced the threat of famine. The country had less industrial power than Belgium. Long dominated by outside powers, the Chinese lived as untermenschen in their own country. “Everything fed the revolution. Only by revolution could China’s peasants get land, get out from under landlord control…Without revolution, China would have remained in the grip of imperialism, a semi-colony, dominated and exploited by the United States.” [6] Domenico Losurdo points out that, “It is widely known that Mao Zedong declared at the foundation of the Peoples Republic of China that the Chinese nation had risen up and nobody would tread on it again. Perhaps he was thinking about the years when a sign at the entrance to the French consulate in Shanghai forbade entrance to Chinese and dogs.” Losurdo asks: “Is the new situation in the great Asian country a result of ‘failure’?” [7] To be sure, the Chinese Revolution falls well short of Stone’s and Kuznick’s vision of a world free from militarism, imperialism, and exploitation, and where creativity, kindness, and generosity have replaced greed and lust for power, but it did improve the lives of hundreds of millions. As the privileged son of a stockbroker who has lived his life in a country that dominates others, Stone may regard Mao’s revolution as a defiling of the noble concept of revolution, but he’d find few Chinese to agree with him.

Stalin

Stalin made enormous contributions to socialism, decolonization, and indirectly, to the emergence of the welfare state in the West. He played a lead role in the building of the first publicly-owned, planned, economy –one free from unemployment and the insecurities and injustices of the past. He was at the forefront of the project to lift Russia from backwardness, succeeding spectacularly in short order. His contributions to the defeat of fascism were unparalleled, exceeding those of any other individual. Under his leadership, the monarchies and military dictatorships of Eastern Europe were overthrown and, no, the socialist societies that replaced them were not simply new forms of oppression. Their economies grew rapidly and with them standards of living rose to unprecedented levels, while the insecurities, injustices, inequalities and exploitation of the past were eliminated. The national liberation movement had no greater friend than Stalin’s Soviet Union. By successfully creating an alternative to capitalism, Stalin forced Western governments to build robust programs of social welfare to maintain the allegiance of their populations. And the Soviet Union’s policy of racial equality embarrassed the United States into improving the conditions of its black citizens.

Stalin made enormous contributions to socialism, decolonization, and indirectly, to the emergence of the welfare state in the West. He played a lead role in the building of the first publicly-owned, planned, economy –one free from unemployment and the insecurities and injustices of the past. He was at the forefront of the project to lift Russia from backwardness, succeeding spectacularly in short order. His contributions to the defeat of fascism were unparalleled, exceeding those of any other individual. Under his leadership, the monarchies and military dictatorships of Eastern Europe were overthrown and, no, the socialist societies that replaced them were not simply new forms of oppression. Their economies grew rapidly and with them standards of living rose to unprecedented levels, while the insecurities, injustices, inequalities and exploitation of the past were eliminated. The national liberation movement had no greater friend than Stalin’s Soviet Union. By successfully creating an alternative to capitalism, Stalin forced Western governments to build robust programs of social welfare to maintain the allegiance of their populations. And the Soviet Union’s policy of racial equality embarrassed the United States into improving the conditions of its black citizens.

It’s instructive to consider the Soviet Union in 1936. Soviet democracy, based on the constitution Stalin played a key role in writing, was being rolled out. The constitution mandated the creation of a system of elected representatives. Stalin was elected the representative of a Moscow constituency of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. By this assembly he was elected as one of 30 members of the Presidium, which in turn elected a Council of Commissars. He did not call himself a dictator, nor was there a position of dictator to be occupied.

Soviet democracy has been derided and ridiculed in the West. But let’s consider the Soviet form of democracy in 1936 versus the Western form. At the time, Britain had an unelected House of Lords (still does), while Canada had, and continues to have, an unelected Senate. Of 500 million inhabitants of the British Empire, only 70 million, or 1/7th, lived in political democracies. South Africa denied suffrage to its black population. In Canada and Australia, aboriginal people were not allowed to vote. India had no political democracy at all, and was governed by the British civil service. The United States denied civil rights to its black citizens, who lived in a state of oppression. [8] In contrast, suffrage in the USSR was universal, hardly the tyranny by comparison with the West that Stone and Kuznick would have us believe it was.

As to the perennial charge that Stalin murdered millions, we can dismiss this as an unexamined legend that everyone believes to be true because someone (they just can’t remember who) told them it was, and about which they can provide no details, like who, how, when and why? William Blum writes:

“We’ve all heard the figures many times…10 million…20 million…40 million…60 million…died under Stalin. But what does the number mean, whichever number you choose? Of course many people died under Stalin, many people died under Roosevelt….Dying appears to be a natural phenomenon in every country. The question is how did those people die under Stalin? Did they die from the famines that plagued the USSR in the 1920s and 30s? Did the Bolsheviks deliberately create those famines? How? Why? More people certainly died in India in the 20th century from famines than in the Soviet Union, but no one accuses India of the mass murder of its own citizens. Did the millions die from disease in an age before antibiotics? In prison? From what causes? People die in prison in the United States on a regular basis. Were millions actually murdered in cold blood? If so, how? How many were criminals executed for non-political crimes? The logistics of murdering tens of millions of people is daunting.” [9]

The numbers are, in fact, estimates derived by comparing the Soviet population with projections of whatever the author making the estimate thinks the population would have been at a given point had Stalin never existed. The difference between the two figures is then said to represent the missing population, or people Stalin “murdered.” It’s obvious that this method is open to abuse and that attributing excess deaths to mass murder has no other intention than to bamboozle people into believing that Stalin ordered the cold-blooded killing of tens of millions. This isn’t to say that Stalin didn’t order executions, and lots of them. He did. But executions in times of exceptional circumstances, when the revolution was under threat from within and without—as the Soviet Union was throughout the Stalin era–are no less necessary than the killing of soldiers of an invading army. It was war. Unless action fitting to war was taken, the revolution would fail. Everywhere fifth columnists facilitated the Nazi invasions, except in the Soviet Union where there was no fifth column. Stalin had eliminated it. He may have uniquely accomplished this feat by accepting a high false-positive rate as the cost of extirpating the disease, catching the innocent and harmless in his net as well as the dangerous and guilty. But when it’s unclear whether the tissue is diseased or healthy, the surgeon who saves the patient cuts out both the clearly diseased and the surrounding suspicious (though possibly healthy) tissue. The question is: Did Stalin order executions to satisfy a personal lust for power, or to safeguard the revolution bequeathed by Lenin? Stalin’s political enemies have always favored the first explanation. And the CIA has ensured that those who favored it had a platform from which to spread it far and wide.

When Stalin came to power, the Soviet Union was in a precarious position—its agriculture backward, its industry stunted, its military feeble. What’s more, fierce and fissiparous debate within the Communist Party about the way forward had produced paralysis, infighting and intrigues. The country was going nowhere, fast. Three decades later Stalin was dead. But in those three decades, with Stalin at the helm, the country had advanced from the wooden plow to the atomic pile.

“When Stalin died in 1953, the Soviet Union was the second greatest industrial, scientific, and military power in the world and showed clear signs of moving to overtake the United States in all these areas. This was despite the devastating losses it suffered while defeating the fascist powers of Germany, Romania, Hungary and Bulgaria. The various peoples of the U.S.S.R were unified. Starvation and illiteracy were unknown throughout the country. Agriculture was completely collectivized and extremely productive. Preventive health care was the finest in the world, and medical treatment of exceptionally high quality was available free to all citizens. Education at all levels was free. More books were published in the U.S.S.R than in any other country. There was no unemployment.

“Meanwhile, in the rest of the world, not only had the main fascist powers of 1922-1945 been defeated, but the forces of revolution were on the rise everywhere. The Chinese Communist Party had just led one fourth of the world’s population to victory over foreign imperialism and domestic feudalism and capitalism. Half of Korea was socialist…In Vietnam, a strong socialist power, which had already defeated Japanese imperialism, was administering the final blows to the beaten army of the French empire. The monarchies and fascist dictatorships of Eastern Europe had been destroyed by a combination of partisan forces, led by local Communists, and the Soviet Army…The largest political party in both France and Italy was the Communist Party. The national liberation movement among the European colonies and neo-colonies was surging forward…The entire continent of Africa was stirring.” [10]

Were these the accomplishments of a “failed” revolution? Domenico Losurdo demands that critics like Stone and Kuznick,

“explain how a ‘failure’…has managed to make such an enormous contribution to the emancipation of the colonial people and, in the West, to the destruction of the old regime and the emergence of the welfare state. In 1923, when Lenin, gravely ill, is forced to release the reins of power, the state that emerged from the October Revolution, mutilated in the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk, is leading a paltry and precarious life. In 1953, at Stalin’s death, the Soviet Union and the socialist camp are enjoying enormous growth, power, and prestige. A few more of these (‘defilers of the noble concept of revolution’) and the situation of the imperialist and capitalist world system would have become precarious and untenable indeed!” [11]

Contrary to Stone’s and Kuznick’s falsifications, Stalin did more to bring the world closer to their vision of freedom from militarism, imperialism and exploitation than anyone else. Yet the two Americans say “Fuck Stalin.” They don’t, however, say “Fuck Castro.” Why not? The Cuban revolution was guerrilla-led, like Mao’s and Kim’s, assisted by the Soviet Union, like Mao’s and Kim’s, and Cuban socialism is based largely on the “Stalinist” model. Yet, Stone, whose three documentaries on the Cuban revolutionary reveal a soft spot for Castro, doesn’t accuse the leader of the Cuban revolution of defiling the concept of revolution in the interests of power, self-aggrandizement, repression and iron-fisted control.

The inconsistencies don’t stop there. Stone, it seems, also has a soft spot for Barack Obama, who he reportedly voted for in 2008 and 2012. [12] Shouting “Fuck Stalin, Mao and the Kims” while voting for Obama calls to mind Michael Parenti’s criticism of the hypocrisy of left anti-communists who profess revulsion at the “crimes of communism” while facilitating the crimes of Democratic presidents by voting for them.

Parenti explains:

“Under one or another Democratic administration, 120,000 Japanese Americans were torn from their homes and livelihoods and thrown into detention camps; atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki with an enormous loss of innocent life; the FBI was given authority to infiltrate political groups; the Smith Act was used to imprison leaders of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party and later on leaders of the Communist party for their political beliefs; detention camps were established to round up political dissidents in the event of a ‘national emergency’; during the late 1940s and 1950s, eight thousand federal workers were purged from government because of their political association and views, with thousands more in all walks of life witch-hunted out of their careers; the Neutrality Act was used to impose an embargo on the Spanish Republic in favor of Franco’s fascist legions; homicidal counterinsurgency programs were initiated in various Third World countries; and the Vietnam War was pursued and escalated. And for the better part of a century, the Congressional leadership of the Democratic party protected racial segregation and stymied all anti-lynching and fair employment bills. Yet all these crimes, bringing ruination and death to many, have not moved the liberals, the social democrats, and the ‘democratic socialist’ anticommunists to insist repeatedly that we issue blanket condemnation of either the Democratic party or the political system that produced it…” [13]

Stone and Kuznick may deplore these Democratic party crimes, but it’s unlikely they’d ever say “Fuck the Democrats.” It’s more likely they’d say, “Vote Democrat.” So, let’s forget about “Fuck Stalin, Mao and the Kims.” If Stone is really interested in ending militarism, imperialism, and exploitation, why isn’t he telling us to “Fuck Obama,” a major promoter of the scourges Stone says he hates, rather than running down historical figures who actually fought against imperialism and exploitation, and won?

The Stone and Kuznick view is, really, rather quite silly. They believe that Mao and Kim decided to become guerrillas, and Stalin, a Bolshevik, because these were routes to the acquisition of personal power, self-aggrandizement, and iron-fisted control. Yet, at the time, guerrilla and underground revolutionary were hardly the most promising career paths for people who lusted for power and self-aggrandizement. If Stalin really lusted after these things, why didn’t he link up with Tsarist forces, rather than the Bolsheviks, which until mid-1917 were a minor political force that no one (including many Bolsheviks) expected to take power? Chinese and Koreans who became guerrillas were more likely to find themselves dead, tortured or imprisoned, than rising to the head of a bureaucracy administering a new state. They became guerrillas because they found feudal and imperialist oppression intolerable and wanted to put an end to them. A Georgian like Stalin became a Bolshevik because he hated Tsarist oppression and wanted to replace it. Stalin lived much of his early life underground, trying to keep one step ahead of the Tsarist police, and serving long stretches in internal exile. As leader of the Soviet Union he lived a modest, almost Spartan life. He was not a Red Tsar, living in the lap of luxury, as Stone’s and Kuznick’s crude myth-making would have us believe. Stalin, Mao and Kim understood that ending oppression meant taking political power, which meant, in turn, a disciplined, organized approach to the project—one that involved leaders and hierarchy. The idea that the politically-inspired seek power for power’s sake is an anarchist confusion. As Richard Levins points out, even George W. Bush would never have promoted universal free health care, subsidized Venezuela, or renounced Jesus just to stay in power. Behind “every facade of power-hunger, there lurks a person of principles, though (as in Bush’s case) these may be noxious principles.” [14] Revolutionaries seek power to aggrandize the position of the class they represent. People in leadership positions may be in positions to exercise power, but that doesn’t mean they seek power as an end in itself. They seek power as an instrument to accomplish goals that comport with the aspirations of the class or people they represent. Stone’s and Kuznick’s cynicism tars the disciplined, organizational forms necessary for revolution. In their view, and that of anarchists generally, hierarchical, disciplined organizations are vehicles of tyranny and oppression that will inevitably be used by tyrants-in-embryo to catapult themselves to power, whereupon they will subvert the revolution’s beautiful goals to aggrandize themselves and exercise an iron-fisted control. Did Kim subvert the goal of achieving Korean independence? Did Mao not overturn centuries of feudalism and great power domination? Did Stalin fail to abolish unemployment, homelessness, national oppression, and racial inequality? The view that the leaders of successful revolutions betrayed the revolution’s goals to aggrandize themselves is not only bad history, it’s bad politics. It encourages people seeking political change to eschew any form of “Leninist” politics, in favor of “leaderless” agglomerations, which practice decentralized decision-making, and accomplish not much of anything.

Noam Chomsky is an endless source of slurs against Leninism, which he equates with “counterrevolution”, [15] a heterodox view of what revolution is, but certainly consistent with the Brand-edited New Statesman view that it’s something other than what you always thought it was, and what you always thought it was is actually quite a bad thing that should be avoided altogether. I suppose it should come as no surprise that Chomsky answers the question, “What does revolution mean to you?”, with an attack on Lenin, the leader of a revolution that succeeded, and praise for Rosa Luxemburg, a leader of an attempted socialist revolution that failed. Chomsky writes,

“I cannot improve on Rosa Luxemburg’s eloquent critique of Leninist doctrine: a true social revolution requires a ‘spiritual transformation in the masses degraded by centuries of bourgeois class rule…it is only by extirpating the habits of obedience and servility to the last root that the working class can acquire the understanding of a new form of discipline, self-discipline arising from free consent.’ And as part of this ‘spiritual transformation’, a true social revolution will, furthermore create—by the spontaneous activity of the mass of the population—the social forms that enable people to act as free creative individuals, with social bonds replacing social fetters, controlling their own destiny in freedom and solidarity.” [16]

Here’s A.J. Ryder, a historian of the German Revolution, on Luxemburg’s role in the failure to bring about a socialist revolution in Germany in 1918-1919.

“Spartacists (Karl) Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg…were conscious revolutionaries in deed as well as in word. They were bent on using the opportunity presented by the fall of the Hohenzollern regime to set in motion the socialist revolution which they believed would carry them to power in place of Ebert as Lenin had displaced Kerensky….Few (of the leaders) possessed the qualities of a successful revolutionary leader. By common consent Rosa Luxemburg was the outstanding personality of the left, but her intellectual gifts and personal fanaticism were not matched by a grasp of reality. She was at heart a romantic, a visionary appearing in the garb of ‘scientific socialism.’” [17]

Ryder sums up the failure of the revolution by reference to the failings of its key personalities. They “were amateurs compared with Lenin.” [18] Luxemburg, the romantic, emphasized spontaneity and ‘spiritual transformation.’ Lenin, the hard-headed realist, emphasized planning and organization. Luxemburg was murdered by proto-fascist thugs, her bloodied corpse tossed into a canal, as the revolution she sought to midwife, sputtered and failed. Lenin seized power to set in motion a socialist, anti-imperialist project that spanned over seven decades—one that played the key role in exterminating the fascism that, in its embryonic stage, murdered Luxemburg.

Chomsky has enormous respect for those who have failed at revolution, and enormous contempt for those who have succeeded. If we were to follow his lead and emulate the failures, while eschewing the successes, we would be sure to arrive at the same place the National Post wanted young political activists to arrive at: a political dead-end. Brand’s edition of the New Statesman follows in the same vein. Its positive statements are reserved for political action that leaves the established order in place: Chopra’s “internal revolution”; Apatow’s comedy; Lebedev’s evolution; Martinez’s new thinking; Tim Street’s “democracy.” Its negative statements are reserved for the revolutions that actually brought about the “revolutionary transformations of the deepest and most profound sort” that Stone and Kuznick say they want. So, the message is clear. Light a joint, work on your kindness and generosity, demand that corporations put people before profits, watch a Marx Brother’s movie*, and tell Lenin, Stalin, Mao and Kim to fuck off.

*I’ve watched every Marx Brothers' movie, many of them multiple times, but have yet to bring about a revolution."

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Notes

1. New Statesman, October 24, 2013, http://www.newstatesman.com/Russell%20Brand

2. What Does Revolution Mean to You? The New Statesman, October 30, 2013, htt://www.newstatesman.com/2013/10/what-does-revolution-mean-you

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Arnold Kettle, “How new is the ‘NewLeft’”, Marxism Today, October, 1960,http://www.unz.org/Pub/MarxismToday-1960oct-00302

6. Edward and Regula Boorstein. Counterrevolution: U.S. Foreign Policy. International Publishers. 1990. p. 73.

7. Domenico Losurdo, “History of the Communist Movement: Failure, Betrayal, or Learning Process?”, Nature, Society, and Thought, Vol. 16, no 1 (2003). http://homepages.spa.umn.edu/~marquit/nst161a.pdf

8. Sydney and Beatrice Webb. The Truth about Soviet Russia. Nabu Public Domain Reprints. pp. 21-22.

9. William Blum. Freeing the World to Death: Essays on the American Empire. Common Courage Press. 2005. p. 194.

10. Bruce Franklin, “An Introduction to Stalin,” excerpted from Bruce Franklin (Ed.). The Essential Stalin: Major Theoretical Writings, 1905-52 (Anchor Books, 1972). http://anti-imperialism.com/2012/11/02/an-introduction-to-stalin/

11. Losurdo.

12. Solvej Schou, “Oliver Stone on Obama: ‘I hope he wins’”, Entertainment Weekly, November 6, 2012.http://insidemovies.ew.com/2012/11/06/oliver-stone-obama-presidential-election/

14. Richard Levins, “How to Visit a Socialist Country”, Monthly Review, 2010, Volume 61, Issue 11, (April),http://monthlyreview.org/2010/04/01/how-to-visit-a-socialist-country

15. Parenti, pp. 46-47.

16. “What Does Revolution Mean to You?”

17. A.J. Ryder. The German Revolution of 1918: A Study of German Socialism in War and Revolt. Cambridge University Press. 2008. p. 7.

18. Ibid.