State of Fear: How History’s Deadliest Bombing Campaign Created Today’s Crisis in Korea

![]() Special addendum

Special addendum

HOW HOLLYWOOD SOLD US THE (GOOD) KOREAN WAR

PROPAGANDA AS ENTERTAINMENT AN OLD AND POWERFUL TOOL IN MANAGING PUBLIC OPINION

By Patrice Greanville

I

[dropcap]

Bogart apparently felt the change in the air pretty quickly. Some reports say he lashed out at his fellow committee members on the plane home, while other suggest that many members of the brigade booked their own flights home early, out of embarrassment. Certainly, the right wing press—and in this climate, virtually everything save for the Daily Worker was leaning right—started attacking the unfriendly witnesses and their supporters in real time. After Congress voted to indict the Hollywood Ten for contempt, Bogart, allowed a statement to be syndicated to Hearst papers under the headline, “As Bogart Sees It Now,” which read in part:

I am not a Communist sympathizer. … I went to Washington because I thought fellow Americans were being deprived of their Constitutional Rights, and for that that reason alone. That the trip was ill-advised, even foolish, I am very ready to admit. At the time it seemed the thing to do. I have absolutely no use for Communism nor for anyone who who serves that philosophy. I am an American. And very likely, like a good many of the rest of you, sometimes a foolish and impetuous American. (Bogie and the Blacklist, Karina Longworth, Slate, March 4, 2016)

The above is eloquent. Bogie in his virtual recantation equates anti-communism with Americanism, one of the oldest and most fraudulent and cynical equations in the US capitalist propaganda canon. (See American Brainwash: Guess what, Ma, capitalism is not Americanness!).

I offer below a sampler of Korean War movies and television artifacts. I trust the material speaks for itself.

—PG

II

CONTRARIAN REVIEWS

1953 Battle Circus

Bogie (inadvertently) inaugurates the MASH franchise

The film is set in Korea during the Korean War. Bogart plays a surgeon and commander of Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) 8666 (shortened to “66” in the dialogue), with Allyson playing a newly arrived Army nurse (Lieutenant Ruth McGara). Despite their initial handicaps, their love flourishes against a background of war, enemy attacks, death and injury. At first, Ruth is a bumbling addition to the nurse corps, but attracts the attention of the unit’s hard-drinking, no-nonsense chief surgeon Dr. and Major Jed Webbe (Humphrey Bogart). Jed cautions that he wants a “no strings” relationship and Ruth is warned by the other nurses of his womanizing ways. She sees that he is beloved by the unit, especially the resourceful Sergeant Orvil Statt (Keenan Wynn). According to Richard Brooks (in an interview filmed for the 1988 Bacall on Bogart documentary), Battle Circus was originally called MASH 66, a title rejected by MGM because the studio thought people would not understand the connection to a military hospital. The title of the film actually refers to the speed and ease with which a MASH unit, with its assemblage of tents, and portable equipment, can, like a circus, pick up stakes and move to where the action is. The MASH theme, as we know, would re-emerge 20 years later as a television sitcom. Obviously this plot, totally Americanocentric and focused on personal storylines of interest chiefly to American audiences, had little to say about the reasons for the Korean war or our own lethal meddling in the peninsula. (Main source: Wikipedia)

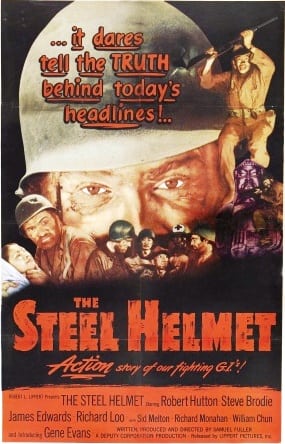

1951 The Steel Helmet

War is tough

This melodrama by writer-director Sam Fuller (the first in the foul crop of Korea-themed movies), could have been about WW2 or WW1, as the story, except for being “localed” in Korea, focuses more on soldierly stuff than the real important historical backdrop. The commies of course are beyond the pale, and, ultimately, flaws and all, American fighting men prove to be the best the world has ever seen. Fuller, a “man’s director” who himself had been a soldier, went on to make a second flick about this war, the very same year, 1951, popular among buffs of this genre, Fix bayonets! In his motion picture debut, James Dean appears briefly at the conclusion of the film. The Steel Helmet was produced by Lippert Studios, founded by a guy who owned about 120 theaters and was fed up with the rental fees he had to pay the big studios. Of some tangential redeeming interest: Racial integration of the U.S. military was going on during the Korean War and the movie is a parable about how all Americans needed to pull together and fight the Cold War. In sum, an ethnocentric film with little to say about the truth of the Korean conflict and with a standard dose of imperial propaganda and opportunistic message about race relations.

This melodrama by writer-director Sam Fuller (the first in the foul crop of Korea-themed movies), could have been about WW2 or WW1, as the story, except for being “localed” in Korea, focuses more on soldierly stuff than the real important historical backdrop. The commies of course are beyond the pale, and, ultimately, flaws and all, American fighting men prove to be the best the world has ever seen. Fuller, a “man’s director” who himself had been a soldier, went on to make a second flick about this war, the very same year, 1951, popular among buffs of this genre, Fix bayonets! In his motion picture debut, James Dean appears briefly at the conclusion of the film. The Steel Helmet was produced by Lippert Studios, founded by a guy who owned about 120 theaters and was fed up with the rental fees he had to pay the big studios. Of some tangential redeeming interest: Racial integration of the U.S. military was going on during the Korean War and the movie is a parable about how all Americans needed to pull together and fight the Cold War. In sum, an ethnocentric film with little to say about the truth of the Korean conflict and with a standard dose of imperial propaganda and opportunistic message about race relations.

1952 Battle Zone

Love triangle gets hot in Korea

Battle Zone is a 1952 Korean War war film. Sequences of the film were shot at Camp Pendleton, California.

Battle Zone is a 1952 Korean War war film. Sequences of the film were shot at Camp Pendleton, California.

A rivalry develops between veteran of World War II M/Sgt Danny Young (John Hodiak) and Sgt. Mitch Turner (Stephen McNally) Marine combat photographers over the attentions of Jeanne (Linda Christian), a Red Cross nurse during the Korean War. Another love triangle between red-blooded guys in uniform and battlefield nurses, again, chiefly concerning Americans. OK, this mess happens to be taking place in Korea, so it’s a war movie about Korea. Knowledge or insight about the conflict: zero. Propaganda value: the usual load.

1954 Prisoner of War

Ronnie’s Noble Sacrifice for the Sake of Victory and Decency in Korea

Has Ronald Reagan ever been involved in any public enterprise not reeking of self-serving jingoistic nonsense? If you’re looking for that don’t look here because in this MGM turkey Ronnie sets new standards for service to the empire and its constant barrage of lies. The plotline says it all and you needn’t sit there for 90 minutes to figure the ending. The story peg is supposedly based on Capt. Robert H. Wise, who lost 90 lbs in a North Korean POW camp. The man served as the film’s technical advisor and said that the torture scenes in the movie were based on actual incidents. The rather ludicrous premise for the film is that an American officer (guess who) volunteers to be captured in order to investigate claims of abuse against American POWs in North Korean camps during the Korean War.

Has Ronald Reagan ever been involved in any public enterprise not reeking of self-serving jingoistic nonsense? If you’re looking for that don’t look here because in this MGM turkey Ronnie sets new standards for service to the empire and its constant barrage of lies. The plotline says it all and you needn’t sit there for 90 minutes to figure the ending. The story peg is supposedly based on Capt. Robert H. Wise, who lost 90 lbs in a North Korean POW camp. The man served as the film’s technical advisor and said that the torture scenes in the movie were based on actual incidents. The rather ludicrous premise for the film is that an American officer (guess who) volunteers to be captured in order to investigate claims of abuse against American POWs in North Korean camps during the Korean War.

For starters, torture when concerning food and pleasant accommodations is a very relative term, especially as understood by Americans, not to mention that, as this article makes clear the conditions in North Korea, thanks to American carpet-bombing and nonstop atrocities had put the entire population on the very edge of barest survival. Expecting to be housed and fed as if he’d been a tourist staying at the local Hilton is pure tendentious and intentionally dumb malarkey, the stuff that Ronnie Reagan thrived in. The Wiki notes that the “release of the film created a minor controversy. “The U.S. Army had assisted production and made edits in the script, but approval was abruptly reversed on the eve of release. The depiction of mistreatment of prisoners complicated the courts martial of POW collaborators that were proceeding at the time.” The Wiki also adds that, in terms of historical accuracy, author Robert J. Lentz of the book Korean War Filmography: 91 English Language Features through 2000 states that the film was “undeniably overstated”.[3]

Expect no truth about North Korea here neither.

1954 The Bridges at Toko-Ri

Glamorizing the genocide in North Korea

The Bridges at Toko-Ri is a 1954 American war film about the Korean War and stars William Holden, Grace Kelly, Fredric March, Mickey Rooney, and Robert Strauss. The film, which was directed by Mark Robson, was produced by Paramount Pictures. Dennis Weaver and Earl Holliman make early screen roles in the motion picture.

The Bridges at Toko-Ri is a 1954 American war film about the Korean War and stars William Holden, Grace Kelly, Fredric March, Mickey Rooney, and Robert Strauss. The film, which was directed by Mark Robson, was produced by Paramount Pictures. Dennis Weaver and Earl Holliman make early screen roles in the motion picture.

The screenplay is based on the novel The Bridges at Toko-Ri by Pulitzer Prize winner James Michener, himself a onetime Navy officer.

Forney (Mickey Roooney) flying his chopper to the rescue wearing his trademark (but non-regulation) Irish top hat.

PLOT: Dashing US Navy Lieutenant Harry Brubaker (William Holden), a fighter-bomber pilot serving on a carrier off the coast of North Korea is given a mission to blast the bridges at Toko-Ri. Holden is not exactly enthused by the idea but his reluctance is not so much motivated by opposition to the war or communist sympathies, just a simple case of self-preservation. Why me? During the attack the commies, always humourless and rude to a fault, have the audacity to shoot Brubaker down behind enemy lines, prompting an attempt at rescue by the movie’s two lovable characters, Chief Petty Officer (NAP) Mike Forney (Mickey Rooney) and Airman (NAC) Nestor Gamidge (Earl Holliman). The boys gallantly try their best to extract Brubaker from his tight spot but the malevolent commies again spoil the fun by blowing up the chopper (a Sikorsky HO3S-1) and killing Nestor. That now leaves Brubaker and Forney hugging a ditch, trying to hold off the enemy with pistols and Forney’s and Gamidge’s M1 carbines until they can be rescued, but both are killed by the North Korean and Red Chinese soldiers. Admiral Tarrant (Fredric March), angered by the news of Brubaker’s death (whom he regarded as a son), demands an explanation from mission Commander Lee of why he attacked the second target. Lee defends his actions, noting that Brubaker was his pilot too, and that despite his loss, the mission was a success. Tarrant, realizing that Lee is correct, rhetorically asks, “Where do we get such men?” At this point there is not a dry eye in the house. Mission indeed accomplished.

1957 Battle Hymn

Pious Rock Hudson battling commies and doing orphan rescue

We sum up this film as a straight highly manipulative propaganda artifact from beginning to end, calculated to touch all the right sentimental buttons in decent people. Heartthrob Rock Hudson is recruited to do his part for the empire and the national religion, “free enterprise” at all costs. Indeed, in Hollywood (and Television) history, few actors have ever escaped that kind of duty, not that they were even remotely aware of what they were doing.

We sum up this film as a straight highly manipulative propaganda artifact from beginning to end, calculated to touch all the right sentimental buttons in decent people. Heartthrob Rock Hudson is recruited to do his part for the empire and the national religion, “free enterprise” at all costs. Indeed, in Hollywood (and Television) history, few actors have ever escaped that kind of duty, not that they were even remotely aware of what they were doing.

Battle Hymn (aka By Faith I Fly) is a 1957 Technicolor war film starring Rock Hudsonas Colonel Dean E. Hess, a real-life United States Air Force fighter pilot in the Korean War. Hess’s autobiography of the same name was published concurrently with the release of the film. He donated his profits from the film and the book to a network of orphanages he helped to establish. The film was directed by Douglas Sirk and produced by Ross Hunter and filmed in CinemaScope. Prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, Dean Hess (Rock Hudson) was a minister in Ohio. The attack prompts him to become a fighter pilot. Hess had accidentally dropped a bomb on an orphanage in Germany during World War II, killing 37 orphans. At the start of the Korean War, Hess volunteers to return to the cockpit and is assigned as the senior USAF advisor/Instructor Pilot to the Republic of Korea Air Force, flying F-51D Mustangs. As Hess and his cadre of USAF instructors train the South Korean pilots, several orphaned war refugees gather at the base. He solicits the aid of two Korean adults, En Soon Yang (Anna Kashfi) and Lun Wa (Philip Ahn), and establishes a shelter for the orphans. When the Communists begin an offensive in the area, Hess evacuates the orphans on foot and then later, after much struggle with higher headquarters, obtains an airlift of USAF cargo aircraft to evacuate them to the island of Cheju, where a more permanent orphanage is established.

1972—1983 Network television

MASH: Liberal propaganda apotheosis

MASH is a colossal case of a sacred bovine in US culture, almost universally acclaimed, so it may seem foolish, even reckless, to try tilting at it, but that’s what we need to do to peel away the complacency reinforcing the official narrative about these international tragedies. Let us begin by quoting the Wiki:

“ is a 1972–1983 American television series developed by Larry Gelbart, adapted from the 1970 feature film MASH (which was itself based on the 1968 novel MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors, by Richard Hooker). The series, which was produced with 20th Century Fox Television for CBS, follows a team of doctors and support staff stationed at the “4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital” in Uijeongbu, South Korea during the Korean War. The television series is the best-known version of the M*A*S*H works, and one of the highest-rated shows in U.S. television history. M*A*S*H aired weekly on CBS, with most episodes being a half-hour (22 minutes) in length. The series is usually categorized as a situation comedy, though it is also described as a “dark comedy” or a “dramedy” because of the dramatic subject material often presented…”

OK, fine. We get it. This is a much admired and beloved tv series that apparently everyone in America embraces unquestioningly (the list of things Americans embrace without question is long and getting longer by the day). Personally, I think this universal approval may be a case of groupthink, liberal style. Why, let me play the Grinch, once again.

MASH is cowardly. MASH is ostensibly (wink wink) about the Korean war, but it aired during the Vietnam War since the producers quite characteristically wanted to avoid controversy (and risk the ratings). Amiability in the service of the tyranny of conformity, especially when Mammon is involved, is always a strong point with affluent liberals.